Serendipity is defined as an unexpected discovery due to a chance encounter (not intentionally looking for it), sagacity (wisdom and scientific knowledge required to understand the chance observation), and a prepared mind (ability to visualize the potential in the accidental observation and constructively utilizing it), which often leads to a fruitful outcome. Serendipitous discoveries, such as penicillin, radioactivity, X-rays, vulcanized rubber, or the microwave oven were not solely chance discoveries; they required a curious, open, and flexible mind.1

For example, Henri Becquerel noticed spots on photographic plates that were kept near uranium salts. Someone without a scientific bent of mind may have discarded the plates.

Becquerel’s curiosity about this interesting observation prompted him to perform further experiments and determine the source as uranium, eventually leading to the discovery of radioactivity. This showed that it was not only Becquerel’s chance observation but also the relevant scientific knowledge which encouraged further evaluations and an explanation for the accidental discovery.2

Image Credit: liliya Vantsura/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: liliya Vantsura/Shutterstock.com

Key Concepts of Serendipity in Science

What is Serendipity in Science?

Serendipity is an unexpected albeit fortunate discovery that happens when we have an open mind to new experiences. Serendipitous discoveries are not just a product of luck but involve an awareness that enables us to recognize and seize opportunities when encountered. Curiosity can transform a random observation into a remarkable discovery as it affects our perception and response to an unexpected event. A curious mind asks questions, pursues solutions, and engages meaningfully with the world around them.3

For example, Dr. Rosenberg’s team’s curious nature led to the discovery of cisplatin. When they applied electric current using inert platinum electrodes to E. coli, they found some cells died, whereas others grew longer. Further investigation revealed that the cells grew longer due to a chemical produced by the reaction between the platinum electrodes and the nutrient solution.

The chemical was cisplatin. The observation of elongated cells and their inability to divide prompted them to test cisplatin as an anticancer agent on mice tumors, and they found it to be effective. Cisplatin was approved as a chemotherapy drug and is used even today.4

Serendipitous discoveries occur because of a well-prepared mind capable of recognizing an accidental event and constructively using it. For example, when Dr. Richard Blumberg’s postdoctoral student was frustrated due to a failed negative control experiment in a human intestinal cell line, Dr. Blumberg immediately recognized that the control antibody was binding the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) on the cell surface.

This thought was triggered due to his work on major histocompatibility complex class 1 molecules located on the cell surface. However, FcRn was known to be found only in neonatal rodents and not in adult rodents or humans. Further experiments revealed that FcRn was found in many cells in humans during adulthood.5

Why Does Serendipity Matter?

Serendipity is crucial for innovation. The ability to recognize desirable opportunities and make connections between apparently unconnected situations and things during a chance encounter fosters innovative ideas as one becomes open-minded about the findings. Serendipity is complementary to other types of exploration, including search, experiment, and plan, which provide unanticipated chances to identify new information and take an innovative idea ahead.6

Creativity is the ability to generate novel views, concepts, questions, or solutions, the willingness to explore ideas, and observe already existing ideas in a new light. Thus, creativity requires flexible thinking and letting go of traditional ways. Flexibility encourages the willingness to explore unfamiliar situations without the fear of failure, increasing the chances of serendipitous discoveries.3

