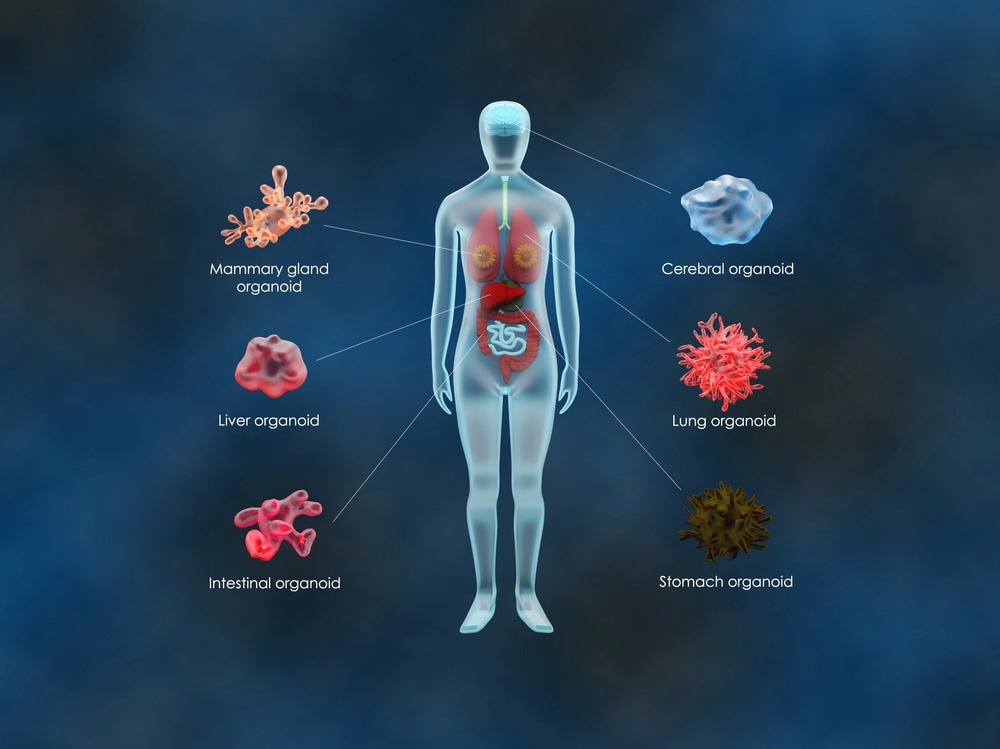

1999 was the year of the Y2K scare, when Euros first entered the market and when the Space Shuttle Discovery became the very first vessel to dock with the International Space Station. It was a memorable year for science and culture. It was also the year cancer ‘organoids’ were developed to allow scientists to study a patient’s tumors in fine-grain detail.

Image Credit: Meletios Verras/Shutterstock.com

Worldwide Cancer Research funded a project that ended with scientists being able to grow mini-tumors (organoids) from a patient’s own cancer cells. This allowed scientists to study the complex biology of tumors up close, gaining a deeper understanding of tumors while facilitating the selection of the most appropriate treatment for the individual - the beginnings of personalized medicine.

What are organoids?

Organoids are 3D structures that are grown from stem cells. Organoids are essentially mini-organs that possess all the cells that would be found in an organ within the body, and it develops in a way that mirrors the architectural and functional characteristics of the organ if it were to have grown in the body. To grow an organoid, a biopsy is taken from a patient from tissue that is desired to be recreated.

This method allows scientists to look closely at cancer, specifically cancer inflicting a particular individual. It lets them study how cancer will react to different treatments, helping them decide the best treatment plan for the patient. Without this model, treatment can go down a trial-and-error path, which can end in wasted time trialing an ineffective treatment, time that many patients with cancer simply do not have.

Organoids are not just useful for studying cancer; they can be developed from a range of cell types to study a plethora of diseases, including genetic, infectious, and malignant diseases. Organoids can be developed from any adult stem cell, allowing diseased tissue to be compared with healthy tissue from a given individual. Additionally, with the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, the genetic makeup of organoids can be manipulated to create models of human disease. Studies have used patient-derived organoids for drug development and to establish personalized medicine for a number of diseases, although it arguably has the most value for cancer and cystic fibrosis.

