A new study has revealed how a disease-causing parasite is able to resist the present range of therapies. The study was recently published in the open-access journal, eLife.

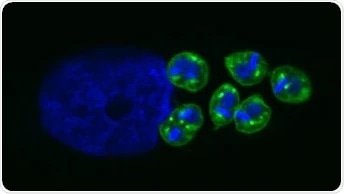

Intracellular amastigotes inside a mammalian host cell. Image Credit: Dumoulin et al.

The study conducted in human cell cultures infected with Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi)—the parasite that leads to Chagas disease)—indicates that the metabolic state of this pathogen impacts the effectiveness of azole drugs that block its growth. These latest findings may help develop more effective antimicrobial therapies.

Chagas disease, also called American trypanosomiasis, can trigger a sudden, brief (acute) illness, or it may be a persistent (chronic) condition.

According to the World Health Organization, approximately six to seven million individuals around the world are estimated to be infected with the T. cruzi pathogen that is responsible for causing the Chagas disease. While symptoms can range from mild to severe, they do not usually appear until the chronic phase of the disease.

The goal for the treatment of Chagas and other infectious diseases is to eliminate the pathogen from the infected host. There are a few ways in which pathogens can survive antimicrobial treatment. One of the less explored options is the impact of their metabolic and environmental diversity (or heterogeneity) on the effectiveness of a given treatment, and we wanted to find out if these factors play a role in T. cruzi’s drug resistance.”

Peter Dumoulin, Study First Author, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health

Dumoulin is also a Postdoctoral Fellow at senior author Barbara Burleigh’s laboratory, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, United States.

The T. cruzi life-cycle has an intracellular phase, where the pathogens become amastigotes—that is, replicative forms of the parasite that continue to remain in the infected host. The researchers’ study demonstrated that the sensitivity of amastigotes to azole medications increases considerably in the presence of specific levels of glutamine, a form of amino acid that does not depend on the growth rate of the parasite.

Additional metabolic labeling and inhibitor analyses revealed that the glutamine metabolism of T. cruzi results in increased production of sterols or steroid alcohols, together with an accompanying buildup of non-standard sterols and toxicity to the pathogen in the presence of azoles.

These latest findings indicate that metabolic heterogeneity in the interaction between the host and the parasite may contribute to the failure of certain drugs to achieve sterile treatment, demonstrating a new connection between drug efficacy and metabolism.

Our work provides further evidence that the metabolic state of a microorganism is important for determining its susceptibility to antimicrobials, and lays the groundwork for further studies.”

Barbara Burleigh, Study Senior Author and Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard Chan School

“Gaining a better understanding of metabolism in T. cruzi and other parasites, and why current drug candidates can fail to treat infection, could lead to more effective therapies for Chagas disease and other infections,” Professor Burleigh concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Dumoulin, P. C., et al. (2020) Glutamine metabolism modulates azole susceptibility in Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.60226.