Exploring the history and functionality of microplate handlers, the article highlights their evolution from the 1950s to becoming indispensable to genetic research today. For insights into the advancements and potential of microplate handlers in scientific research, continue reading.

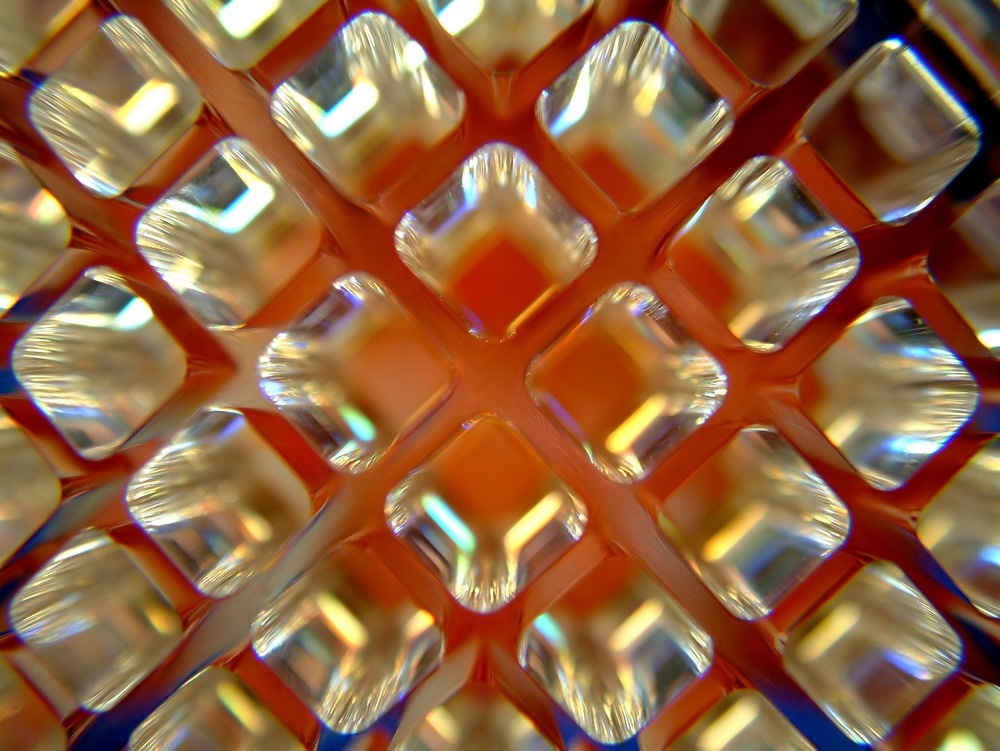

Image Credit: Caleb Foster/Shutterstock.com

Microplate History

The microplate or well plate was created in 1951 by Dr Gyula Takátsy, a Hungarian physician and scientist who created 6 rows of 12 ‘wells’ out of poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). This invention was the result of a laboratory equipment shortage that came after an influenza epidemic in the early 1950’s.

Along with the development of microplates, several other laboratory techniques and tools were also created, including a replacement for pipettes through small platinum spiral loops for multiple serial dilutions in microplates.[1]

Microplates have evolved over the past 60 years and are now essential laboratory equipment used today.[2] Interestingly, microplates used to vary in size and dimension in the early days of the invention; however, they currently conform to the Society of Biomolecular Sciences standards, which ensures all handlers can process almost any plate.[3]

Laboratory automation progress in microplate manufacturing started in 1980’s, and was pioneered by Dr. Rod Markin, focusing on integrating off-the-shelf testing components with automation software to carry out laboratory tasks. In the early days, automated microplate handling was only used by large companies that could afford the high expenditure as a result of the significant volume that provided a profit.[4]

How Do Microplate Handlers Work?

