A research team, headed by USC Stem Cell researcher Michael Bonaguidi, Ph.D., has revealed that neural stem cells (NSCs)—that is, the stem cells of the nervous system—age quickly. The study was recently published in the Cell Stem Cell journal.

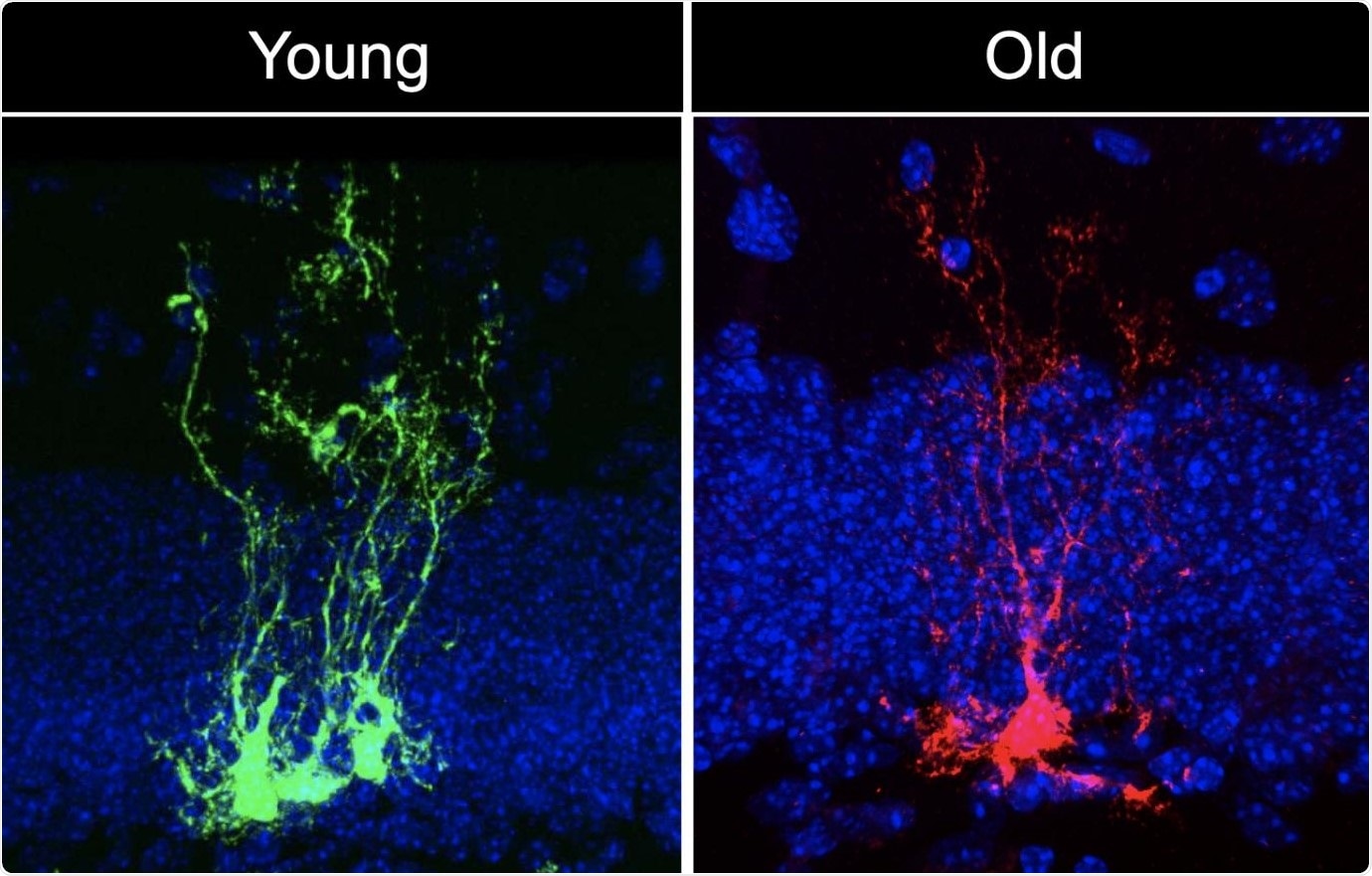

Neural stem cell clones in young (green) and old (red) mouse brains. Image Credit: Albina Ibrayeva/Bonaguidi Lab.

There is chronological aging, and there is biological aging, and they are not the same thing. We’re interested in the biological aging of neural stem cells, which are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time. This has implications for the normal cognitive decline that most of us experience as we grow older, as well as for dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and brain injury.”

Michael Bonaguidi, Assistant Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Gerontology and Biomedical Engineering, Keck School of Medicine of USC

The research work involved Albina Ibrayeva, the study's first author and a Ph.D. candidate in the Bonaguidi Lab at USC’s Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research, and her collaborators who analyzed the brains of old, young, and middle-aged mice.

By monitoring individual NSCs over a period of many months, the team detected “short-term NSCs” that rapidly differentiate into more specialized neurons and also identified “long-term NSCs” that continuously split and replicate themselves to sustain a continuous reserve of stem cells and have the capacity to produce several different types of cells in the brain.

But as the mice aged, the major population of long-term NSCs divided less frequently and failed to sustain their numbers.

The researchers then looked at thousands of genes in the long-term NSCs, which were dividing less frequently and had entered an inactive state called quiescence. They found that the gene activity of the quiescent NSCs differed significantly between young and middle-aged animals.

As predicted, there were genetic changes that regulate the division of long-term NSCs and also produce new neurons and other types of brain cells. Surprisingly, there were several significant changes in the gene activity associated with biological aging at much younger ages than expected.

Such pro-aging genes make it increasingly challenging for cells to control their genetic activity, repair DNA damage, regulate inflammation, and manage other stresses. Among the pro-aging genes, the team was highly fascinated by Abl1, which served as the core of a network of interconnected genes.

We were interested in the gene Abl1, because no one has ever studied its role in neural stem cell biology—whether in development or in aging.”

Albina Ibrayeva, Study First Author and PhD Candidate, Keck School of Medicine of USC

The researchers were able to suppress the activity of the Abl1 gene by using a current, FDA-approved chemotherapy drug, known as Imatinib. For six days, the team administered doses of Imatinib into the older mice. Once the activity of the Abl1 gene was blocked by the drug, NSCs started to separate and proliferate in the hippocampus—the region of the brain responsible for memory and learning.

We’ve succeeded in getting neural stem cells to divide more without depleting, and that’s step one. Step two will be to induce these stem cells to make more neurons. Step three will be to demonstrate that these additional neurons actually improve learning and memory. Much work remains to be done, but this study marks exciting progress towards our goal of identifying prescription drugs that could rejuvenate our brains as we grow older.”

Michael Bonaguidi, Assistant Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Gerontology and Biomedical Engineering, Keck School of Medicine of USC

Source:

Journal reference:

Ibrayeva, A., et al. (2021) Early stem cell aging in the mature brain. Cell Stem Cell. doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2021.03.018.