In this interview, AZoLifeSciences speaks to researchers from the University of Bath about their latest collaborative research that led to the development of a device that can detect the street drug 'spice'.

What provoked your latest research into the detection of drugs?

Chris: My partner is a Psychiatrist and she commented to me that they have an issue in understanding if the symptoms someone presents with are because of the effects of Spice or other causes, such as a change in medication. I had been working on a different analytical approach that uses fluorescence and she suggested it might work for detecting Spice too.

To be honest, I did not think it would work, but when we did some simple first tests with some example material from my colleagues in Pharmacy and Pharmacology I was really blown away by the sensitivity and accuracy. From there, we expanded our testing and developed a prototype instrument. We have just won a really large grant (£1.3m from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council) to now deliver our solution and to understand how to implement it to support people to the best effect.

Jenny: Chris and I met at a Faculty event to promote research collaboration. When he mentioned the idea of developing a device to detect Spice I could immediately see its potential harm reduction benefits. Drug testing and checking is a developing area.

The lack of quality control for illegal drugs is a real factor in the harm that they cause. Having something that could inform someone’s knowledge on the drugs that they have – in terms of content, strength, and potential risks can inform their decisions around whether they take it and if they do, how much they take.

Spice. Image Credit: Vitalii Vodolazskyi/Shutterstock.com

What is ‘spice’ and what public health problems does this drug cause?

Chris: Spice is a catchall term for a fairly large class of different molecules (>100) that look fairly similar. Initially, they were marketed as ‘synthetic cannabis’ but I think very quickly we realized these molecules do not operate like cannabis, particularly in terms of their side effects.

Spice is almost exclusively used by people who are homeless or in prison. The use in prison in particular can be very high. The reason for the use in these communities is because Spice is cheap, readily available and that is in part because we do not have a rapid test for Spice.

Spice can be incredibly strong and lead to severe health outcomes such as stroke or epileptic seizures. People might be familiar with ‘Spice zombies’ often reported in the news. This is a severe (but not uncommon) reaction to Spice and it is very visual because the users are often homeless, people see it on the streets.

Why is there currently no point-of-care test available that can detect whether someone has recently taken ‘spice’?

Chris: Spice is a very large class of different molecules. The approaches we usually like to use when detecting drugs typically work best when you have a known chemistry presented to you that is the same every time.

With Spice, it could be a huge range of different molecules and we think the picture of the molecules is very regional as well as constantly shifting. The challenge is to have a generic test for a large panel of molecules that is constantly changing.

Can you describe how you developed your spice-detecting device? How does the device work?

Chris: Our approach captures the fluorescence of Spice molecules to create a fingerprint. The fingerprint from Spice is very unique and very strong so it is easy to track. Beyond that, subtle changes in the fingerprint let us identify information about different kinds of Spice, as well as mixtures.

Fluorescence is a nice way to do point-of-care detection because it is well known how to set up small portable instrument to collect fluorescence and they can be very robust and small.

World first on-the-spot test for synthetic drug ‘spice’ developed at University of Bath

What are the benefits of having a quick, portable device for the detection of street drugs?

Chris: We see two sides here. The first is detecting street drugs, to try and tackle the flow of these drugs both within homeless communities and within prisons. This is from the perspective of tackling drug dealing.

Secondly, we are interested in what is called ‘harm reduction’, where we design interventions that can make a positive impact on the health of people who use drugs to try and prevent severe health outcomes like hospitalization. For both of those aims you need highly sensitive and effectively instant detection, so we are confident we have the right technology for the right problem.

Jenny: Current lab analysis of biological samples (usually urine) can take days and require laboratory skills to perform.

We are aiming for a machine that can be operated with a push of a button, so it can be used by a range of people with little training or skills. This means the utility can be wide-reaching and because the machine will be portable, it can be taken to where it is needed.

How will this detecting device also save lives and protect the communities most vulnerable to spice and other street drugs?

Chris: We always think about the scenario where someone presents themselves to A+E or has the first contact with an ambulance crew. The symptoms we see from Spice use can be severe, so someone might not be able to communicate. Users can even be violent and psychotic.

There are a lot of different reasons for some of these symptoms, but knowing it is induced by Spice provides the clinical team with the information to direct the care in the most effective way. Beyond that, we hope we can use the technology within a harm reduction strategy to warn users about particularly potent Spice variants that are circulating, again trying to give people information to keep safe.

Jenny: We know from previous research by others around drug testing and checking that knowledge about drug content informs and reduces risk-taking behavior in most people. Ultimately most people take drugs because they want the positive effects they perceive, they do not want to come to harm.

The device is being developed by a multi-disciplinary team composing of experts in chemistry, AI, pharmacy, and psychology, as well as other areas. What are the benefits of working collaboratively on research projects such as this?

Chris: I think it only works because we have a large multi-disciplinary team. Delivering a solution like this is beyond the ability of a single scientific group, I do not care how big the lab is, you have to bring in the expertise.

For us it is beyond making a nice little box that gives a signal, it is about how we use that nice little box to make a difference so that is where pharmacy and psychology come in.

