Reviewed by Danielle Ellis, B.Sc.Sep 14 2022

By helping with digestion, supplying nutrients and metabolites, and collaborating with the immune system to ward off pathogens, gut bacteria have a significant impact on health. However, some gut bacteria have been linked to the development of cancers of the gut and related organs.

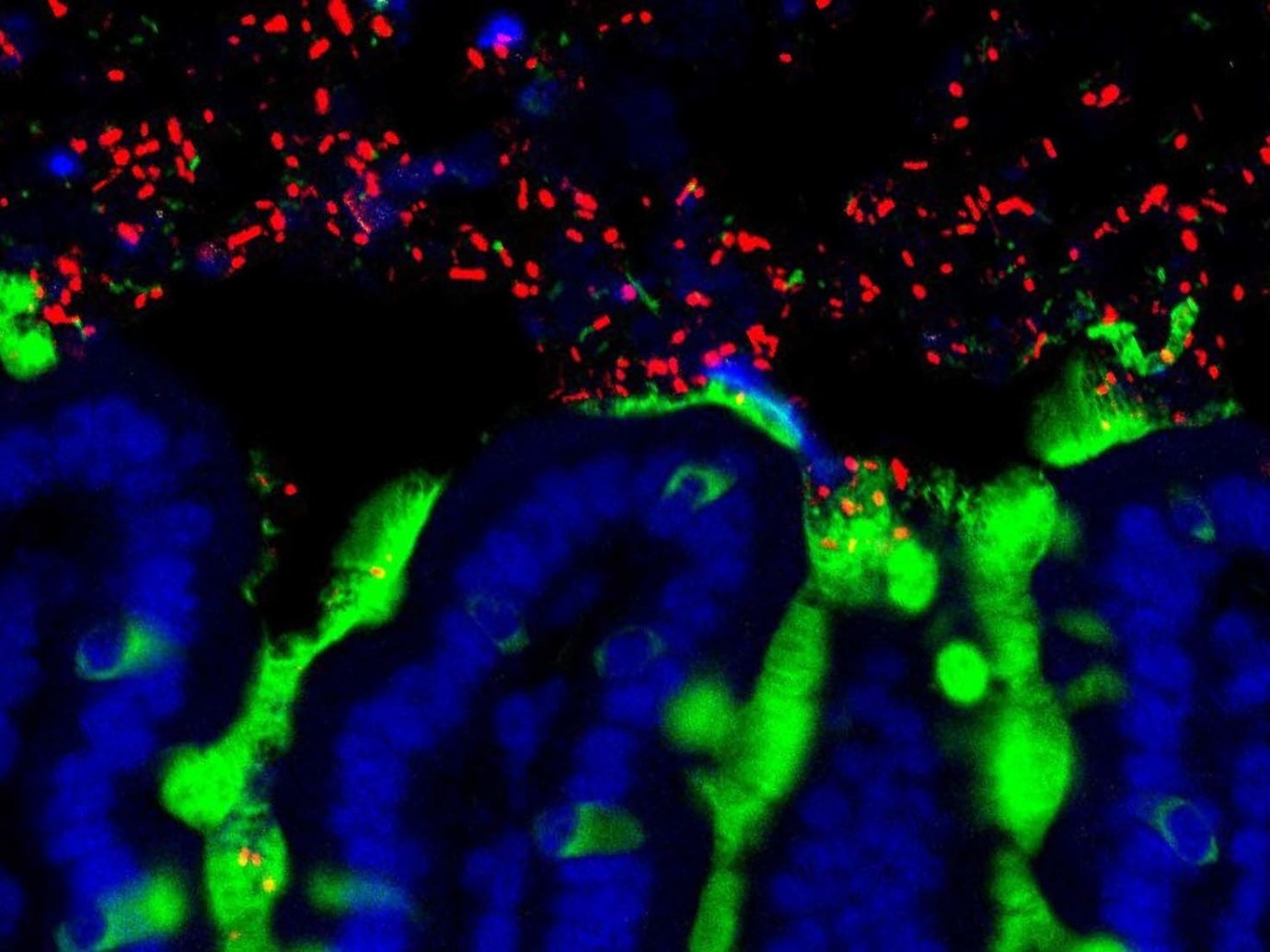

Commensal bacteria (red) reside amongst the mucus (green) and epithelial cells (blue) of a mouse small intestine. Image Credit: University of Chicago

Commensal bacteria (red) reside amongst the mucus (green) and epithelial cells (blue) of a mouse small intestine. Image Credit: University of Chicago

According to a recent study by researchers from the University of Chicago, certain commensal bacteria block the animal’s adaptive anti-tumor immune response, which aids in the development of leukemia brought on by the murine leukemia virus (MuLV).