The Role of Natural Products in Modern Drug Discovery

Famous Examples of Serendipitous Discoveries

Penicillin

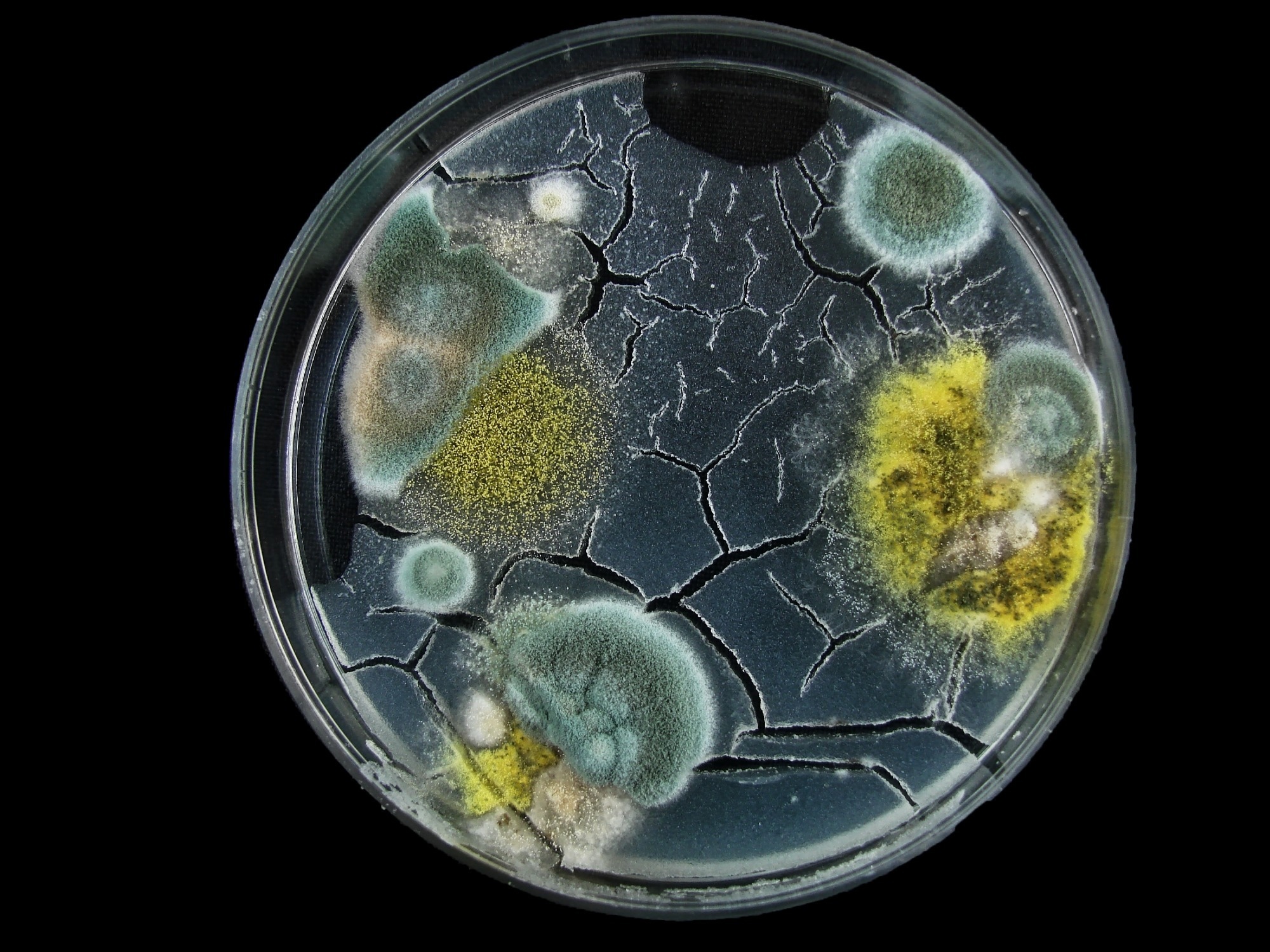

When Alexander Fleming was investigating Staphylococcus, he noticed a blue-green mold growing on the petri dish that was mistakenly left open, and it had killed the neighboring bacteria. His curiosity prompted him to isolate the mold.

He concluded that the fungus killing the bacteria belonged to the genus Penicillium and was secreting a bactericidal agent, which he named penicillin. Ernst Chain and Howard Florey purified, characterized, and widely publicized penicillin as the nontoxic antibiotic capable of killing bacteria.7

X-rays

While working with the cathode ray tube, Wilhelm Röntgen noticed that an incandescent green light escaped the tube covered in black paper and illuminated a fluorescent screen. He held his hand before the tube, and his bones were visible on the screen.

