In the fruit fly Drosophila, a team led by Maria Leptin discovered that autophagy, a stress response process in cells, plays a significant role in wound repair: The protein complex TORC1 initiates and regulates the process of autophagy after a wound heals.

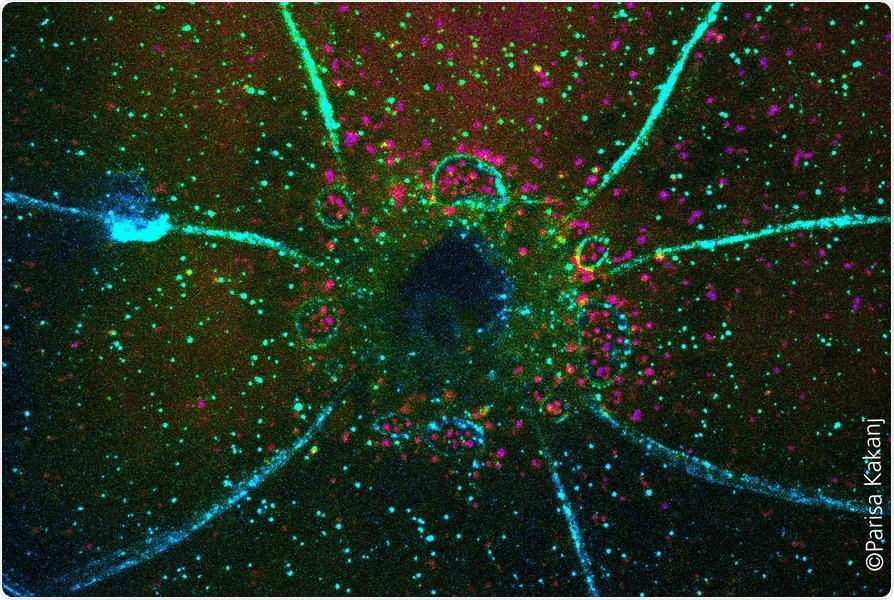

Closing of a wound in Drosophila larva. Membranes are marked in blue and autophagic vesicles in magenta. Image Credit: University of Cologne

This is the first indication that autophagy regulates the production of syncytia, a recently identified function of autophagy (multinucleated cells). While syncytia are created during the formation of muscles and the placenta, their importance in wound repair and autophagy participation are major breakthroughs.

The study has been published in The EMBO Journal.

From yeast to humans, autophagy is a cellular recycling system that has been preserved throughout evolution. Small bubbles within the cell called autophagic vesicles recognize, absorb, and digest invaders like bacteria and viruses, as well as the cell’s own stuff like protein clumps. The material is recycled, giving raw materials to the cell under adverse circumstances.

When correct cellular activity degrades and toxic products gather in organs due to aging, illness, or disease, autophagy function is critical in restoring health. Autophagy malfunction, in turn, raises the risk of neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, as well as cancer and infections.

The role of autophagy in wound healing and the healthy and uninjured epidermis (skin) of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster was explored in the new research by scientists from the CECAD Cluster of Excellence for Aging Research, the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC), and the Institute of Genetics (all at the University of Cologne).

Autophagy did not consume viruses or bacteria in the process described here; instead, it digested the cell’s own cell membrane, causing cell borders to dissolve and a giant cell with numerous nuclei to arise.

Autophagy is boosted in the cells surrounding the wound, according to the researchers. This causes the membranes that link the cells to selectively break down. A huge, multinucleated cell (syncytium) eventually forms.

When we genetically triggered autophagy in healthy, uninjured skin, we again observed the same phenomenon: the membrane between adjacent cells is lost and large patches of multinucleated syncytia form throughout the epidermis.”

Parisa Kakanj, Study First Author, University of Cologne

“It is surprising that the formation of syncytia, which we already know to occur in the formation of some organs such as muscles or placenta, also occurs in wound healing. The role of autophagy in this may also be important for our understanding of disease mechanisms, since multinuclear cells are also found in tumors and infected tissues,” Kakanj added.

The creation of a syncytium has been established in previous studies of muscle and placenta development to provide mechanical integrity and a robust barrier function to protect tissues from infections. It is unclear whether the mechanism has similar characteristics in wound healing. Future research will be conducted on this topic.

The autophagic vesicles interacted with the cell’s lateral plasma membrane in both the healthy, unwounded epidermis and the cells around the wound, according to the researchers.

The appropriate operation of the TORC1 protein complex, which has a vital regulatory role in cell metabolism and also regulates autophagy, is critical in this scenario to prevent autophagy from destroying the epidermis. The team believes that the lateral plasma membrane is a possible source of autophagic vesicles based on these and other findings.

Autophagy is a double-edged sword, the precise extent and spatiotemporal activity of which determines whether it is useful or problematic. To be able to use the beneficial side of autophagy for prevention and therapy, it is even more important to understand how autophagy is activated and how autophagic vesicles are formed.”

Dr Maria Leptin, Professor, Institute for Genetics, University of Cologne

Source:

Journal reference:

Kakanj, P., et al. (2022) Autophagy–mediated plasma membrane removal promotes the formation of epithelial syncytia. The EMBO Journal. doi.org/10.15252/embj.2021109992.