For the first time, a research team from Monash University has discovered that mutations in a specific gene cause mitochondrial disease.

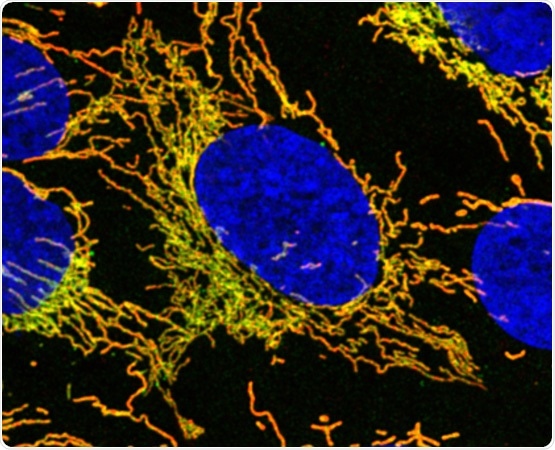

Mitochondria (yellow-green) around the cell nucleus (blue). Image Credit: Dr Matthew Eramo.

The discovery, led by Professor Mike Ryan of Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute and published in the journal PNAS, demonstrates that TMEM126A, a gene accountable for the loss of hearing and vision, produces a protein that aids in the formation of an essential energy generator in mitochondria.

Therefore, if this gene is faulty, it decreases mitochondrial activity and impairs energy production, shedding light on why mutations cause disease.

Mitochondria are vital structures found inside living cells that perform an important part in energy conversion. Their task is to process oxygen and absorb proteins and sugars from the food humans consume to provide the energy needed by the body to work properly. Mitochondria provide 90% of the energy required by the body to survive.

Mitochondrial disease is a hereditary, chronic illness that can manifest at birth or develop later in life as mitochondria struggle to provide enough energy for the body to function properly.

Because of the high energy needs to transmit information to the brain, the cells of the optic nerve and inner ear are especially sensitive to mitochondrial defects, although mitochondrial disorders can affect virtually any part of the body.

The researchers discovered that TMEM126A loss leads to an isolated complex I deficiency—a prevalent type of mitochondrial disease in which an essential enzyme named complex I is diminished—and that the TMEM126A protein attaches to a variety of complex I subunits and additional proteins that help create the enzyme, called assembly factors.

Now we know that TMEM126A is important in helping to build this protein needed to provide energy for the mitochondria organelles, we can look at future therapies that can perhaps bypass TMEM126A function and find other ways to help cells make energy.”

Mike Ryan, Professor, Biomedicine Discovery Institute, Monash University

Dr. Luke Formosa, who is the first author of the study, concluded: “Now that we know what TMEM126A does in mitochondria, we can start to investigate treatments that might work for individuals with mutations in this gene, which could lead to a less severe loss of vision and hearing.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Formosa, L. E., et al. (2021) Optic atrophy–associated TMEM126A is an assembly factor for the ND4-module of mitochondrial complex I. PNAS. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019665118.