Opening the door to personalized medicine

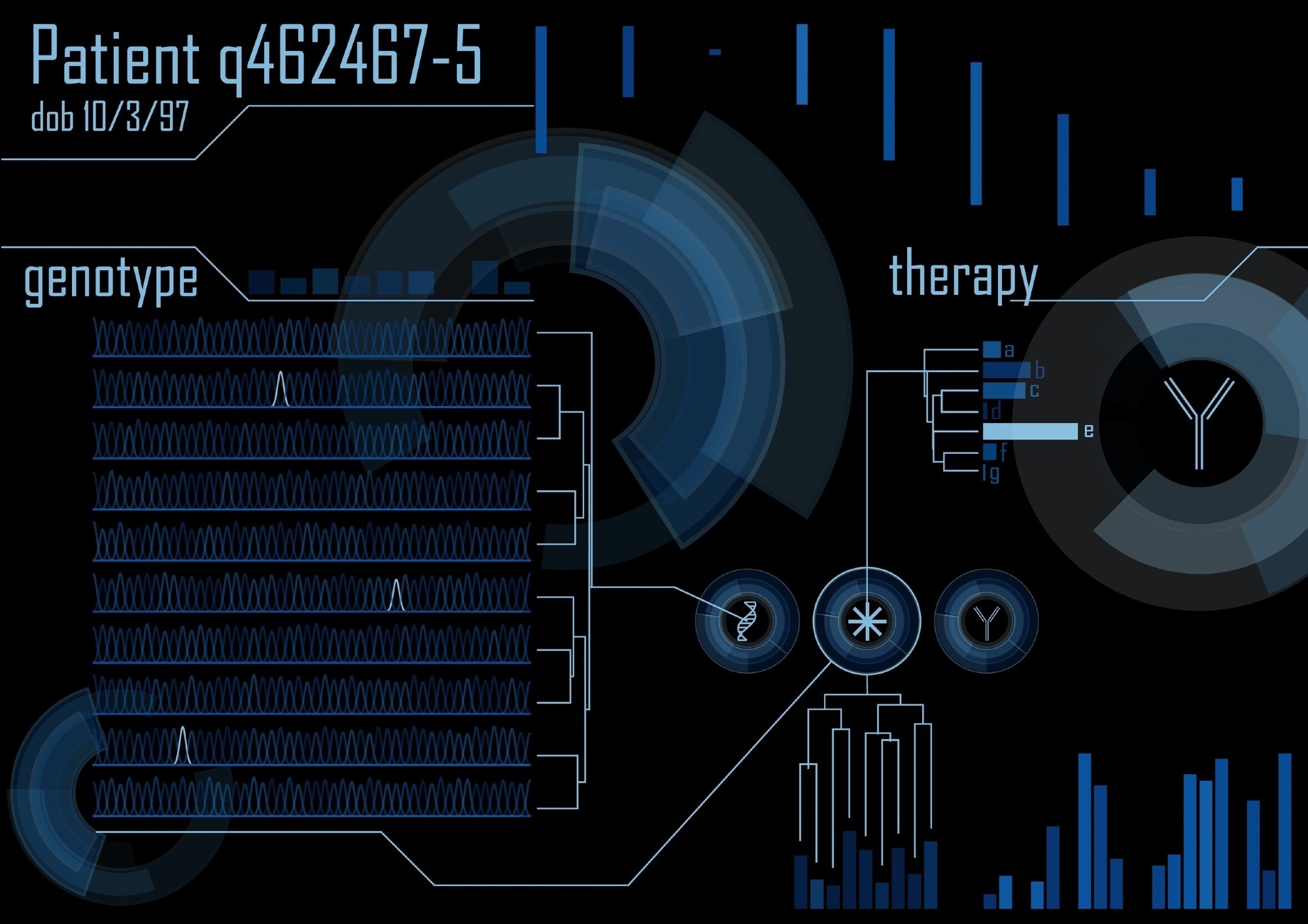

Organoids provide an ideal model for investigating the function of genes by editing the genome with CRISPR-Cas9 technology. This system enables scientists to link genotype to phenotype, thus revealing genes causative of disease. With this knowledge, personalized medicine becomes a possibility.

Organoids are also useful for screening treatments. For example, cancer potentially derives the most benefit from personalized medicine due to the variability in response that patients have to traditional therapy (e.g., chemotherapy). Organoids derived from patient cells can be exposed to thousands of drugs to identify the most effective at killing cancer. This is particularly important for understanding how to effectively manage harder-to-treat and late-stage cancer. This model prevents wasting time on ineffective medicine by rapidly discovering which treatment option suits the individual best.

A recent study has shown that organoids derived from cells of patients with ovarian cancer can be used for drug sensitivity assays, thus showing how organoids have the potential to support personalized medicine. Clinical trials are currently underway to establish how organoids can be used in clinical practice, to bring this methodology from the lab to the clinic (available to patients).

A large prospective study is currently in progress, Organotreat-01, that is being led by scientists at the Gustave Roussy Institute to examine the usefulness of organoids in guiding the treatment decisions for patients with digestive cancer. The study is estimated to be completed in 2027. Other studies are also in progress examining the efficacy of the organoid model in selecting the most appropriate chemotherapy regimens for patients with lung and pancreatic cancer.

Additionally, as discussed above, personalized medicine has great promise for cystic fibrosis. The use of organoids in modeling cystic fibrosis is probably the best example of organoids modeling human genetic disease. Studies with organoids derived from the rectum of patients with cystic fibrosis have revealed the function of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene (inactivations of which underly the disease).

Image Credit: grinimal/Shutterstock.com

Future directions

The use of organoids is still in its infancy, and its full potential in developing personalized medicine is far from being met. Currently, important studies are underway that will likely establish organoid models for cancer treatment.

By the end of the decade, these may be available in clinics to direct treatment plans for patients with a variety of cancer. In addition, other diseases, particularly genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and infectious diseases, also stand to benefit from organoid models that will open the door to personalized medicine.

Sources:

- Li, Y. et al. (2020) “Organoid based personalized medicine: From bench to bedside,” Cell Regeneration, 9(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13619-020-00059-z.

- Our impact: Building mini-tumour organoids to help personalise cancer treatment [online]. Worldwide Cancer Research. Available at: www.worldwidecancerresearch.org/.../ (Last accessed December 2022)

- Perkhofer, L. et al. (2018) “Importance of organoids for Personalized Medicine,” Personalized Medicine, 15(6), pp. 461–465. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2217/pme-2018-0071.

- Prospective Multicenter Study Evaluating Feasibility and Efficacy of Tumor Organoid-based Precision Medicine in Patients With Advanced Refractory Cancers (ORGANOTREAT) [online]. US National Library of Medicine. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05267912 (Last accessed December 2022)

Last Updated: Jan 30, 2023