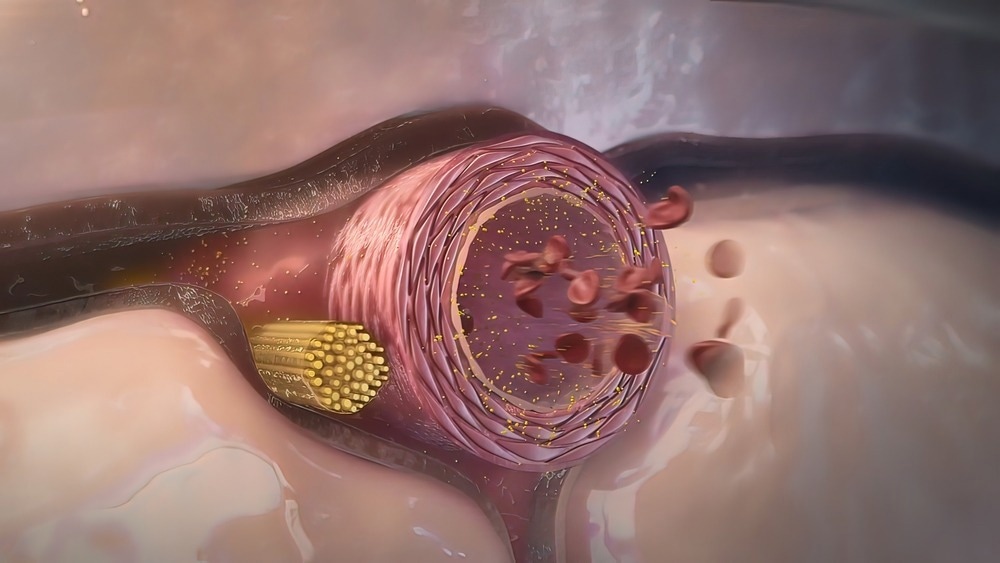

A vesicant is an agent that can cause blistering, tissue sloughing (peeling), or necrosis when it escapes from the targeted vascular pathway and moves into the surrounding tissue. It is distinct from an irritant, defined as an agent that can produce pain or discomfort in the internal lumen of the vein. The key distinction between a vesicant and an irritant is that damage induced by a vesicant occurs in the subcutaneous tissue outside of the vein; in the case of irritants, the damage occurs inside the wall of the vein.

Image Credit: picmedical/Shutterstock.com

Vesicants that cause tissue damage may do so in two mutually exclusive ways. They typically cause blistering and tissue sloughing or necrosis. Surgical intervention is not always necessary when the damage caused is attributed to tissue sloughing or blistering. In these cases, the area may heal over time and not result in permanent tissue destruction. Necrosis, however, requires surgical debridement, which may include skin grafting for complete healing.

The site at which vesicants produce their effect is at, or near, the point of fluid escape from the vein; this may be at the point of vein puncture or the location of a catheter tip, for both. Irritants, by contrast, cause vein inflammation, otherwise known as thrombophlebitis. The damage, therefore, is restricted to the interior of the vein lumen. This inflammatory process can subsequently produce severe edema. However, no fluid leakage is associated with this process, and no leaking occurs into the subcutaneous tissue.

What are some examples of vesicants, and what is their mode of action?

Vesicants are cytotoxic alkylating compounds. A classic example of a vesicant is mustard or mustard gas. However, blistering agents include sulfur mustard, nitrogen mustard, lewisite, and phosgene oxime. Vesicants inhibit cell division and decrease tissue respiration, leading to cell death.

Vesicants in Warfare

While vesicants are used in the clinical setting in the context of treatment, they have been used in chemical warfare. Conjunctivitis can occur after one hour at a concentration of vesicant that cannot be detected by smell. Mild exposure results in tearing under the experience of high grit between 4 and 12 hours. Severe damage to the eye may occur within two hours after heavy exposure. A specific type of vesicant, such as lewisite and dichloroarsines, can cause cornea scarring at the point of contact.

Skin damage may not be immediately seen as sometimes initial effects may be painless until the deepest skin layers are reached, and blisters appear. Diagnosis is made when fluid-filled skin blisters arise and are recognized. Skin burning and itching may occur during a latent period of between one and 12 hours. Redness appears on exposed skin between 2 and 48 hours after exposure. Burning may be exacerbated in the groin and genitalia due to increased moisture and ambient temperatures.

