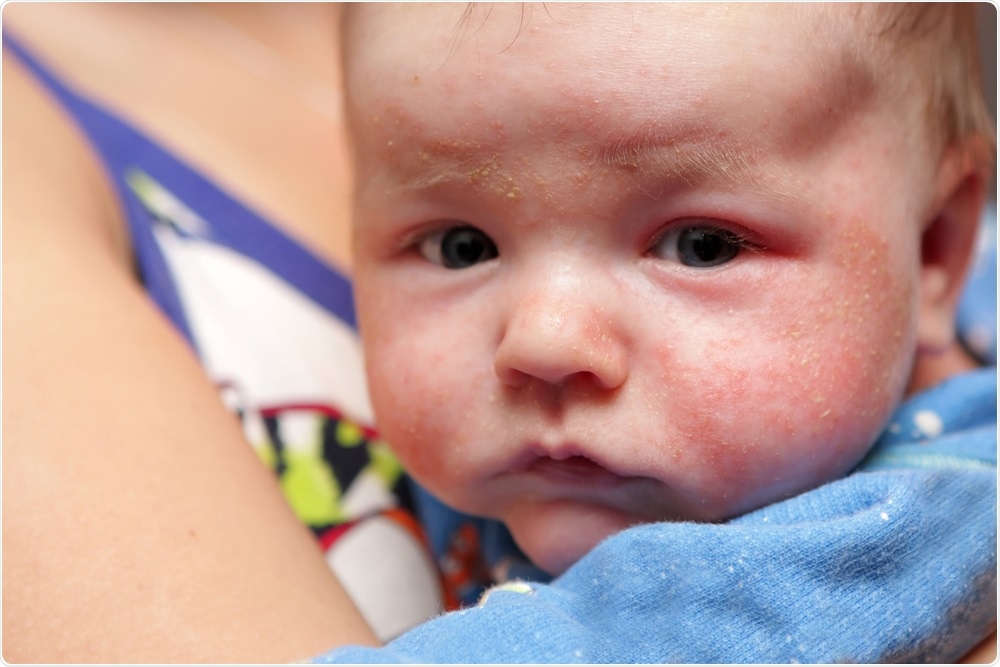

A link has been discovered between a common gene defect and eczema, nasal blockage, and wheeze among babies as young as six months, according to a new study at Brighton and Sussex Medical School (BSMS).

Image Credit: Chubykin Arkady/Shutterstock.com

The research raises new questions about how soon in life these defects could start affecting babies, resulting in serious health problems, and suggests treatment targeted towards children carrying these genetic defects started soon after birth could improve their lives.

The protein filaggrin is present in the skin and nasal cavity, helping to maintain the skin barrier, and previous studies have shown defects in the gene synthesizing filaggrin are strongly linked to the risk of developing eczema and how serious eczema and asthma turned out to be over childhood.

In the first study of this kind, we recruited mothers in the antenatal clinic and followed up the babies through infancy, in order to define the link between these gene defects, the resultant skin problem, and eczema, wheeze and nasal blockage, in early infancy. Our striking finding establishing this link could mean that some babies with these gene defects could be getting primed from birth or soon after, for a life of suffering from an allergy-related disease."

Professor Somnath Mukhopadhyay, Chair in Paediatrics at BSMS

The GO-CHILD study recruited 2,312 pregnant women in England and Scotland, who gave a cord blood sample at birth or saliva in infancy for genotyping of the babies.

Babies were followed up for symptoms related to allergic diseases such as dry skin, eczema, wheeze, and nasal blockage, at the ages of 6, 12, and 24 months by postal questionnaires sent to the carers.

The gene defects made eczema, wheeze, and nasal blockage worse at six months. While the defects were affecting eczema at one year, they were no longer worsening wheeze and nasal blockage at this age.

At two years, they were principally worsening eczema and nasal blockage, but not affecting wheeze. "The problems affecting the child change over time, filaggrin gene variation representing one major ensemble within the grand orchestra of allergic disease," said Professor Mukhopadhyay.

He added: "The use of simple emollients from birth targeted towards those who have these gene defects may help correct this problem, thus alleviating suffering in infancy and also through life. This new approach for targeting treatment according to genetic information is known as precision or personalized medicine and a future trial could represent the first application of this exciting and novel approach in little babies otherwise primed to develop chronic disease from an early age.

This skin barrier defect leads to the selective entry of allergens to increase the burden of disease. Whether such barrier defects could make us more vulnerable to agents causing infection, such as viruses, has not yet been addressed. We are in the midst of a pandemic where some people are affected but many are not. Could a defective outer barrier in skin and mouth be making some of us more vulnerable? If so, would identifying patients carrying these defects help us better protect those that are more vulnerable?"

The study was funded by Sparks Children's Medical Research Charity and the Rockinghorse Children's Charity. It was published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the world's top allergy journal, and can be accessed at https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(20)30348-1/abstract