According to researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a protein called CDC7, which has long been assumed to play an important role in cell division, may be replaced by another protein called CDK1. Because tumors commonly modify the molecular machinery of cell division to maintain their fast development, the discovery marks a significant advance in cell biology and might lead to novel cancer medicines.

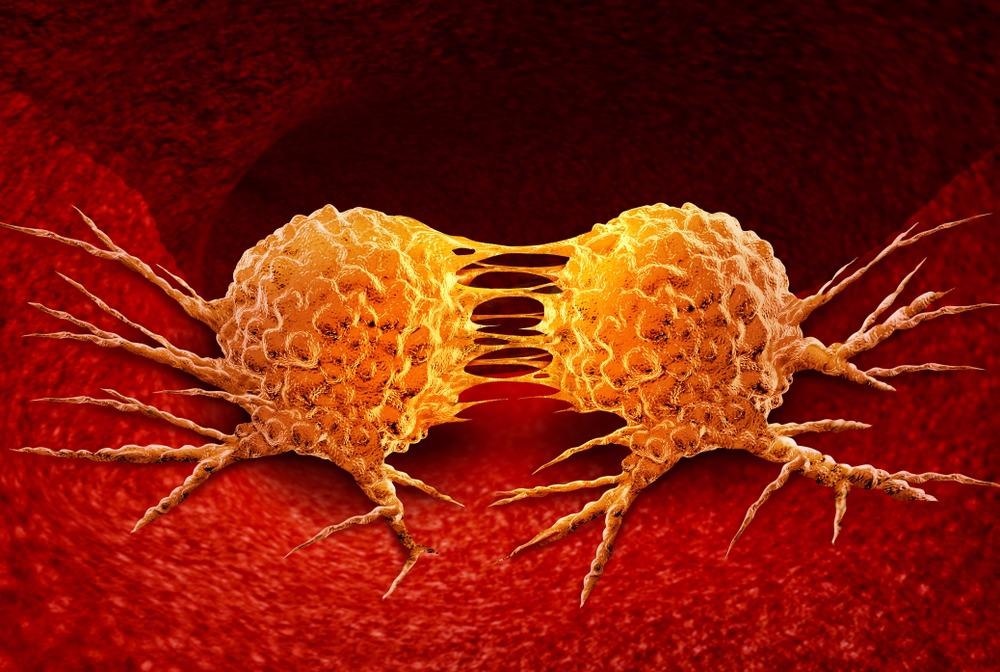

Image Credit: Weill Cornell Medicine.

The study, which was published online on May 4, 2022, in Nature, examined the impact of eliminating CDC7 from a range of mammalian cell types, a tough task. The findings show that targeting CDC7 and CDK1 at the same time might be an effective cancer therapy technique.

This study provides new insight into one of the most important steps in cell division and suggests a new set of targets for future cancer therapies.”

Dr Tobias Meyer, Joseph Hinsey Professor, Cell and Developmental Biology, Weill Cornell Medicine

Meyer is also a member of Weill Cornell Medicine’s Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center.

Dr Peter Sicinski, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and a researcher at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, is the study’s other co-senior author, and the study’s first authors are Dr Jan Suski, a postdoctoral researcher in the Sicinski Lab at Dana-Farber, and Nalin Ratnayeke, a senior graduate student in the Meyer Lab at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The cell division process, often known as the cell cycle, is critical in biology. This process is begun and controlled by a vast number of molecules, including the signaling proteins CDK1, CDK4, CDK6, and CDC7, as scientists have discovered in recent decades.

Much is already recognized about how these proteins orchestrate the start of cell division, and cancer drugs that block both CDK4 and CDK6 are already in the industry. However, the functions of CDK1 and CDC7 in the cell cycle have remained unknown.

CDC7 was assumed to be widely needed for a vital first stage in cell division—moving the cell from the preparation phase of the cell cycle, termed “G1,” into the “S” phase, where the cell replicates its DNA and commits to dividing—based on previous findings mostly in yeast cells.

The researchers employed several novel and old protein-removal techniques to achieve a surprise discovery: selectively deleting the mouse version of CDC7 in distinct cell types can halt or stop cell division for a day or two before it restarts.

The researchers discovered that cells in mice, and likely all mammals, compensate for the loss of CDC7 by increasing CDK1 activity, even though CDK1 is physically distinct from CDC7 and was previously assumed to play a completely different role in cell division.

The results shed light on the cell cycle’s complicated molecular orchestration and suggest that inhibiting both CDC7 and CDK1 at the same time might be a strong new cancer therapy. The researchers are now trying to figure out how the many molecular players in the cell cycle interact.

This work highlights the surprising fact that cells can sometime achieve redundancy for a given function with two very different classes of protein—not just with two closely related proteins as we’re used to seeing.”

Dr Tobias Meyer, Joseph Hinsey Professor, Cell and Developmental Biology, Weill Cornell Medicine

Source:

Journal reference:

Suski, J. M., et al. (2022) CDC7-independent G1/S transition revealed by targeted protein degradation. Nature. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04698-x.