The first X-ray images were produced when the tube was replaced with a photographic plate. This serendipitous discovery has become an indispensable diagnostic tool for identifying pneumonia, broken bones, tumors, and heart failure.8

CRISPR-Cas9

Francisco Mojica suggested that CRISPR is a part of the adaptive immune system of bacteria as it contains repeat sequences separated by spacers that match certain sections of bacteriophage genomes. Horvath and Barrangou showed that lactic acid bacteria became resistant to bacteriophages when sequences from bacteriophage genomes were incorporated into bacteria. The Cas9 protein from Streptococcus pyrogenes was essential for phage resistance and subsequent degradation.

This natural phenomenon was harnessed for genome editing by the groups of Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, who unveiled the CRISPR-Cas9 system’s mechanism of action.9,10

Velcro and Other Innovations

George de Mestral noticed that the burr seeds from the burdock plant stuck to his dog’s fur and his clothes. Mestral’s curiosity made him examine the burr seeds under the microscope. He noticed the seeds had many hook-like structures, which would cling to anything with a loop, such as fabric, hair, or fur.

He recreated this natural adhesiveness using strips of fabric, one with hooks and the other with loops. Today, Velcro has become an important part of our everyday lives; it is used from camping equipment to blood pressure cuffs and toys.11

Percy Spencer observed that the chocolate in his pocket had melted while he was making radar equipment. He suspected the cause was the microwaves emanating from the magnetron, a radar component. He tested his hypothesis with corn kernels, which popped one after another. The initial microwave model was publicly available in 1947.7

Connecting curiosity -- tales of science serendipity | Laura Green | TEDxWellington

Serendipity and Modern Science

The Role of Open-Ended Research

Exploratory research examines undefined problems. It aims to better understand the problem but does not provide definitive solutions.

A crucial aspect of exploratory research is to be open-minded, flexible, and adaptive to change the research direction as more data is obtained. One must learn to embrace failures as many serendipitous discoveries result from failed experiments as seen in the case of penicillin.12

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

An observation made in isolation cannot recognize every opportunity. Collaborating with people from different subject areas can boost serendipitous discoveries. Researchers must present their observations to a diverse audience, attend conferences, and have informal discussions outside their discipline to gather different opinions and be open to suggestions and feedback, which can be rewarding and lead to unexpected discoveries.

For example, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna collaborated at a conference in Puerto Rico, which led to the discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing tool.13,14

The Role of Technology

The vast datasets generated from observation through instruments, such as microscopes and experiments, make it challenging for researchers to determine patterns or relationships that can lead to new hypotheses.

Although the traditional literature review methods are useful and depend on pre-existing knowledge, unanticipated associations can go unnoticed. AI is a powerful tool that can analyze huge datasets to unveil these hidden associations.

Natural language processing can analyze the literature and identify important concepts, inconsistencies, and relationships to determine the gap in the literature. Training AI on existing scientific knowledge helps in the identification of established theories. This prompts researchers to explore novel avenues in research, investigate the reason behind the discrepancies in literature, and propose novel hypotheses.15

What Role does Fermentation Play in the Pharmaceutical Industry?

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

- Defining clear goals provides a framework where creativity can thrive. However, one should be flexible and adapt to emerging novel ideas. Flexibility permits the utilization of serendipitous discoveries, which usually result from creativity, and ensures innovation is not suppressed by a rigid framework. Collaboration drives the harmonious coexistence of structure and creativity. It is crucial to have open discussions and obtain different perspectives, which aid in converting spontaneous raw ideas into structured innovations.3

- The ethical requirements of clinical research may be a stumbling block for researchers who make unexpected significant observations. Unlike Fleming who tested and manipulated mold to identify its properties, one cannot use humans as a subject to confirm an unexpected yet noteworthy observation as humans have their desires, goals, and values. There are seven criteria for conducting an ethical clinical study when pursuing a chance observation:

- The research must add value either as improved health or enhanced knowledge.

- The research design must be scientifically valid to ensure the obtained outcomes answer a relevant question.