Microplate handlers consist of specialized robotic devices that can transfer microtiter plates in a 3D space from one place within a workflow to another, such as from solvent addition via liquid handling to heating, shaking or incubation.[5]

The use of a handler can confirm the presence of a specific protein, as well as making its collection easier, more accurate, and repeatable.[6]

Microplate Handlers in Genetic Research

Liquid-handling automation has been adopted for genomic applications to increase efficiency in sequencing workflow as well as for its cost-effective benefit.[7]

Applying genomic analysis for cancer diagnostics in the UK was investigated in a study, revealing that an entire manual process for next generation sequencing (NGS) results can have a six-day turnaround time from receiving a request for molecular diagnostics to producing a genomics report. This can seem unsustainable for scaling operations and sequencing up to a dozen samples simultaneously.[7]

While some parts of the process have already been automated, including nucleic acid extraction, preparing reagents and plates for extraction still predominantly requires manual labor. Manual processing can be repetitive and error-prone, resulting in significant time consumption and cost inefficiencies.[7]

Liquid handling automation can improve high-throughput performance in laboratories in a cost-effective fashion. Interestingly, a cost-analysis breakdown for genome sequencing has demonstrated 15% of the total cost is related to laboratory personnel in a conventional clinical laboratory.[7]

Liquid handling robots that are available on the market have the capacity to meet a range of automation requirements for NGS, including Tecan’s Freedom EVO NGS workstation, which is a fully-fledged robotic workstation that combines liquid handling with other tasks.[7]

Within genetics and genomics laboratories, a significant concern includes the risk of contamination, which may be resolved with liquid-handling robotics. This type of automation can have washing modules that are able to perform cleaning up of the robot head after each use, as well as the potential option of adding a microplate washer for well plates.[7]

Additionally, another use of robotics in genetics laboratories is for precision and accuracy, with the Hamilton Microlab STAR detecting liquid levels dispensed, while other workstations, including Tecan and Eppendorf consist of integrated sensors for contact-free liquid level detection that ensures precision.[7]

Industry developments

Recently released microplate handlers include BioStack3 LS Microplate Stacker and MiniSeal Plus Heat Sealer. BioStack3 LS Microplate Stacker provides fast plate transfer, as well as being compatible with the company’s other systems such as microplate washers, dispensers and pipetting and detecting systems. MiniSeal Plus Heat Sealer by Porvair Sciences also ensures high integrity in the sealing of deep wells and even irregularly shaped microplates.[5]

Microplate handlers, including GE’s Biacore 8K SPR biosensor system have identified a viral polymerase, including fragments of NS5B, which is involved in the replication of hepatitis C at low millimolar affinities. Automated robotics can aid in the advancement of genetics and genomics, with these tools assisting in detecting low-affinity proteins.[6]

With the annual global market for microplates approaching $500 million worldwide and being dominated by several companies, both microplates and microplate handlers hold significant potential for advancing analysis for a range of different fields, including genetics.[8,7]

Conclusion

Microplate handlers for genetic research may aid in advancing the scientific field, with handlers increasing the speed of laboratory results, such as confirming the presence of specific proteins. Microplate handlers can also aid with the accuracy, repeatability of results and efficiency of sequencing workflows.[6,7]

As a whole, lab automation, including microplate handlers can advance the manual process of NGS as well as genetic research as a whole, which can improve the turnaround time for results for molecular diagnostics for healthcare systems that may move to sequencing several samples at a time. This may improve the efficiency of diagnostics and ensure patients are provided with earlier diagnoses and better treatment management.[7]

Sources:

- Jaquith K. The history of the microplate: Microtitrator: Dr. Gyula Takatsy. WellPlate.com. August 11, 2018. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://www.wellplate.com/the-history-of-the-microplate/.

- Buie J. Evolution of microplate technology. Lab Manager. January 5, 2010. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.labmanager.com/evolution-of-microplate-technology-19972.

- DePalma A, DePalma A, Profile. F. Product focus: Microplate handlers. Lab Manager. February 26, 2011. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.labmanager.com/microplate-handlers-robotically-connecting-microplate-operations-18868.

- History of microplate handling. Hudson Robotics. November 14, 2018. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://hudsonrobotics.com/history-of-microplate-handling/.

- Microplate handlers. Lab Manager. August 9, 2012. Accessed January 20, 2024.

- May M, May M, Profile. F. Microplate handlers: Plate handling for protein research. Lab Manager. December 10, 2017. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.labmanager.com/microplate-handlers-plate-handling-for-protein-research-2618.

- Tegally H, San JE, Giandhari J, de Oliveira T. Unlocking the efficiency of genomics laboratories with robotic liquid-handling. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12864-020-07137-1

- Banks P. The microplate market past, present and future. Drug Discovery World (DDW). April 15, 2009. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.ddw-online.com/the-microplate-market-past-present-and-future-1127-200904/.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 30, 2024