According to preliminary findings from an ongoing, prospective study headed by Cedars-Sinai researchers, one type of bacteria seen in the gut might contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes, while another might guard against the condition.

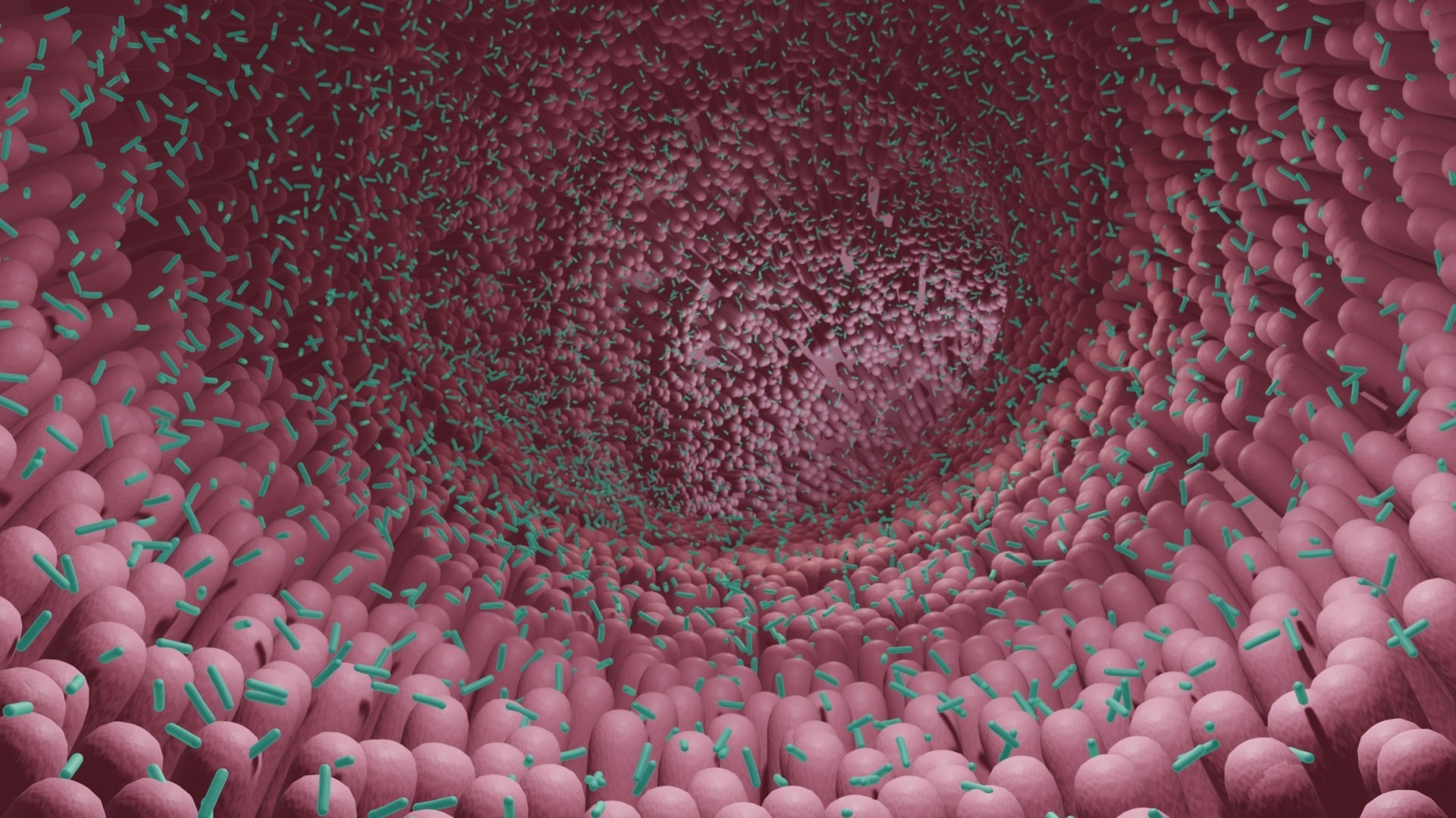

For years, investigators have sought to understand why people develop diabetes by studying the composition of the microbiome, which is a collection of microorganisms that include fungi, bacteria, and viruses that live in the digestive tract. Image Credit: Getty.

