UC San Francisco researchers have demonstrated that gene-edited cellular treatments can effectively treat cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders, prospectively paving the path for the development of less expensive cellular medicines to address diseases for which there are very few viable options now.

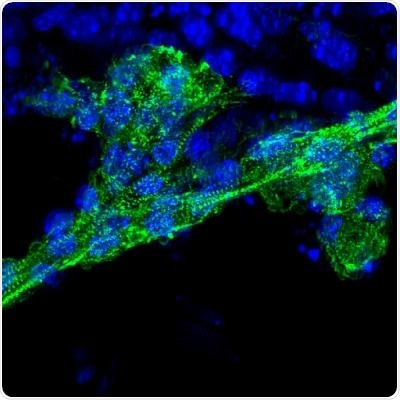

Immune fluorescence of HIP cardiomyocytes in a dish. Image Credit: University of California - San Francisco.

The study, which was conducted in mice, is the first to show that products derived from specifically engineered induced pluripotent stem cells known as “HIP” cells may successfully treat severe diseases while evading the immune system.

The study results undermine the immune response, which is a primary cause of transplant failure and a hurdle to the use of engineered cells as therapy.

We showed that immune-engineered HIP cells reliably evade immune rejection in mice with different tissue types, a situation similar to the transplantation between unrelated human individuals. This immune evasion was maintained in diseased tissue and tissue with poor blood supply without the use of any immunosuppressive drugs.”

Tobias Deuse, MD, Study First Author and Julien I.E. Hoffman, M.D. Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery, University of California - San Francisco

Deuse’s work is an example of “living therapies,” a new branch of medicine in which treatments are described as living human and microbial cells that have been selected, manipulated, or created to treat or cure disease.

The research was published in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America).

“Universal stem cells” avoid immune detection

According to the researchers, the chances of creating specialized cells in a laboratory that may be transplanted into patients to cure various ailments are promising. The immune system, on the other hand, would readily detect cells obtained from another person and reject them.

As a result, some experts feel that personalized cell treatments must be created from the ground up, starting with a blood sample from each particular patient.

The UCSF team took a different method, employing gene editing to create “universal stem cells” (dubbed HIP cells) that are immune-suppressed and can be used to create “universal cell therapies.”

The researchers looked at how well these cells could treat three major diseases that affect different organ systems: peripheral artery disease, a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and heart failure, which is becoming more of a global epidemic, with over 5.7 million patients in the United States alone and 870,000 new cases every year.

The researchers showed that transplanting specialized, immune-engineered HIP cells into mice with each of these conditions could alleviate peripheral artery disease in the hindlimbs, prevent lung disease in mice with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and alleviate heart failure in mice after myocardial infarction.

The researchers evaluated the treatment’s efficacy using established parameters for human clinical trials concentrating on outcome and organ function to improve the translational component of this proof-of-concept study.

The promise of an affordable option

Deuse, who is also the surgical director of the Transcatheter Valve Program and the director of Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery, wants to see if these universal stem cells may be used to treat other endocrine and cardiovascular diseases.

Because of the unique nature of the method, he believes that a careful and measured introduction into clinical trials is essential. He believes that if more information on human safety is available, it will be easier to predict when HIP cell treatments will be approved and offered to patients.

According to Deuse, one of the major advantages of this technique is that immunity engineering is a cost-effective solution. It would lower the cost of producing universal, high-quality cell therapies, allowing for the treatment of bigger patient groups in the future and facilitating access for patients from underserved communities.

In order for a therapeutic to have a broad impact, it needs to be affordable. That's why we focus so much on immune-engineering and the development of universal cells. Once the costs come down, the access for all patients in need increases.”

Tobias Deuse, MD, Study First Author and Julien I.E. Hoffman, M.D. Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery, University of California - San Francisco