The vesicant still presents on a contaminated patient can pose a biohazard to other individuals who may come into contact. The severity of the blister formation differs depending on the vesicant agent the individual is exposed to. For example, lewisite and dichloroarsines can cause more opaque blisters relative to mustard gas. They are also responsible for causing deeper injury to connective tissue, which extends as far as the muscle and vasculature, and the extent of inflammation is more severe. In most cases, healing and resorption of uninfected blisters can occur between 1 and 3 weeks for all vesicants. To minimize chances of infection and scarring, broken blisters need to be protected.

How Do Vesicants Exert Their Damage?

Typically, exposure to vesicants results because of extravasation. Extravasation is the leakage of intravenously infused and potentially damaging drugs into the extravascular tissue around the site at which the drugs are infused. This leakage occurs through delicate veins in the elderly or with previous venipuncture access. If the leakage does not cause any adverse event, it is referred to as infiltration. An extra visitation is an adverse event related to a form of therapy related to the identity of the medication, the degree of exposure, and the location at which this occurs.

Intravenous infusion is the principal mode of administration in several therapeutic approaches, most notably for administering anti-cancer drugs. Chemotherapy administration carries extra visitation as a safety concern, which in the context of chemotherapy, is defined as the accidental infiltration of chemotherapy drugs into the subcutaneous tissue at the site of injection, which can subsequently result in necrosis.

How Do Vesicants Fit in The Context of Drug Administration?

Vesicants are one of 5 categories that intravenously administer drugs fall into. The remaining four are:

- Exfoliants: Drugs that can cause inflammation and sloughing of the skin without causing tissue necrosis. These drugs may cause superficial tissue injury, blisters, peeling skin, or desquamation.

- Irritants: Drugs that can cause inflammation, pain, or irritation at the site where extravasation occurs; this does not cause blistering. Irritants also may cause a burning sensation in the vein during administration.

- Inflammatants: Drugs that cause mild to moderate inflammation and redness of the skin (erythema). A flower reaction at the extravasation site may also occur.

- Neutrals: Jokes that do not cause inflammation or any damage after extravasation occurs

Vesicants may also be subclassified into either drug that finds DNA on drugs that do not bind DNA. DNA-binding drugs produce tissue damage with increasing severity.

Factors That Affect the Extent of Vesicant Damage

Vesicants with high vasoconstrictive potential can result in an increased probability of tissue necrosis due to severe vasoconstriction of capillary smooth muscles, which subsequently reduces blood flow. Vesicants that remain in extravasation tissue for a long period lead to a Repetitive cycle of continuous injury to cells. Conversely, vesicants that are easily metabolized and are not retained at the site of administration do not bind to DNA, which accounts for their easy metabolism.

Treating Damage Caused by Vesicants

Elevation of the limb in the context of clinical extravasation is thought to aid in the reabsorption of the infiltrate or extravasated vesicant by decreasing the hydrostatic pressure in the capillary. A sterile dressing is also placed over the area of extravasation and is regularly assessed and documented. Thermal application may also aid in the treatment of pain and inflammation.

Local cooling aids in vasoconstriction, limiting the drug's dispersion. Cold application is recommended for the extravasation of vesicants which are DNA binding. Conversely, local warming therapy using dry heat may be used because it enhances vasodilation, thereby increasing the vesicant's dispersion and decreasing the drug's accumulation in the local tissue. This type of thermal application is recommended for non-DNA binding vesicants.

To prevent extravasation of vesicant drugs, it is recommended that the cannula is not inserted in the joints as it is difficult to secure in this position, and there is a high risk of damage to the neurons and tendons if extra visitation is to occur. Moreover, even when an existing intravenous route is present, clinicians are advised to secure a new route when administering vesicant drugs to minimize extravasation.

Sources:

- Kim JT, Park JY, Lee HJ, Cheon YJ. (2020) Guidelines for the management of extravasation. J Educ Eval Health Prof. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.21

- Kreidieh FY, Moukadem HA, El Saghir NS. (2016) Overview, prevention, and management of chemotherapy extravasation. World J Clin Oncol. doi:10.5306/wjco.v7.i1.87.

- Salem H & Sidell FR. (2005) Blister Agents/Vesicants. In: Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Second Edition). Philip Wexler: Ed. Academic Press (pp.319-323)

Further Reading