To create a new class of antibiotics, investigators from University Hospital Frankfurt and Goethe University Frankfurt have figured out how bacteria adhere to host cells.

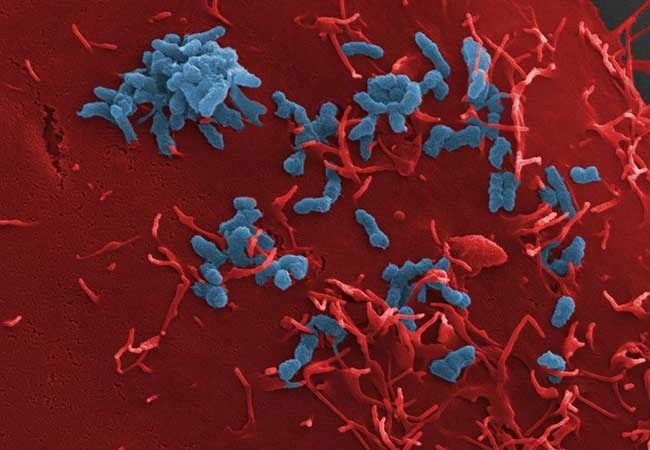

Adhesion of Bartonella henselae (blue) to human blood vessel cells (red). The bacterium’s adhesion to the host cells could be blocked with the help of what are known as “anti-ligands”. Image Credit: van Belkum, et al. (2021) Diagnostics.

Adhesion of Bartonella henselae (blue) to human blood vessel cells (red). The bacterium’s adhesion to the host cells could be blocked with the help of what are known as “anti-ligands”. Image Credit: van Belkum, et al. (2021) Diagnostics.

The first and most important step in the development of infectious diseases is always the adhesion of bacteria to host cells. The goal of the infectious pathogens’ adhesion is to first colonize the host organism, which in this case is the human body, and then to start an infection that, in the worst case scenario, could be fatal.

Discovering therapeutic alternatives that obstruct this vital interaction in the earliest stage of infection requires an accurate understanding of how the bacteria adhere to host cells.

Critical interaction with the human protein fibronectin

Researchers from University Hospital Frankfurt and Goethe University Frankfurt have now used the human-pathogenic bacterium Bartonella henselae to precisely elucidate the mechanism of bacterial adhesion. The “cat-scratch disease,” which is contracted from cats to humans, is brought on by this pathogen.

Using a combination of in vitro adhesion tests and high-throughput proteomics, the bacterial adhesion mechanism was elucidated in an international collaborative project directed by the Frankfurt research group led by Professor Volkhard Kempf. The study of all the proteins found in a cell or a complex organism is known as proteomics.

The researchers have revealed a crucial mechanism: the interaction of a specific class of adhesins, known as “trimeric autotransporter adhesins,” with fibronectin, a protein frequently found in human tissue, is what causes bacteria to adhere to host cells.

Adhesins are components on bacteria’s surface that help the pathogen stick to the biological structures of the host. Numerous other human-pathogenic bacteria, like the multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, which the World Health Organization (WHO) has designated as the top priority for research into new antibiotics, also contain homologs of the adhesin that has been identified as pivotal.

Sophisticated protein analytics were being used to visualize the precise sites of protein interaction. It was also demonstrated that experimental blocking of these processes virtually eliminates bacterial adhesion. In the continually expanding field of multi-resistant bacteria, therapeutic strategies that work to eliminate bacterial adhesion in this way could be a hopeful treatment alternative as a new class of antibiotics (known as “anti-ligands”).

Source:

Journal reference:

Vaca, D. J., et al. (2022) Interaction of Bartonella henselae with Fibronectin Represents the Molecular Basis for Adhesion to Host Cells. Microbiology Spectrum. doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00598-22.