Cancer cells can boost tumor development by hijacking enhancer DNA, which is typically utilized when tissues and organs form, according to researchers at the University of Toronto (U of T). The mechanism, known as enhancer reprogramming, occurs in bladder, uterine, breast, and lung cancer and can cause these tumors to develop more quickly in patients.

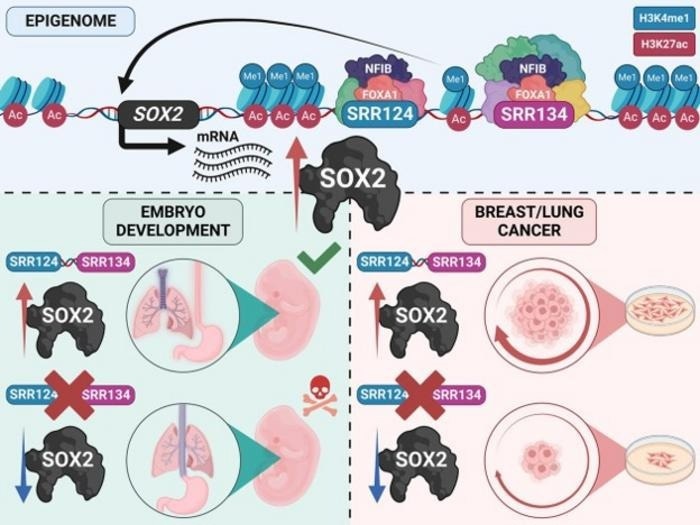

The researchers unravel the exact mechanism of how developmentally active enhancers become repurposed in a tumor context and show the relevance of this repurposing event for cancer. Image Credit: Abatti et al, 2023. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Nucleic Acids Research.

The researchers unravel the exact mechanism of how developmentally active enhancers become repurposed in a tumor context and show the relevance of this repurposing event for cancer. Image Credit: Abatti et al, 2023. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Nucleic Acids Research.

The findings, published in the journal Nucleic Acids Research, also specify the function of various proteins in controlling the enhancer region, which might lead to better therapies for different cancer types.

Living cells, including cancer cells, obey instructions in the genome to turn genes on and off under various situations.

The genome is like a recipe book written in DNA that gives instructions on making all the parts of the body. In each organ, only the recipes relevant to that organ should be followed, whether it’s the instructions for lung, breast or some other tissue. Like flipping pages in a recipe book, the DNA containing the instructions for turning genes on in the lung is open and used in the lung, for example, but closed and ignored in other types of cells.”

Luis Abatti, Study First Author and Computational Biologist, Department of Cell and Systems Biology, University of Toronto

Abatti added, “We know that some cancer cells are opening the wrong pages in the recipe book— ones that contain the SOX2 gene, which can cause tumors to grow uncontrollably. We wanted to find out: how does the gene become expressed in cancer cells?”

The researchers looked through genomic data for enhancer DNA that could activate SOX2 in cancer cells. The enhancer they discovered is active in a variety of patient cancers, indicating that it might be a cancer enhancer active in bladder, uterus, breast, and lung tumors.

Unlike many cancer-causing modifications, this enhancer reprogramming process is triggered by a section of the genome opening when it should be closed, rather than by a mutation induced by DNA damage.

The researchers concluded that the enhancer promotes cancer cell proliferation because when the enhancer was removed from lab-grown cells, the cancer cells formed fewer new tumor colonies.

To figure out why cells contain a DNA region that causes cancer, the researchers created mice without this DNA region and discovered that these mice do not establish a distinct channel for air and food in their throats.

As a result, this potentially harmful cancer-enhancer region in the human genome is believed to influence airway construction as the human body develops. If a cancer cell opens this area, it will generate a tumor that will grow quicker and be more hazardous to the patient.

We also found that two proteins known to have a role in the developing airways, FOXA1 and NFIB, are now regulating SOX2 in breast cancer.”

Jennifer Mitchell, Study Senior Author and Professor, Department of Cell and Systems Biology, University of Toronto

The FOXA1 protein activates the enhancer, while the NFIB protein suppresses it. This suggests that drugs that inhibit FOXA1 or activate NFIB could result in better therapies for bladder, uterine, breast, and lung cancer.

Mitchell concluded, “Now that we know how the SOX2 gene is activated in certain types of cancers, we can look at why this is happening. Why did the cancer cells end up on the wrong page of the genome recipe book?”

Source:

Journal reference:

Abatti, L. E., et al. (2023). Epigenetic reprogramming of a distal developmental enhancer cluster drives SOX2 overexpression in breast and lung adenocarcinoma. Nucleic Acids Research. doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad734