Reviewed by Danielle Ellis, B.Sc.Jun 6 2022

Over 670,000 people in Europe become ill each year as a result of pathogenic bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics, and 33,000 people die as a result of the diseases they cause. Pathogens that are resistant to multiple antibiotics at the same time are particularly dangerous.

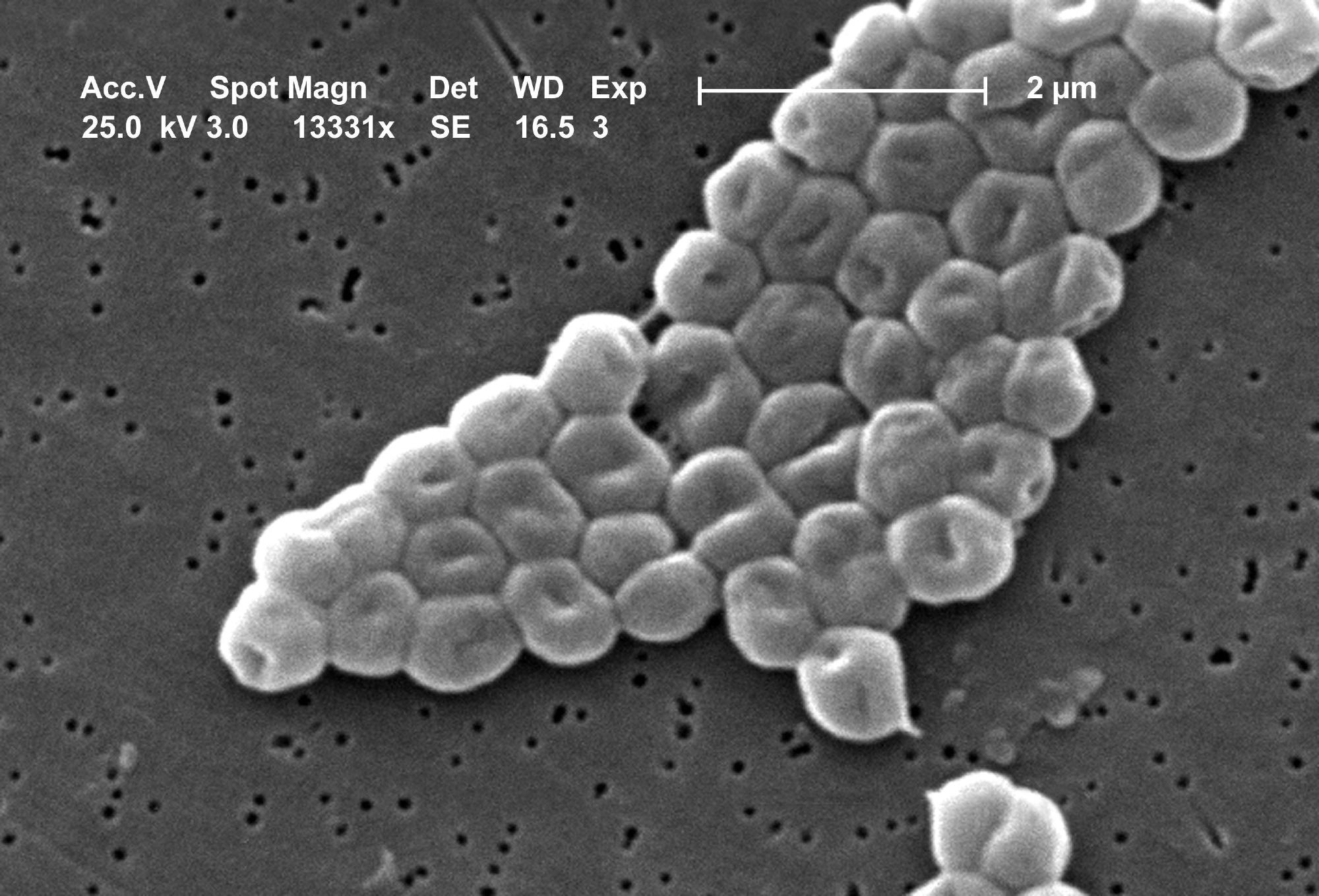

Scanning electron micrograph of a cluster of Gram-negative, immobile bacteria of the Acinetobacter baumannii species. Image Credit: Janice Carr.

Scanning electron micrograph of a cluster of Gram-negative, immobile bacteria of the Acinetobacter baumannii species. Image Credit: Janice Carr.

The bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii is one of them, and it is now feared as a “hospital superbug”. It is responsible for up to 5% of all hospital-acquired bacterial infections.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), A. baumannii is at the top of a list of candidates for which new therapies must be developed. This is due to the pathogen’s flexible genome, which allows it to effortlessly pick up new antibiotic resistance. Simultaneously, infections are emerging outside of the hospital environment in greater numbers, and they are progressing at a faster rate.

However, understanding which properties make Acinetobacter baumannii and its human pathogenic relatives, grouped in the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii (ACB) complex, pathogens are a prerequisite for the development of new therapeutic approaches.

A group headed by bioinformatician Professor Ingo Ebersberger from Goethe University Frankfurt/ LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (LOEWE-TBG) has recently reached a breakthrough in this understanding.

Members of the German Research Foundation’s Research Unit 2251, as well as other national and international partners, including scientists from Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, USA, make up the team.

The researchers relied on the fact that many members of the Acinetobacter genus are harmless environmental bacteria that thrive in water or on plants or animals for their research. Thousands of complete genome sequences of both these and pathogenic Acinetobacter strains are available in public databases.

The scientists were able to methodically filter out differences between pathogenic and harmless bacteria by comparing these genomes. Because the frequency of individual genes was inconclusive, Ebersberger and his coworkers focused on gene clusters, which are groups of adjacent genes that have managed to remain stable over time and may form a functional unit.

Of these evolutionarily stable gene clusters, we identified 150 that are present in pathogenic Acinetobacter strains and rare or absent in their non-pathogenic relatives. It is highly probable that these gene clusters benefit the pathogens' survival in the human host.”

Ingo Ebersberger, Professor, LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics, Goethe University Frankfurt

Pathogens’ capacity to form protective biofilms and effectively absorb micronutrients like iron and zinc is one of their most important traits. Indeed, the scientists found that the ACB group’s uptake systems were a reinforcement of an older, more evolved uptake mechanism.

The fact that pathogens have tapped a unique source of energy is especially interesting. They can break down the carbohydrate kynurenine, which is produced by humans and functions as a messenger substance that controls the innate immune system.

In this way, the bacteria appear to kill two birds with one stone. On one hand, breaking down kynurenine provides them with energy, and on the other, they may be able to use it to de-regulate the immune response of the host.

Our work is a milestone in understanding what's different about pathogenic Acinetobacter baumannii. Our data are of such a high resolution that we can even look at the situation in individual strains. This knowledge can now be used to develop specific therapies against which, with all probability, resistance does not yet exist.”

Ingo Ebersberger, Professor, LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics, Goethe University Frankfurt

Source:

Journal reference:

Djahanschiri, B., et al. (2022) Evolutionarily stable gene clusters shed light on the common grounds of pathogenicity in the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex. PLOS Genetics. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1010020.