Recent research at Tel Aviv University identified that eosinophils—a kind of white blood cells—are recruited for the fight against cancer metastases in the lungs. Scientists remark that these white blood cells synthesize destructive proteins of their own, along with summoning the immune system’s cancer-fighting T-cells at the same time.

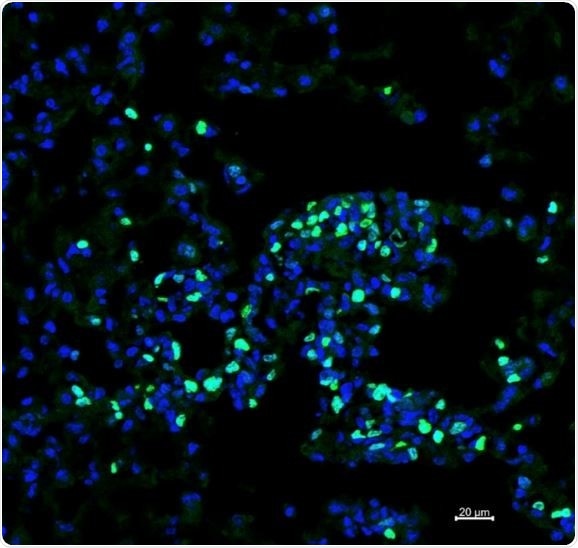

Proliferation metastatic tumor cells in animals with no eosinophils. Image Credit: Tel Aviv University.

The researchers believe that their observations can assist in the development of novel approaches to cancer immunotherapy treatments, based on the collaboration between T-cells and eosinophils.

The research was headed by Professor Ariel Munitz and Ph.D. student Sharon Grisaru of the Department of Microbiology and Clinical Immunology at the Sackler Faculty of Medicine. The study was published in Cancer Research, a prestigious journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The scientists detail that eosinophils are white blood cells of the immune system that generate powerful destructive proteins—primarily intended for combating parasites. But in the modern Western world, where greater levels of hygiene have substantially decreased the threat of parasites, eosinophils often have a negative effect on humans, stimulating phenomena such as asthma and allergies.

Assuming that the destructive power of eosinophils might be useful if turned against cancer cells, the scientists commenced the current research.

We chose to focus on lung metastases for two main reasons: First, metastases, and not the primary tumors, are often the main problem in treating cancer, and the lungs are a major target for the metastasis of many types of cancer. Second, in a preliminary study, we demonstrated that eosinophils gather in tumors developing in mucous tissues like the lungs, and therefore assumed that they would be found in lung metastases as well.”

Ariel Munitz, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Clinical Immunology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine

The scientists analyzed human cancer tissues initially—biopsies from lung metastases taken from breast cancer patients. They identified that the eosinophils reach the lungs and enter the cancer tissues, where they mostly release the destructive proteins they carry.

To analyze the role of eosinophils in metastases, the scientists employed an animal model. They discovered that lung metastases that form in the absence of eosinophils were much bigger than those exposed to eosinophils. These observations led to the conclusion that eosinophils combat cancer efficiently; however, the question persisted: How do they do it?

We observed that when eosinophils are missing, the tissue also lacks T-cells—white blood cells known for fighting cancer. Consequently, we assumed that eosinophils combat cancer through T-cells. Our next task was to understand the mechanism underlying this process.”

Ariel Munitz, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Clinical Immunology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine

A comprehensive analysis of eosinophils recognized in the metastases led to two vital findings: First, eosinophils release huge amounts of chemokines—substances that summon T-cells—in the presence of cancer; and second, the chemokines are released when eosinophils are exposed to two other substances present in the cancer’s environment, named TNF-a and IFN-g.

Alternatively, in response to TNF-a and IFN-g, eosinophils employ the T-cells for reinforcement. Eventually, the arrival and development of T-cells in the affected lungs retards the growth of tumors.

Increasing the number and power of T-cells is one of the main targets of immunotherapy treatments administered to cancer patients today. In our study, we discovered a new interaction that summons large quantities of T-cells to cancer tissues, and our findings may have therapeutic implications.”

Ariel Munitz, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Clinical Immunology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine

Professor Munitz also states, “Ultimately, our study may serve as a basis for the development of improved immunotherapeutic medications that employ eosinophils to fight cancer in two ways: on the one hand, the eosinophils will attack the cancer directly by releasing their own destructive proteins, while on the other, they will increase the number of T-cells in the cancer’s environment.”

“We believe that the combined effect can significantly enhance the effectiveness of the treatment,” remarked Professor Munitz.

Source:

Journal reference:

Grisaru-Tal, S., et al. (2021) Metastasis-entrained eosinophils enhance lymphocyte-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Research. doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0839.