Beyond that, I would want to say we have partnered not just with different academic groups but also drug testing facilities (MANDRAKE and TICTAC Communications), police forces (Avon and Somerset and Great Manchester), homeless charities (BDP in Bristol and DHI in Bath), a prison (HMP Hull), and the European drug monitoring agency (EMCDDA).

Everyone is pulling in the same direction and because we have this strong team, we have got the best chance of making a difference, rather than a kind of academic curiosity.

Do you believe that with the roll-out of this detection device we can help to stem the flow of street drugs?

Chris: I think it is a deeply complex problem. Detection is part of the answer, but it is only part. I like to think in the UK we are moving towards a more evidence-based drug policy, and our part I think is to both bring in new technologies where they are needed and can be effective but also as a team advocate for people’s health and the support they need.

Jenny: Psychoactive substance use is an inherent part of human behavior and has been for millennia. Although alcohol is by far the most prevalent substance used in society, other substances with different effects and harms are also chosen by some. They are street drugs because of their illegal status.

I do not personally believe that the demand for street drugs can be eliminated, but I do believe that giving information on risk and harm can inform decisions around drug consumption that can help keep people safer.

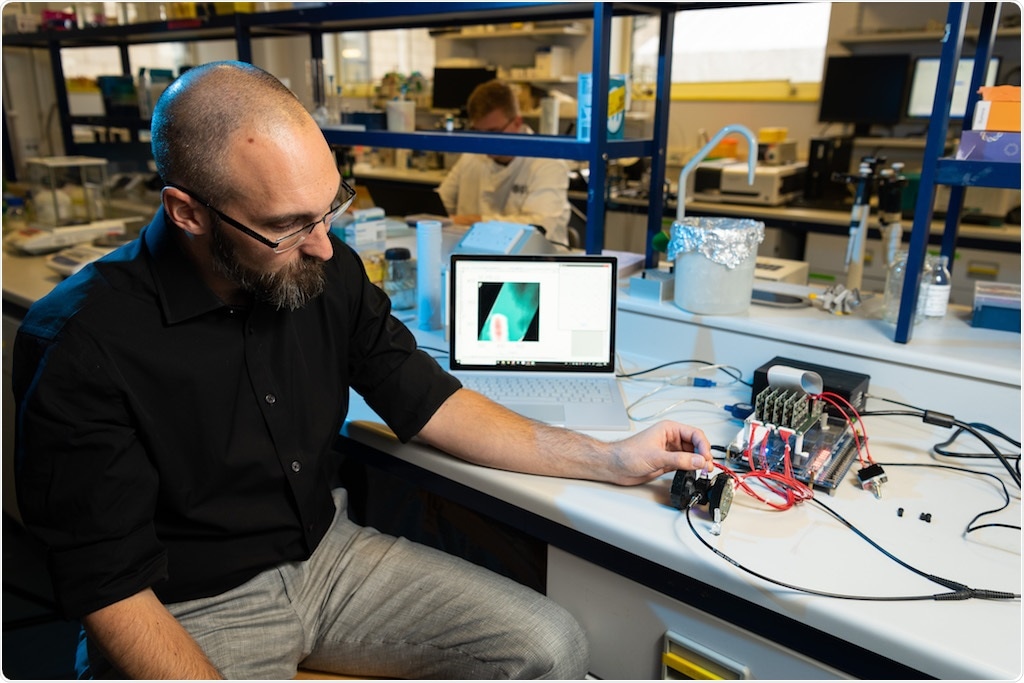

Spice Detector. Image Credit: The University of Bath

When will this detection device be available for use in clinical settings as well as within the police force?

Chris: We have our prototype pretty much there, so we are doing pilot projects with that, particularly with street drugs. The full deployed technology, with all the bells and whistles I would think is a couple of years off.

A large part of that I think is taking the time to understand the users of Spice and how we can use detection technology to best effect. So I do not see it as a technological challenge, more of bringing those different strands together so we genuinely help people.

What are the next steps in your research?

Chris: Something that is a big challenge is detecting Spice embedded in other materials. So for example it is the experience of some prisons that Spice gets soaked onto paper and brought in that way.

We are looking at how we can detect Spice on ‘complex’ matrices like paper, fabric, etc., so a new prototype with wires everywhere, but it is looking promising.

Where can readers find more information?

The original research article that inspired the technology is freely available at https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03037

About Dr. Chris Pudney

Dr. Pudney is an Associate Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Bath, where he runs the Molecular Biophysics Lab.

His lab develops new detection technologies as well as fundamental protein science. He is the Director of BLOC Laboratories Ltd, a University of Bath spin-out company that commercializes technology for detecting and predicting biopharmaceutical stability. He is a recipient of the Royal Society of Chemistry Cornforth Award.

About Dr. Jenny Scott

Dr. Scott is an Associate Professor (senior lecturer) in Pharmacy Practice at the University of Bath where she works on the development of harm reduction interventions.

She is the clinical director of AIM, the Addiction & Mental Health research group at the University of Bath. She works clinically as a prescribing pharmacist within a drug and alcohol treatment service.