Chronic pancreatitis, or persistent inflammation of the pancreas, is a known risk factor that leads to the development of pancreatic cancer, which is the third-deadliest cancer in the United States.

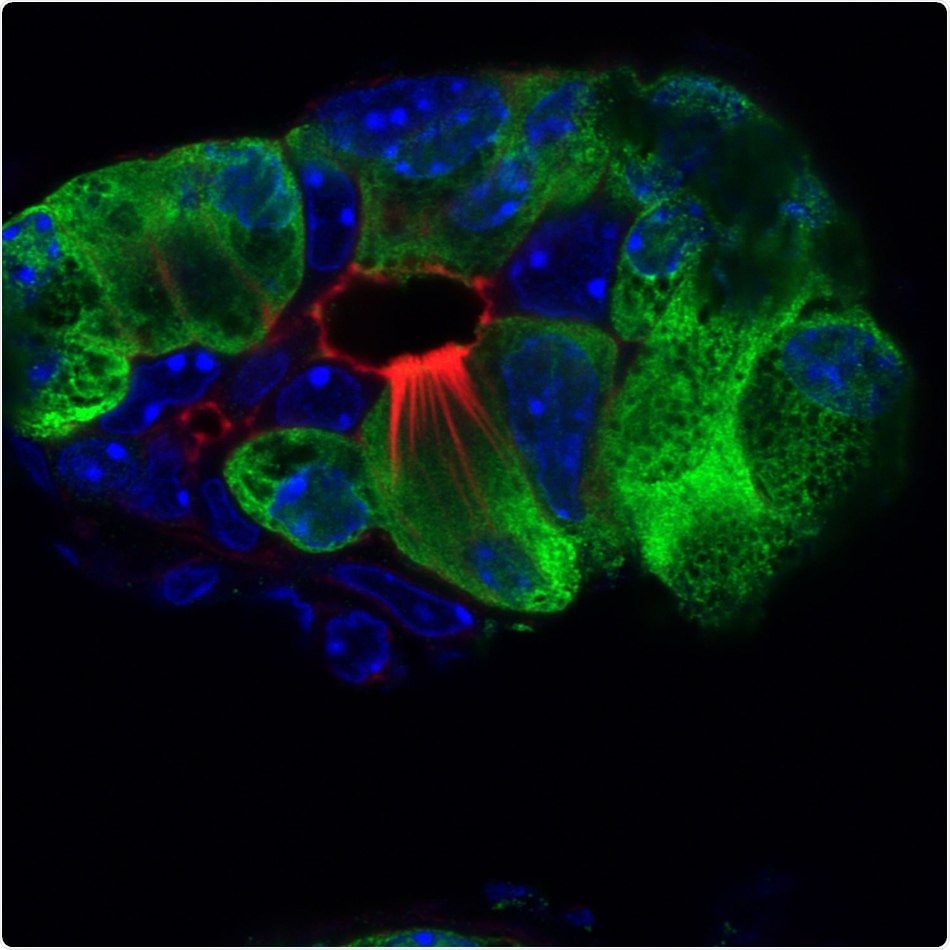

Pancreatitis tuft cells (red, microvilli and actin rootlets) in the injured pancreas (green); nuclei (blue). Image Credit: Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Tuft cells, that is, cells that are susceptible to chemical (chemosensory) alterations usually found in the respiratory tract and intestines, had earlier been identified in the pancreas, but their function has continued to remain a major mystery.

Recently, a team of researchers from Salk Institute headed by Professor Geoffrey Wahl and Staff Scientist Kathleen DelGiorno had revealed how tuft cells are formed during pancreatitis and the unexpected role of these cells in immunity, utilizing mouse models of pancreatitis.

These outcomes were published in the Frontiers in Physiology journal on February 14th, 2020, which led to the development of novel biomarkers to test for pancreatic cancer and pancreatitis.

By understanding these early stages of pancreas disease, we hope our work will lead to the development of new strategies to diagnose and treat pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer early on.”

Geoffrey Wahl, Study Co-Corresponding Author and Professor, Gene Expression Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Wahl also holds the Daniel and Martina Lewis Chair in the Gene Expression Laboratory at Salk Institute.

The pancreas can be described as an abdominal organ that has a vital role to play in digestion and in the regulation of blood sugar levels. But despite these facts, researchers had only a little understanding of how the pancreas is able to recover from injuries, like pancreatitis, or combats pancreatic cancer.

A large part of the pancreas is made up of acinar cells that create and release digestive enzymes. Acinar cells are also capable of converting into another type of cell known as a tuft cell.

Researchers have a minimal idea about the functions of tuft cells, but previous work had revealed that intestinal tuft cells support the immune response during parasitic infections by secreting the protein IL-25.

Since cancer has been called ‘the wound that never heals, we wanted to investigate how the pancreas heals from pancreatitis to better understand pathways that may be co-opted by cancer.”

Razia Naeem, Study Co-First Author and Laboratory Technician, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The scientists employed a combination of methods such as imaging, histology, and molecular approaches to define the populations of tuft cells in pancreatitis mouse models.

Although the pancreas does not usually contain tuft cells, the scientists observed that during pancreatitis, acinar cells go through intricate modifications to transform into tuft cells, all as a normal part of pancreatic injury and recovery.

This change was found to be analogous to a reserve soldier (acinar cell) who should change from civilian clothes into that of a soldier (tuft cell) to combat the enemy of inflammation.

The scientists also noticed the secretion of IL-25 by the pancreatitis-induced tuft cells to encourage immune response just like the one that had earlier been observed in the intestine. The tuft cells, thus, may play a significant role in modulating the immune system during the development of pancreatitis.

The researchers analyzed the formation of tuft cells in seven strains of mice to observe if any changes occurred during the development of pancreatitis. Interestingly, the scientists discovered that the formation of tuft cells did not take place in all strains of mice.

Animals that were the most genetically diverse produced the most number of tuft cells, implying that the formation of tuft cells was either regulated genetically or by impacts on gene expression or epigenetics.

The genetic susceptibility of tuft cell formation may represent a critical factor in pancreatitis formation, severity and progression to cancer in humans. Our work demonstrates that it’s important to use the right mouse model to study pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer for there to be relevance to humans.”

Kathleen DelGiorno, Study First and Co-Corresponding Author, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

According to Wahl, the researchers’ work reveals that using genetically diverse mice can represent the complex human genome in a more optimized way, enabling more translatable modeling of disease in the laboratory. The results may imply that certain people may be more susceptible to develop pancreatitis than others.

The researchers are now planning to follow up on their gene expression studies to pinpoint the types of genes that govern the formation of tuft cells in pancreatitis and whether these cells have an impact on the progression of pancreatic cancer.

The researchers’ biggest expectation is that their study results will present new opportunities for developing more targeted therapies for pancreatitis and cancer.

Source:

Journal reference:

DelGiorno, K. E., et al. (2020) Tuft Cell Formation Reflects Epithelial Plasticity in Pancreatic Injury: Implications for Modeling Human Pancreatitis. Frontiers in Physiology. doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00088.