There is no clear consensus on when exactly cells decide to divide. For four decades, the answer provided in the textbook was that this decision takes place in the initial phase of the existence of a cell—that is, soon after a mother cell divides into daughter cells.

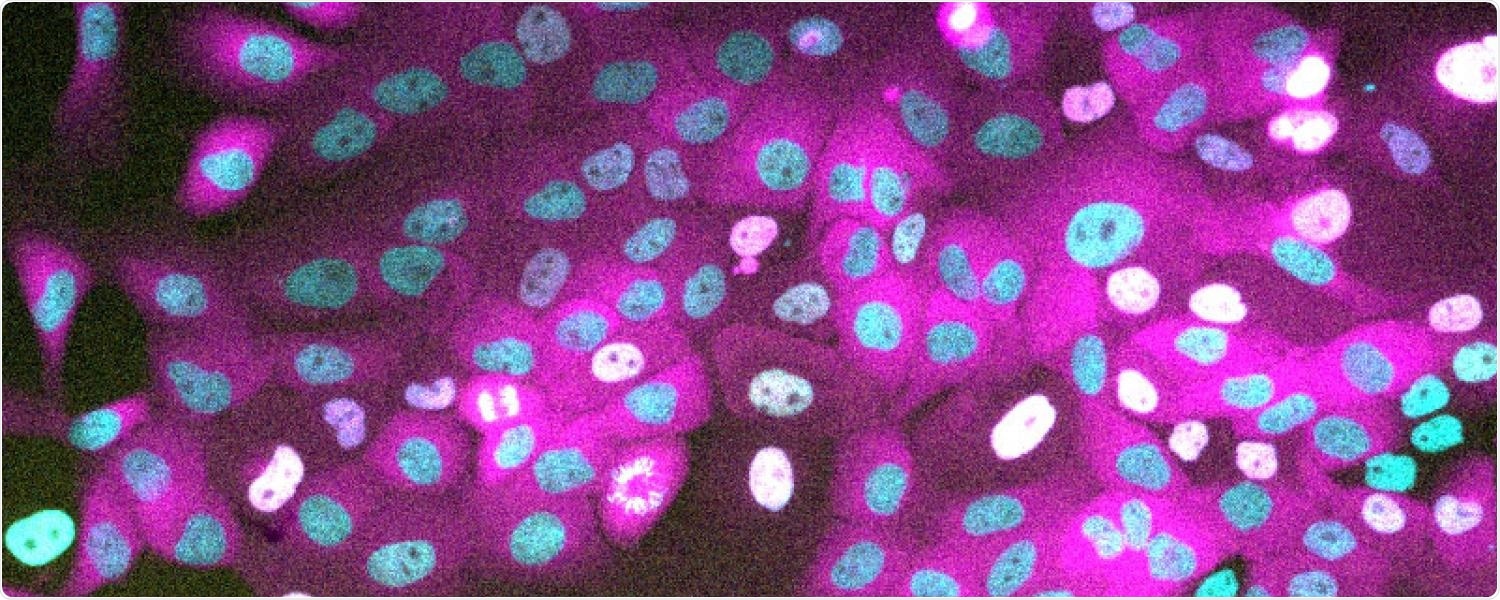

Cells expressing a nuclear marker (H2B) in cyan, a cell-cycle protein (Cyclin D1) in yellow and a proliferation marker (CDK2 activity sensor) in magenta. Image Credit: Mingwei Min.

However, scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) have discovered that it is, in fact, the mother cell that decides about the division of its daughter cells.

Detailed in a new research recently published in the Science journal, this finding provides a deeper understanding of the cell cycle by making use of advanced imaging technologies, and may hold implications for cancer drug therapy treatments.

“We see something different than what’s in the textbooks,” stated Sabrina Spencer, assistant professor of biochemistry and the study’s senior author.

Cells decide to divide based on the number of growth factors, or mitogens, they sense in their environment. Mitogen availability fuels the signal to proliferate—that is, duplicate the contents of the cells and split into two daughter cells. All these are part of the cell cycle mechanism.

Tumor cells can penetrate the cell cycle even in the absence of growth factors, added Spencer. That is part of why these cells proliferate extensively—the cell cycle turns out to be dysregulated and growth persists on their own volition.

Greater insight into when and why cells select to proliferate may help researchers to customize or expand the timing of cancer drug treatments.

During their experiments, the scientists discovered that the daughter cells do not decide on their own whether to divide or not, but instead, they decide whether they are committed to another cell cycle or not, soon after the mother cell division. This means that the decision was reached in the earlier cell cycle, because these daughter cells were already born either on one path or another, explained Spencer.

That got us thinking that maybe all the sensing of the environment is actually happening in the mother cell cycle.”

Sabrina Spencer, Study Senior Author and Assistant Professor of Biochemistry, University of Colorado Boulder

Earlier textbook experiments had to initially remove all growth factors to synchronize the cycling of cells, which disrupts the behavior of the cell cycle. However, this latest study employed time-lapse microscopy as well as cell tracking technologies, which enabled the researchers to image cells performing their own processes and on their own time.

“Doing the experiment this way led to very different results,” added Spencer.

The scientists monitored scores of cells over a period of 48 hours, through computational cell tracking that can monitor the same kind of cell via hundreds of sequential images. Even a decade ago, not many laboratories were able to track cells even for a few hours, Spencer elaborated.

Signals and memory

The researchers’ next question was: when does a cell in the mother cell cycle decide on the need for daughter cells’ division? To answer this question, the scientists subsequently removed and substituted the growth factors, which send the signal for the cell to divide, for many hours at varying stages in the mother cell cycle.

The researchers discovered that the daughter cells were less likely to divide if these growth factors are removed from the mother cell for a longer period. In case the growth factors were removed for over nine hours, none of the daughter cells underwent cell division.

We found that no matter when you blocked this signaling, cells can sense it. And not only can they sense it, they can remember that information for many hours, all the way through to the daughter cell cycle.”

Mingwei Min, Study First Author and Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Biochemistry and BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder

If cells are repeatedly sensing the growth factor signaling—as was discovered by this latest study, rather than only in the first stage of the daughter cycle—cancer drugs are expected to have a longer window than earlier to offer therapeutic effects.

However, how the cells are able to recall the availability of growth factors? This key lies in a protein called Cyclin D.

Cyclin D levels usually increase during the second half of the cell cycle in the mother cell; however, when growth factors were eliminated and substituted in the experiment, Cyclin D levels were less towards the end of the mother cell cycle, discovered the study.

With the availability of fewer Cyclin D levels, the daughter cells have less of their required thing to be able to divide.

The fact that cells can store memory—or integrate past history—of growth factor availability is a new finding. The combination of fluorescent sensor design, long-term time-lapse microscopy, and cell tracking is really our forte that enabled this discovery.”

Sabrina Spencer, Study Senior Author and Assistant Professor of Biochemistry, University of Colorado Boulder