Three genes known as negative immune regulators are produced more frequently or are increased in the presence of commensal bacteria and the virus in mice. This suppresses the immune response that would otherwise kill the tumor cells.

Two of these three unfavorable immune regulators have also been linked to a poor prognosis in various types of cancer in humans.

These two negative immune regulators have been really well documented to be poor prognostic factors in some human cancers, but nobody knew why. Using a mouse model of leukemia, we found that the bacteria contribute to upregulation of these negative immune regulators, allowing developing tumors to escape recognition by the immune system.”

Tatyana Golovkina, Study Senior Author and Professor, Microbiology, University of Chicago

Cell Reports published the study’s findings on September 13th, 2022.

Typically, it is believed that cancer-forming spontaneous mutations lead cells to proliferate and reproduce uncontrollably. Peyton Rous, a pathologist, extracted a malignant tumor sample from a chicken in 1910 and put it into a healthy bird, which also developed cancer.

His discovery was disregarded at the time, but researchers later learned that a retrovirus was responsible for the cancer’s transmission. Further investigation led to the identification of multiple retroviruses that cause numerous types of cancers as a result of this discovery.

Some retroviruses that cause cancer employ the microorganisms in the gut to spread and multiply. For instance, Golovkina and her team discovered in a 2011 study that a virus that results in mammary tumors in mice relies on gut bacteria, allowing the virus to thwart the immune system’s ability to identify and eliminate infected cells.

As a result, the bacteria aid in the virus’ replication, which leads to the growth of tumors.

The purpose of the current research was to determine whether commensal bacteria had any further effects on the growth of a virus-induced malignancy beyond aiding in its multiplication.

They employed specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice, which do not have any pathogenic microbes that could cause disease but do have common commensal microbes, such as bacteria that ordinarily inhabit the gut, and germ-free (GF) mice, which had been bred in a special facility, so they had no microbes.

The murine leukemia virus (MuLV) infected both GF and SPF mice. Both strains of mice were equally infected and reproduced by the virus, but only SPF mice developed high-frequency tumors.

Cancer cells that have been brought on by a virus all produce viral antigens, or chemicals, which identify them as alien to the host and leave them vulnerable to immune attack. Golovkina’s team looked for a microbe-dependent immune evasion mechanism that allowed virally generated cancer cells to persist in the host since they needed to be shielded from the immune system’s attack to continue replicating.

With specially created immunodeficient mice that did not have an adaptive immune system, the researchers conducted a number of investigations on them. These mice experienced the same frequency of tumor development when exposed to the virus in the germ-free environment as immunosufficient SPF mice with healthy immune systems.

Therefore, microorganisms that were later identified as commensal bacteria were preventing the anti-tumor immune response from working.

The researchers subsequently discovered that three genes known as negative immune regulators were triggered in infected mice by commensal bacteria. In contrast to their usual function, which is to shut down the immune system once it has dealt with a disease, these genes, in this circumstance, prevented the immune system from attacking cancer cells.

Serpinb9b and Rnf128 are two of the three increased negative immune regulators, and both have been linked to a poor prognosis in humans with various spontaneous malignancies. Golovkina and her team are pursuing further study into why this immune dampening ability only kicks in when both a virus and bacteria are present since not all commensal bacteria have tumor-promoting qualities.

Golovkina added, “Now we have to figure out what is so special about bacteria which have these properties.”

Source:

Journal references:

- Spring, J., et al (2022) Gut commensal bacteria enhance pathogenesis of a tumorigenic murine retrovirus. Cell Reports. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111341

- Kane, M., et al (2022) Successful Transmission of a Retrovirus Depends on the Commensal Microbiota. Science. doi:10.1126/science.1210718