Certain antibodies are known to protect humans from viral infections—or perhaps not?

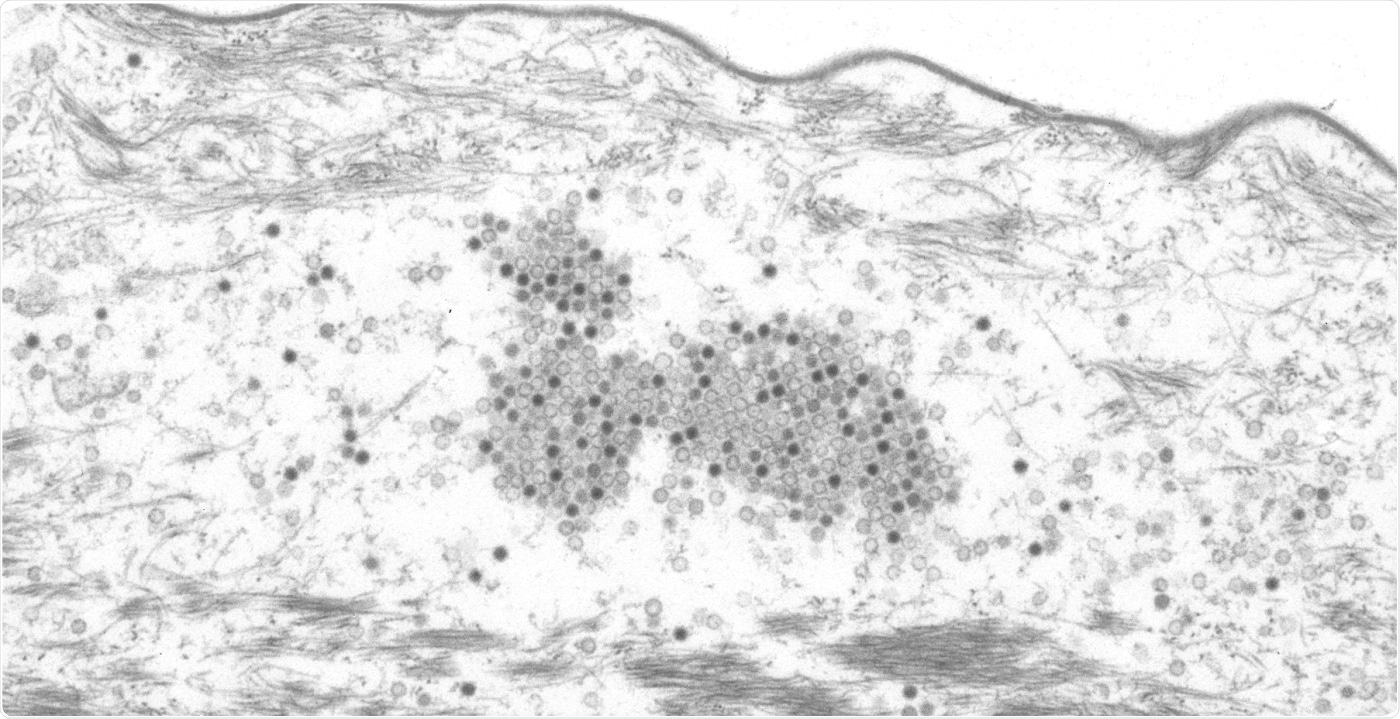

Papillomaviruses in the stratum corneum of a skin tumor of a Mastomys coucha. Image Credit: © Michelle Neßling/DKFZ.

At the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), scientists have analyzed the immune response to papillomaviruses in mice and found a novel mechanism that was not known before.

The microbes use this mechanism to deceive the immune system: at the initial stage of the infection cycle, the microbes create a longer protein version that encircles the viral genome. The body then generates antibodies against this specific protein, but they are ineffective at combating these microorganisms.

A broad variety of defense strategies are found in the human immune system. These defense strategies guard the body against the pathogens; one of these strategies involves creating antibodies against bacteria and viruses. But over time, these microorganisms develop extensive ways to evade the immune system.

Researchers already know about some of these defense strategies. But in the case of human papillomaviruses (HPV), they have only known about such defense strategies in innate and already prevalent immunity and not in adaptive immunity, up until now. The adaptive immunity does not develop until microbes penetrate the body and is related to the generation of antibodies.

Frank Rösl and his co-workers from German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) under the guidance of Daniel Hasche have now detected a novel mechanism by which skin-specific cutaneous papillomaviruses deceive the immune system.

Specific cutaneous HPV, like HPV8 and HPV5, are known to occur as natural infections on the skin. But they are not sexually transmitted and instead passed on from mothers to the newborns. Therefore, family members are often colonized with the same types of HPV. An infection usually goes undetected, since the body has the ability to overcome it.

But based on the individual status of persons’ immune system, such as their age, genetic predisposition, and other external factors like UV radiation, specific cutaneous types of HPV can activate the division of cells in their host cells. This causes changes in the skin and, in rare cases, leads to the development of a squamous cell carcinoma, also called fair-skin cancer.

The experiments were performed in a specific mouse species, called Mastomys coucha, which, similar to humans, can be infected with cutaneous papillomaviruses soon after birth and generate certain antibodies against the pathogen. Combined with UV radiation, infected animals could develop squamous cell cancer.

The immune system of animals creates antibodies against a pair of viral proteins L1 and L2 that constitute the virus particles, also known as capsids. Such antibodies can inhibit the viruses from penetrating the host cells and thus neutralize the pathogen.

But the experiments performed by the DKFZ team demonstrated that apart from the normal L1 protein, the pathogens also create a longer version. Actually, the latter is incapable of taking part in the formation of the viral capsid. Rather, it serves as a sort of bait against which the immune system directs its reaction and eventually creates particular antibodies.

But the researchers successfully showed that such antibodies are ineffective against the papillomavirus. Rather than neutralizing the infectious pathogen via binding to the L1 protein, the antibodies simply bind the nonfunctional protein employed as bait.

When the immune system is actively creating such non-neutralizing antibodies, the pathogen can progress to replicate and proliferate all through the body. The virus takes several more months before neutralizing antibodies are created that target the regular L1 protein and eventually the infectious pathogens themselves.

In both rodents and humans, in almost all HPV types that can cause cancer, the L1 gene is designed such that a longer version of the protein can be produced. This is also true for high-risk HPV types such as HPV16 and HPV18, which can cause cervical cancer. It therefore appears to be a common mechanism that enables the viruses to replicate and spread efficiently during the early stage of infection.”

Daniel Hasche, Division of Viral Transformation Mechanisms, German Cancer Research Center

“The fact that antibodies against papillomaviruses can be detected is therefore not necessarily associated with protection against infection. This will need to be taken into account in future when evaluating and interpreting epidemiological studies,” Frank Rösl concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Fu, Y., et al. (2020) Expression of different L1 isoforms of Mastomys natalensis papillomavirus as mechanism to circumvent adaptive immunity. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57626.