Scientists from the National Institutes of Health recently found a therapy that targets host cells instead of bacterial cells in treating bacterial pneumonia in rodents.

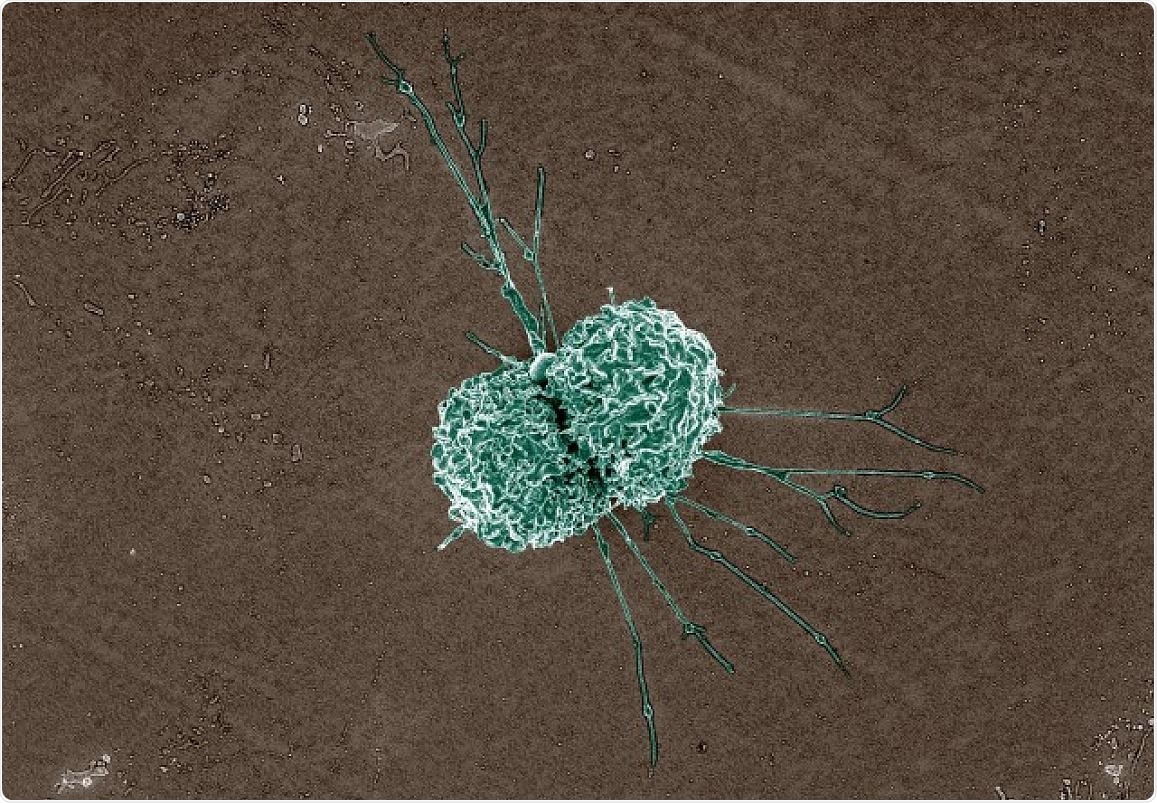

Macrophage Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a macrophage. Image Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The technique involves macrophages—white blood cells of the immune system—that engulf bacteria, and a group of compounds named epoxyeicosatrienoic acids or EETs that are naturally secreted in humans and mice.

The study was published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The World Health Organization states that pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, or pneumococcal pneumonia, is the major cause of pneumonia deaths globally every year. Medical practitioners generally dictate antibiotics to treat this severe lung infection. However, the treatment is not always successful, and in certain cases, the bacteria become resistant.

Matthew Edin, PhD, a scientist at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of NIH, wished to identify a means to magnify the body’s immune system to resolve the infection.

To sustain tissues in a good shape, EETs work to limit inflammation. However, during infections by S. pneumoniae and other microbes, inflammation increases after lung cells trigger specific substances that provoke macrophages to engulf bacteria. Edin and co-workers identified that one way to get macrophages to engulf more bacteria is by decreasing the capability of EETs to limit inflammation.

Edin headed the group that identified that infection triggers a protein named soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) that can degrade EETs. Conversely, when sEH is blocked, EET levels increase, impeding the macrophages’ capability to sense and gobble bacteria. This results in continuous reproduction of the bacteria in the lung, leading to severe lung infection and death.

However, when the EETs are blocked with the help of a synthetic molecule named EEZE, the engulfing capacity of the macrophages increases, resulting in decreased bacterial numbers in the lungs of mice. The researchers observed similar results when they placed bacteria and macrophages harvested from lung and blood samples of human volunteers in test tubes at the NIEHS Clinical Research Unit.

EEZE is safe and effective in mice, but scientists could develop similar compounds to give to humans. These new molecules could be used in an inhaler or pill to promote bacterial killing and make the antibiotics more effective.”

Matthew Edin, Study Co-Lead Author and Scientist, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Darryl Zeldin, MD, Scientific Director of NIEHS and the corresponding author of the research, spent many years analyzing EETs and their effects on the human body. He and his research team identified that EETs offer beneficial cardiovascular effects, like enhancing cell survival after a stroke or heart attack and lowering blood pressure and inflammation.

However, Darryl Zeldin emphasized that the involvement of EETs in the inflammation process can be bad or good based on the context.

EETs can suppress the inflammatory response, which is good, but if they block it too much, they’re going to make it so the macrophages can’t eat the bacteria, which is bad.”

Darryl Zeldin, Study Corresponding Author and Scientific Director, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Edin also stated that certain scientists have examined sEH inhibitors—compounds that impede sEH from degrading EETs—in clinical trials to observe if they can annihilate pain, high blood pressure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He warns that the researchers carrying out these studies should consider the influence of sEH inhibitors on bacterial clearance.

Edin adds, “They should be careful and stop using them if the individual develops pneumonia. Our study demonstrated that blocking sEH means EETs may hamstring macrophages, making a lung infection worse.”

Stavros Garantziotis, MD, medical director of the NIEHS Clinical Research Unit and also the co-author of the study was instrumental in gathering human macrophages for the study.

Since our study utilized lung immune cells from healthy volunteers, we have confidence that our findings are relevant to human health.”

Stavros Garantziotis, Study Co-Author and Medical Director, Clinical Research Unit, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Source:

Journal reference:

Li, H., et al. (2021) sEH promotes macrophage phagocytosis and lung clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi.org/10.1172/JCI129679.