- Fair participant selection that addresses the goals of the study.

- The benefits must either outweigh the risks or justify the estimated risks.

- An independent review of the study to assess whether the study is valid, valuable, and does not harm the patients.

- A voluntary, informed consent must be obtained from the participants. Any proposed changes in the study design must be discussed with the participants, and they should be free to withdraw their participation without penalty.

- The participants' privacy must be of utmost importance.16

Conclusion

Serendipity plays an important role in science and is responsible for many important discoveries. A deliberate change in the procedure, an error, or an oversight can alter the experimental outcome and lead to a serendipitous discovery. However, chance is not solely responsible for accidental discoveries.

Other factors, including curiosity, openness to accept different results, relevant scientific knowledge, and the ability to see and pursue further investigations on unexpected outcomes plays a crucial role.

To foster innovation, we need to create an environment that encourages discussions and helps connect with people from different walks of life without being judged; curiosity and openness to welcome new experiences; and continuous pursuit to improve scientific knowledge that will enable serendipity.

References

- Ricciardi CR. (2005). Serendipity in research and practice: Nurturing imagination and inquiry. Journal of Pediatric Health Care;19(1):A18–9. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0891524504003785

- Understanding Science 101. Exploration and Discovery. [Online] Available at: https://undsci.berkeley.edu/understanding-science-101/how-science-works/exploration-and-discovery/. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Anand K. The serendipity mindset: understanding the concept. Innovio. [Online] Available at: https://innovioblog.in/the-serendipity-mindset-understanding-the-concept. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Crampton L. (2023). Serendipity: the role of chance in scientific discoveries. Owlcation. Available at: https://owlcation.com/stem/Serendipity-The-Role-of-Chance-in-Making-Scientific-Discoveries. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2015). Chance and prepared minds lead from lab to new drug development. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/news/archive/2015/prepared-minds-lead-lab-new-drug-development. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Calderon ACZ. (2022). What is the role of serendipity in innovation? [Online] Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-role-serendipity-innovation-andrea-zuniga. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Shackle S. (2015). Science and serendipity: famous accidental discoveries. [Online] Available at: https://newhumanist.org.uk/4852/science-and-serendipity-famous-accidental-discoveries, [Accessed on 4 December 2024].

- History of medicine: Dr. Roentgen’s Accidental X-rays. Columbia Surgery. Available at: https://columbiasurgery.org/news/2015/09/17/history-medicine-dr-roentgen-s-accidental-x-rays. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Lander ES. (2016). The heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 164(1):18-28.

- CRISPR/Cas9 - how gene scissors work. Max Perutz Labs. [Online] Available at: https://www.maxperutzlabs.ac.at/research/key-discoveries/crispr/cas9-how-gene-scissors-work. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- The velcro story. (2020). Paperflite. [Online] Available at: http://www.paperflite.com/blogs/velcro-story. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Palat LN. (2024). The psychology of serendipity: does luck favour the curious ones? [Online] Available at: https://gulfnews.com/friday/wellbeing/the-psychology-of-serendipity-does-luck-favour-the-curious-ones-1.1727430676067. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Herbert R. (2022). How to enhance your chances of serendipitous research discoveries. Times Higher Education. [Online] Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/how-enhance-your-chances-serendipitous-research-discoveries. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Lyall C. (2020). Facilitating serendipity for interdisciplinary research. Integration and Implementation Insights. [Online] Available at: https://i2insights.org/2020/01/21/serendipity-for-interdisciplinarity/. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- The spark of serendipity: how AI is revolutionizing hypothesis generation in science Glueball Technologies. [Online] Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/spark-serendipity-how-ai-revolutionizing-hypothesis-generation-rhxce. [Accessed on: 4 December 2024].

- Copeland SM. (2015). The case of the triggered memory: serendipitous discovery and the ethics of clinical research. Dalhousie University. [Doctoral Thesis]. Available at : Copeland-Samantha-PhD-PHIL-Sept-2015.pdf

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 10, 2024