Cells must divide many times before a new plant can grow from seed. Daughter cells can perform different tasks and have different sizes. Prof. Dr Ralf Reski and Dr Elena Kozgunova of the University of Freiburg are investigating how plants decide the plane of cell division in this process known as mitosis in collaboration with Prof. Dr Gohta Goshima of Nagoya University.

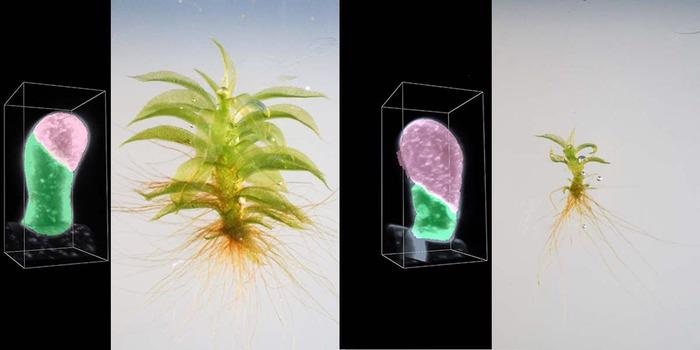

Disturbed cell division in the moss mutant affects plant growth (right) compared to wildtype moss (left). Image Credit: Elena Kozgunova.

Disturbed cell division in the moss mutant affects plant growth (right) compared to wildtype moss (left). Image Credit: Elena Kozgunova.

Researchers discovered how the mitotic machinery is located in the plant cell by working with Physcomitrella, a moss plant.

Using moss cells we were able to observe an unexpected process that is important for the position of the cell division site in plants. The process could be far more similar to animal cell division than previously thought.”

Dr Ralf Reski, Professor, Plant Biotechnology, Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg

Reski of the CIBSS cluster of excellence offers comments on the results of a study, which were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Microtubules, a dynamic network of protein filaments, form a mitotic spindle that pulls chromosomes apart and divides them into two daughter cells when cells divide. Plants and animals vary in this regard: once the spindle is produced, it remains placed in plant cells. During cell division in animal cells, the spindle moves.

When it comes to rest, the cells divide. Moss cells are unique in that during mitosis, they do not develop a belt of microtubules and actin filaments, which are both components of the cytoskeleton. This “preprophase band” (PPB) was formerly considered to regulate where the spindles originate and where they are localized in plants.

But why is the mitotic spindle static in moss cells like in other plants even though there is no preprophase band?”

Dr Elena Kozgunova, Study Lead Author and Professor, Plant Biotechnology, Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg

In Reski’s laboratory, Kozgunova holds a Humboldt-Bayer research scholarship.

Mobile spindles previously unknown in plants

To solve this challenge, the researchers used molecular biology techniques, deleting five genes from spreading earth moss (Physcomitrella) plants. The researchers recognized they looked like an animal gene for a molecule essential in mitosis: the protein TPX2 is involved in animal mitotic spindle formation.

The researchers discovered mitosis in moss plants lacking the TPX2 genes under the microscope. Scientists were surprised to see that the spindles in these cells migrated during cell division in gametophores, which are leafy shoots. “Spindle movement had never been documented before in plant cells,” says Kozgunova. Such cells divided irregularly, resulting in malformations as the plant grew.

Tug-of-war in the cytoskeleton

The researchers next manipulated the cells’ actin skeleton, demonstrating that actin filaments move the mitotic spindle.

It’s a kind of tug-of-war between microtubules and actin that positions the mitotic spindle in the cell. It appears to be similar to the processes in animal cells.”

Dr Ralf Reski, Professor, Plant Biotechnology and Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg

In animal cells, actin filaments are also necessary for spindle transport. These discoveries are assisting researchers in determining which signals influence cell destiny throughout development. Scientists believe that by doing so, experts can have a better knowledge of plant growth and, as a result, be able to affect it.

The recordings of cell division were made at the University of Freiburg’s Life Imaging Centre, a core facility of the CIBSS-Centre for Integrative Biological Signaling Studies Cluster of Excellence.

Source:

Journal reference:

Kozgunova, E., et al. (2022) Spindle motility skews division site determination during asymmetric cell division in Physcomitrella. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30239-1.