According to a recent study by University of British Columbia (UBC) scientists, even the tiniest marine invertebrates—some slightly larger than single-celled protists—are host to unique and diverse microbial communities or microbiomes.

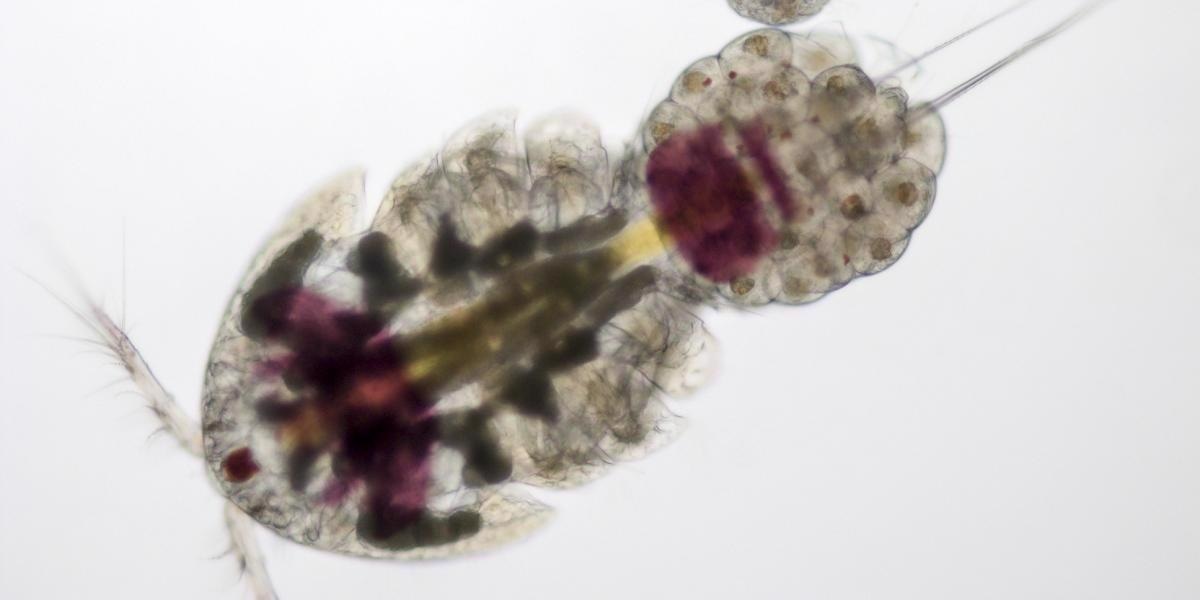

Harpacticoid copepod (Arthropoda, Crustacea) from macroalgae in Calvert Island, carrying a clutch of eggs. Image Credit: University of British Columbia.

Harpacticoid copepod (Arthropoda, Crustacea) from macroalgae in Calvert Island, carrying a clutch of eggs. Image Credit: University of British Columbia.

The study emphasizes that microbiomes exist in a wide variety of animals, just like they do in humans. More surprisingly, there is no link between how closely most animals are related and how identical their microbiomes are—a finding that was generally predicted based on research on humans, bigger mammals, and insects.

This says a lot about how microbiomes originated and how they evolve today. People might intuitively think the purpose of a microbiome is to be of benefit to the host animal, and that they co-evolve together. But the bacteria could care less about helping the animal host—they have their own agenda.”

Dr Patrick Keeling, Study Senior Author, Evolutionary Microbiologist, University of British Columbia

“Most animals harbor a community of bacteria that are simply good at living in animals. From this ‘professional guild’ of animal specialists likely evolved the more elaborate, co-evolving microbiomes that are well studied in humans and insects. But as we looked at a broader set of smaller marine animals, it became clear that the microbiomes of bigger creatures are likely exceptions, not the rule,” Dr Keeling adds.

This study was published in the journal Nature Microbiology.

The microbiomes of the tiny creatures differed from those of the surrounding environment, and even from those of closely related invertebrates, according to the researchers.

Digging into the microbiomes of marine invertebrates

Dr Keeling and coworkers sequenced the microbiomes of 1,037 animals from 21 phyla, which covers the majority of animals, in what may be the largest research of its type. Annelida (ringed worms), Arthropoda (the biggest phylum in the animal world), and Nematoda (a phylum of unsegmented, cylindrical worms) were among the animal lineages sampled more extensively.

In British Columbia, Canada, and Curaçao, a Dutch Caribbean island, the researchers also gathered samples from the surrounding environments.

Studying such a broad range of animals was crucial–in a smaller study a number of prevalent bacteria may have been mistaken for host-specific symbionts. We found most bacteria were only present in some individuals of a species, and most of these were also present other host species in the same environment.”

Dr Corey Holt, Study First Author and Postdoctoral Fellow, University of British Columbia

Exploring evolutionary time scales

This survey was designed to look at an incredibly broad diversity of animals. The next step is to take a few of the more interesting groups and dig deeper to see how microbiomes evolved within that group to clarify the time scales at which different evolutionary processes are operating.”

Dr Patrick Keeling, Study Senior Author, Evolutionary Microbiologist, University of British Columbia

Researchers from UBC, the Hakai Institute, the University of Copenhagen, the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, the Polish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and the University of Hamburg were part of the multinational collaboration.

Source:

Journal reference:

Boscaro, V., et al. (2022) Microbiomes of microscopic marine invertebrates do not reveal signatures of phylosymbiosis. Nature Microbiology. doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01125-9.