For years, investigators have sought to understand why people develop diabetes by studying the composition of the microbiome, which is a collection of microorganisms that include fungi, bacteria, and viruses that live in the digestive tract. Image Credit: Getty.

The research, published in the peer-reviewed journal Diabetes, discovered that individuals who had elevated levels of the bacterium Coprococcus had higher insulin sensitivity, whereas those with higher levels of the bacterium Flavonifractor had poorer insulin sensitivity.

For years, researchers have worked to figure out why individuals develop diabetes by researching the composition of the microbiome, which is a collection of microbes that live in the digestive tract and include fungi, bacteria, and viruses.

Medication and food are known to have an impact on the microbiota. According to research, individuals who do not absorb insulin adequately have fewer amounts of a certain type of bacteria that produces a fatty acid called butyrate.

Mark Goodarzi, MD, PhD, Director of Cedars-Endocrine Sinai’s Genetics Laboratory, is directing an ongoing study that monitors people at risk for diabetes to see if those with lower numbers of these bacteria get the condition.

The big question we're hoping to address is: Did the microbiome differences cause the diabetes, or did the diabetes cause the microbiome differences?”

Mark Goodarzi, Study Senior Author and Director, Genetics Laboratory, Cedars-Endocrine Sinai

Goodarzi is the principal investigator of the multicenter study called Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study (MILES).

MILES investigators have been gathering data from participating Black and non-Hispanic white adults aged 40 to 80 years old since 2018. Earlier cohort research from the MILES trial discovered that cesarean birth is related to an increased risk of acquiring prediabetes and diabetes.

Investigators evaluated data from 352 participants without known diabetes recruited from the Wake Forest Baptist Health System in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the latest research to come out of this continuing investigation.

The study's participants were required to attend three clinic appointments and provide stool samples prior to the visits. The data acquired during the initial visit was examined by the investigators.

They used genetic sequencing on stool samples, for example, to analyze the individuals’ microbiomes and especially look for bacteria that have previously been linked to insulin resistance. Each participant also completed a food questionnaire and an oral glucose tolerance test to measure their capacity to handle glucose.

The researchers discovered that 28 patients had oral glucose tolerance results that satisfied the criteria for diabetes. They also discovered that 135 patients had prediabetes, a condition in which blood sugar levels are higher than usual but not high enough to qualify as diabetes.

The researchers looked for links between 36 butyrate-producing bacteria present in stool samples and a person’s capability to maintain appropriate insulin levels. They accounted for factors that could also increase a person’s diabetes risk, such as age, sex, BMI, and race. Coprococcus and related bacteria produced a bacterial network that improved insulin sensitivity.

Despite being a butyrate generator, Flavonifractor has been linked to insulin resistance; previous research has identified increased levels of Flavonifractor in the stool of diabetes patients.

Researchers are still studying samples from individuals who took part in this trial to determine how insulin production and microbiome makeup change over time. They also intend to investigate how nutrition may influence the bacterial balance of the microbiome.

However, Goodarzi stressed that it is too early to tell how people might adjust their microbiome to lower their diabetes risk.

Goodarzi, who is also the Eris M. Field Chair in Diabetes Research at Cedars-Sinai added, “As far as the idea of taking probiotics, that would really be somewhat experimental. We need more research to identify the specific bacteria that we need to be modulating to prevent or treat diabetes, but it's coming, probably in the next five to 10 years.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Cui, J., et al. (2022) Butyrate-Producing Bacteria and Insulin Homeostasis: The Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study (MILES). Diabetes. doi.org/10.2337/db22-0168.