Taking a cue from light-sensing bacteria that live close to hot oceanic vents, synthetic chemists from Rice University have identified a mild process to produce useful hydrocarbons, called alkenes, or olefins.

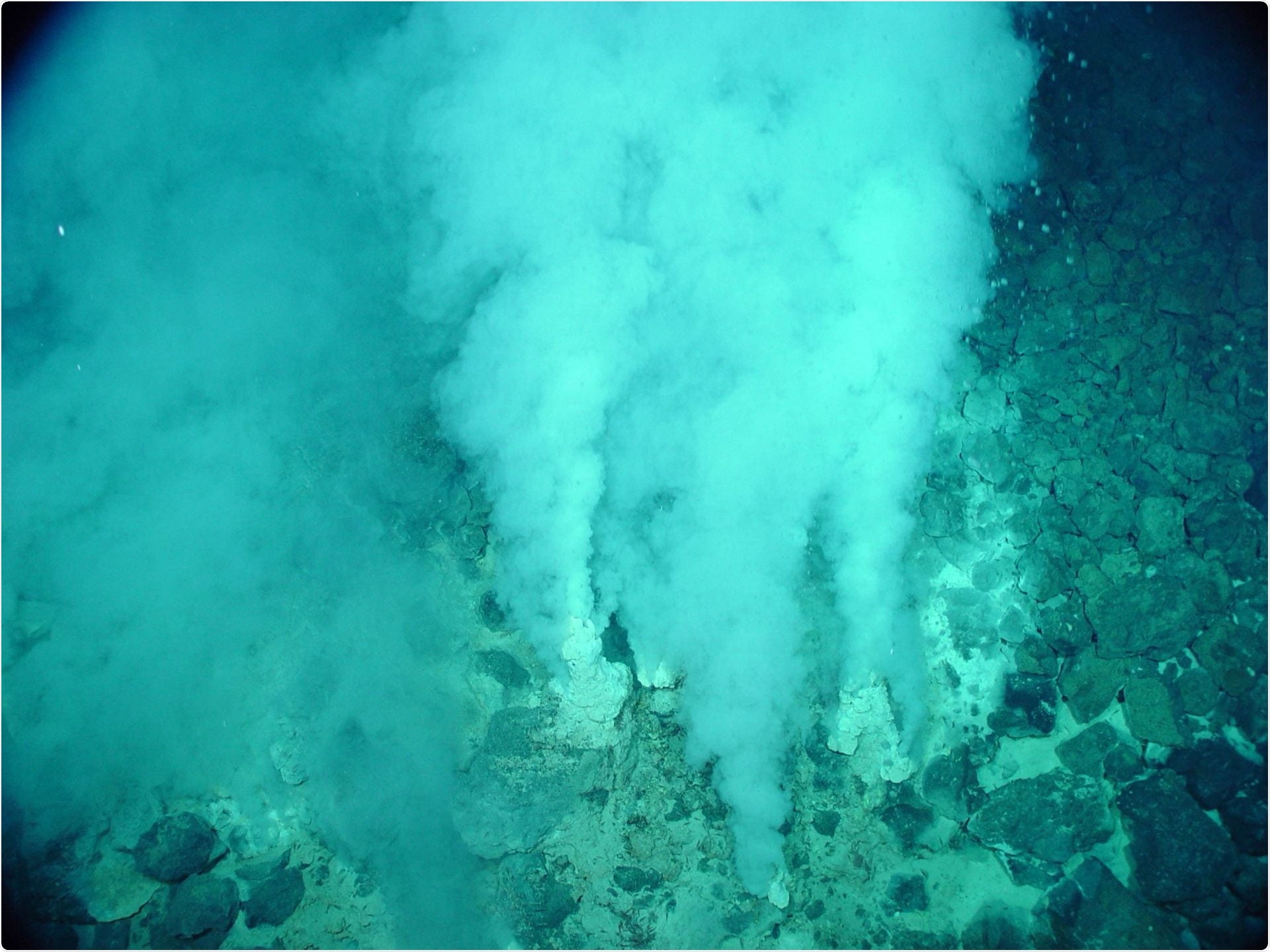

Inspired by light-sensing bacteria that thrive near hydrothermal vents like this one, synthetic chemists use vitamin B12 to catalyze valuable hydrocarbons known as olefins, or alkenes. Image Credit: Rice University.

Just like how bacteria use vitamin B12, the team used the same vitamin and effectively removed aggressive chemicals. Such chemicals often make it crucial to use precursor molecules for the production of agrochemicals and drugs.

The new open-access work was published in Chemical Science, a journal from the Royal Society of Chemistry. It was performed by Julian West, an assistant professor of chemistry, and his collaborators.

“Arguably, these olefins, or alkenes, are the most useful functional groups in a molecule. A functional group is like a foothold in climbing: It lets you get to where you want to go, what you want to make,” stated West, who was recently named one of 30 Under 30 rising stars in science in Forbes Magazine.

We’ve had methods to make olefins for a long time, but a lot of these classic methods—late 19th or early 20th century—use incredibly strong bases, things that would burn you and would definitely burn your molecule if it had anything sensitive on it. The other issue is that such harsh conditions might be able to make this olefin, but you might make it in the wrong place.”

Julian West, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Rice University

For many years, chemists have been striving to develop a mild process that would allows them to choose the functional form of the olefin.

The process developed by Rice University took its cue from laboratories that identified metal catalysts to enhance the process and from others that explored light-sensitive bacteria, called thermus thermophilus, that live close to underwater thermal vents.

They have a lot of unusual enzymes. One of them is called carH, a photoreceptor like a bacterial retina that developed on a parallel evolutionary path to what led to our eyes.”

Julian West, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Rice University

The CarH enzyme integrates cobalt and vitamin B12. This cobalt reacts with light and supports the development of an alkene, which consequently alerts the bacteria to the presence of light.

“Instead of needing heat and strong bases, it only needs light energy,” West added. According to him, the alkene “is just a byproduct of the bacteria. It doesn’t really care. But we thought we could take this cue from nature.”

The team from Rice University used vitamin B12, and the cobalt it contains with baking soda or sodium bicarbonate, as a mild base to produce the olefins at room temperature and under blue light.

An unexpected aspect of the study was the emergence of remote elimination, through which the team was able to place hydrogen atoms to ease additional reactions. That may result in two-step procedures for particular products.

Basically, we found we could make olefins and not just isolate them. In the same flask at the same time, we can have a second reaction and turn them into something else. This could be a plug-and-play method where we can start to sub in different molecules.”

Julian West, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Rice University

West added that the researchers are working on differences that can be upgraded for the industrial production of various plastics, including polypropylene, based on olefins.

“B12 is a little too complicated for commodity-scale synthesis. But it’s great for fine chemicals, and we can buy it from any number of suppliers,” West concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Bam, R., et al. (2020) Mild olefin formation via bio-inspired vitamin B12 photocatalysis. Chemical Science. doi.org/10.1039/D0SC05925K.