When it comes to differentiating between a healthy cell and an infectious cell that has to be killed, the immune system’s killer T cells might make mistakes.

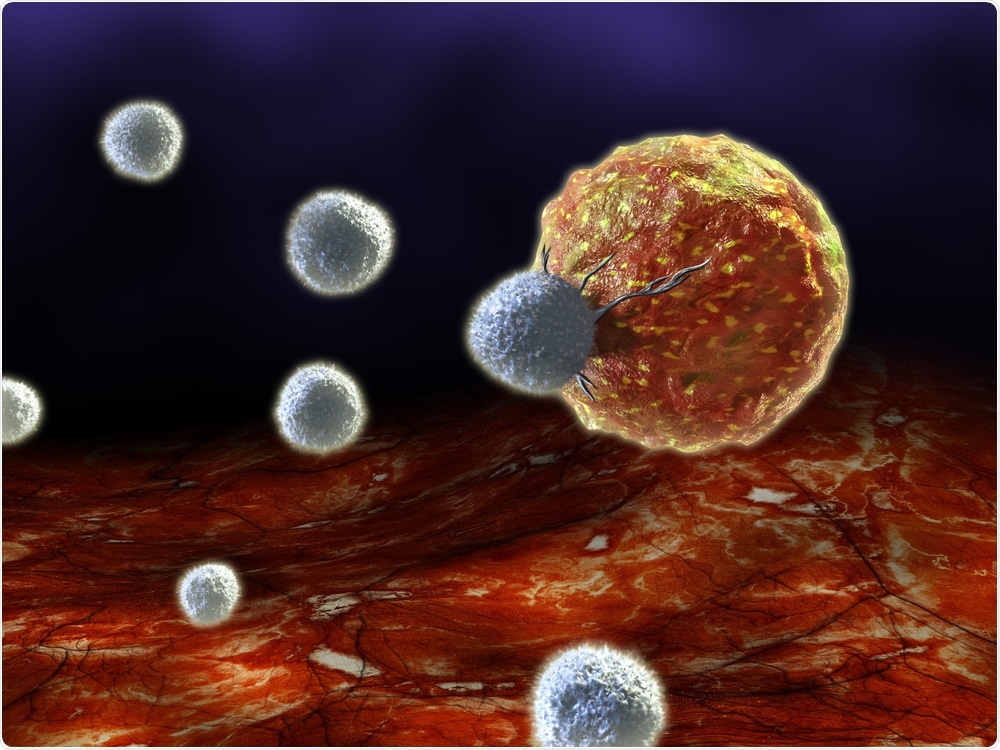

T cells attacking a cancer cell. Image Credit: Andrea Danti/Shutterstock.com

This finding was published in eLife and challenges scientists’ long-held view that T cells were practically perfect in distinguishing between friend and foe. The findings might lead to novel approaches to treating autoimmune illnesses, which cause the immune system to attack the body, or to advancements in cutting-edge cancer treatments.

It is commonly assumed that T cells can distinguish between infected and healthy cells depending on how strongly they can adhere to molecules known as antigens on the surface of each. They bind closely to antigens originating from bacteria or viruses but less firmly to antigens found on normal cells.

Recent autoimmune disease research suggests that T cells can fight otherwise normal cells if they express an exceptionally large number of human antigens, even if they bind very weakly.

We set out to resolve this discrepancy between the idea that T cells are near perfect at discriminating between healthy and infected cells based on the antigen binding strength, and clinical results that suggests otherwise. We did this by very precisely measuring the binding strength of different antigens.”

Johannes Pettmann, Study Co-First Author and D.Phil Student, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology and Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, UK

The researchers determined how firmly T cell receptors connect to a variety of antigens and then observed how T cells from healthy persons react to cells with varying concentrations of these antigens.

Our methods, combined with computer modelling, showed that the T cell’s receptors were better at discrimination compared to other types of receptors. But they weren’t perfect—their receptors compelled T cells to respond even to antigens that showed only weak binding.”

Anna Huhn, Study Co-First Author and D.Phil Student, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford

“This finding completely changes how we view T cells. Instead of thinking of them as near-perfect discriminators of the antigen-binding strength, we now know that they can respond to normal cells that simply have more of our own weakly binding antigens,” added Enas Abu-Shah, Postdoctoral Fellow, Kennedy Institute and the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, and also a co-first author of the study.

Technical concerns in assessing the degree of T cell receptor binding in prior research, according to the authors, likely contributed to the incorrect conclusion that T cells are perfect discriminators, emphasizing the need for adopting more accurate measures.

Our work suggests that T cells might begin to attack healthy cells if those cells produce abnormally high numbers of antigens. This contributes to a major paradigm shift in how we think about autoimmunity, because instead of focusing on defects in how T cells discriminate between antigens, it suggests that abnormally high levels of our own antigens may be responsible for the mistaken autoimmune T-cell response.”

Omer Dushek, Study Senior Author and Associate Professor, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford

“On the other hand, this ability could be helpful to kill cancer cells that mutate to express abnormally high levels of our antigens,” added Dushek, Senior Research Fellow in Basic Biomedical Sciences at the Wellcome Trust, UK.

According to Dushek, the finding also opens up new areas of study to increase T cell discriminating abilities, which might be useful in decreasing the autoimmune side-effects of many T-cell-based treatments without compromising these cells’ capacity to destroy cancer cells.

Source:

Journal reference:

Pettmann, J, et al. (2021) The discriminatory power of the T cell receptor. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.67092.