Vascular endothelial cells, a monolayer of endothelial cells, line the total circulatory system from the heart to the smallest capillaries. Therefore, vascular endothelial cells are in direct contact with the cells and components of blood. The vascular endothelium is not considered a simple barrier between tissues and blood; it is also an endocrine organ with many functions.

Image Credit: Caleb Foster/Shutterstock.com

Biology of Endothelial Cells

Vascular endothelial cells are anchored to an 80-nm-thick basal lamina. The endothelial cell and basal lamina represent the vascular intima, making a hemocompatible surface with an approximate combined surface area of three thousand to six thousand square meters in the human body, consisting of 1 to 6 × 1013 endothelial cells.

From the first description of endothelial cells in 1865 until the early 1970s, these monolayers were considered inert barriers to separate blood cells from the surrounding tissues. The luminal membranes of endothelial cells are directly faced with constituents of blood and circulating cells. Glycoprotein basement membranes, which separate the basolateral surfaces from surrounding tissues, are released and anchored to their cell membranes via endothelial cells. Therefore, endothelial cells are polarized cells.

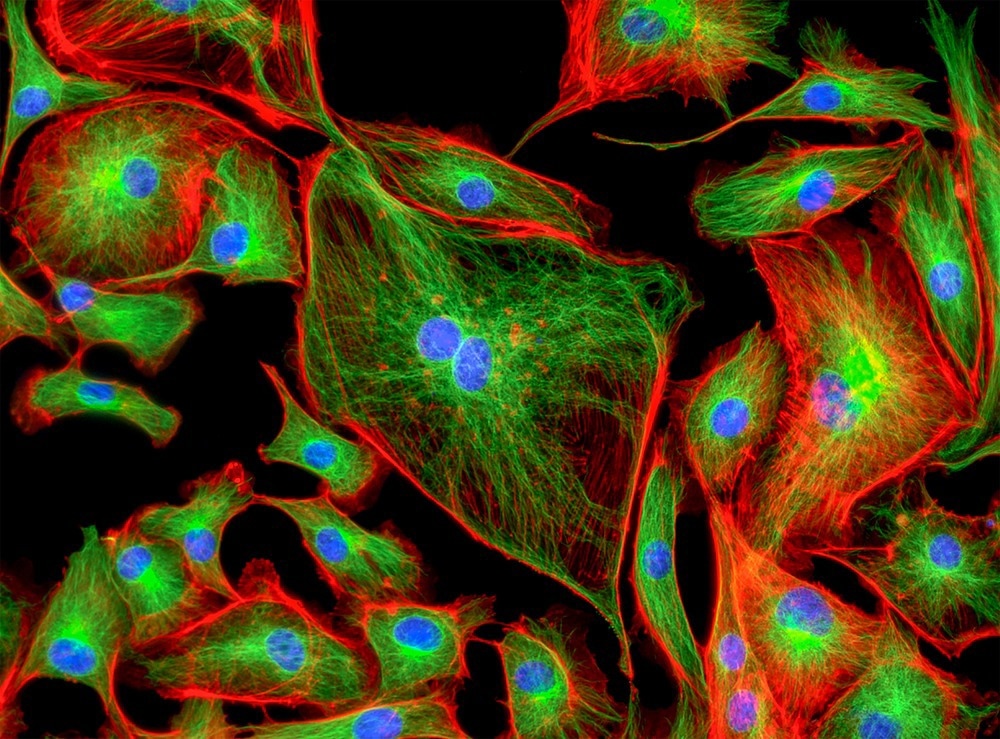

Endothelial cells have variable shapes throughout the vascular tree. However, they are typically thin and somewhat elongated. The dimension of endothelial cells is almost thirty to fifty µm length, ten to thirty µm wide with 0.1–10 µm thickness. To reduce the shear stress produced via the flowing blood, endothelial cells are positioned along the vessel axis in the wall of blood vessels. There is a characteristic cobblestone pattern in vitro endothelial cell monolayers.

A membrane-cytoskeletal protein called vinculin is found in focal adhesion plaque that is present in cell-matrix junctions and cell-cell via connecting integrin adhesion components to the cytoskeleton actin. Owing to the heterogeneity of the vascular system, it is difficult to consider the endothelial cells, which play an important role in vascular performance, as inert cell layers.

Image Credit: Shot4Sell/Shutterstock.com

Role of Endothelial Cells

Vessels with a big diameter, such as arteries, arterioles, veins, and venules, connect the blood from the heart to tissues and organs. This is typically done, under physiological conditions, with no great waste of cells or blood fluid across the endothelial cell layer. Although there is a great difference and variability in blood pressure, endothelial cells maintain low permeability.

There is variability in the common vascular framework that represents the hierarchical system of the heart, arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, veins, and heart. This succession of types of vessels has variations in specific vascular networks. It is organized in arterioles, capillaries, and arterioles, followed by capillaries, venules, and veins in the kidney glomeruli.

The vascular system is complex; these are a few examples that reflect the diversity of processes that endothelium faces under normal conditions. Exaggeration of this complexity is observed under pathophysiological conditions. Endothelial cells have several functions which are special to their locations, and they show substantial phenotypic heterogeneity throughout the vascular bed.

Endothelial cells can powerfully control the vascular constriction/relaxation degree, the extravasation of solutes, hormones, macromolecules, and fluid, as well as that of blood cells and platelets. Additionally, endothelial cells have an active role in the intermediate vascular layer cells' quelling to eschew the outgrowing into the tunica intima layer, which can disturb normal vascular function.

Endothelial cells help regulate vascular constriction and relaxation and the leakage of fluid, solutes, hormones, and macromolecules, as well as that of blood cells and platelets. The prostacyclin discovery and its synthesis in endothelial cells have underscored the importance of endothelium as a pivotal factor in the homeostasis of different pathophysiological mechanisms.

The endothelium does not have a passive role, but it is a dynamic organ. It regulates its external environment and responds to external stress. The endothelium is considered to be an endocrine and active metabolic organ. Endothelial cells supply oxygen to tissues via synthesis and releasing of contracting and relaxing factors that modulate blood flow rate.

Continue Reading: Diversity in Cellular Cardiac Tissue

Sources:

- Krüger-Genge, A., Blocki, A., Franke, R. P., & Jung, F. (2019). Vascular endothelial cell biology: an update. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(18), 4411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20184411

- Garland, C. J., Hiley, C. R., & Dora, K. A. (2011). EDHF: spreading the influence of the endothelium. British journal of pharmacology, 164(3), 839-852. DOI: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01148.x

- Tailor, A., Cooper, D., & Granger, D. N. (2005). Platelet–vessel wall interactions in the microcirculation. Microcirculation, 12(3), 275-285. DOI: 10.1080/10739680590925691

- Krüger, A., Mrowietz, C., Lendlein, A., & Jung, F. (2013). Interaction of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with platelets in vitro: Influence of platelet concentration and reactivity. Clinical hemorheology and microcirculation, 55(1), 111-120. DOI: 10.3233/CH-131695

- Monahan‐Earley, R., Dvorak, A. M., & Aird, W. C. (2013). Evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and endothelium. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis, 11, 46-66. DOI: 10.1111/jth.12253

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 25, 2023