Cell division is the process through which the majority of cells in the bodies of living beings duplicate their contents and physically split into new cells. Yet, the germ cells that develop into eggs or sperm do not completely split into many animals. They connect and remain linked through small bridges known as ring canals.

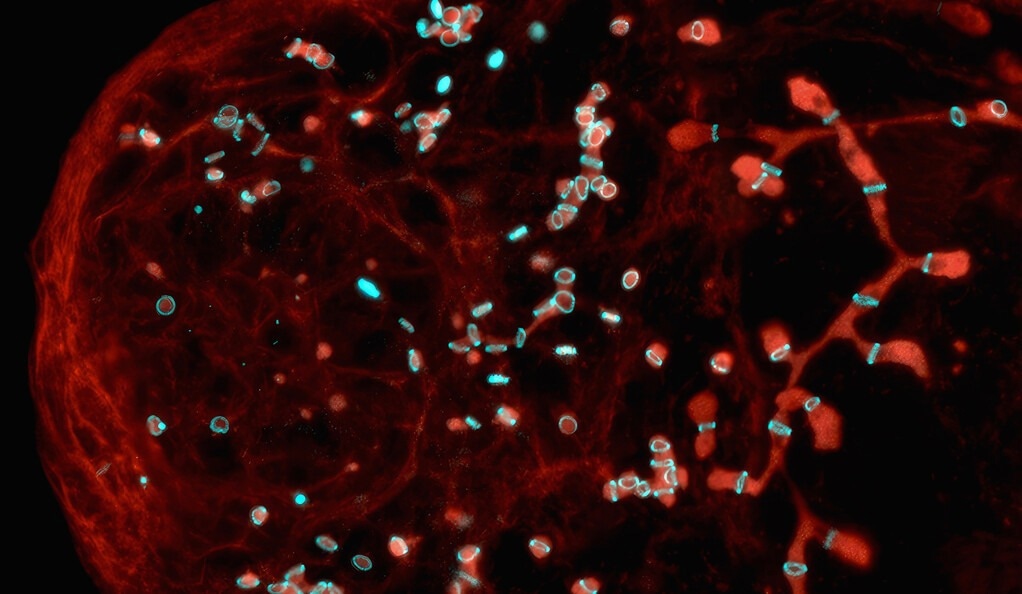

Fruit fly sperm cells develop in clusters connected by intercellular bridges called ring canals (in blue). Image Credit: Kari Price

Fruit fly sperm cells develop in clusters connected by intercellular bridges called ring canals (in blue). Image Credit: Kari Price

In a recent study, Yale researchers explain for the first time how fruit fly germ cells create these ring canals. They believe that this discovery will shed new light on a prevalent aspect of development and also diseases where cell division is interrupted.

Developmental Cell reported the findings on March 9th, 2023.

From simpler organisms like sponges and fruit flies to more sophisticated creatures like mice and humans, scientists have noticed ring canals in male and female germ cells across a wide range of species. Furthermore, ring canals appear to be crucial for cell development, even if their function is not entirely known, according to the researchers.

For example, in female fruit flies, ring canals are required to grow a functional oocyte, a developing egg cell. If you block ring canals, female flies grow tiny, little eggs and can’t reproduce.”

Lynn Cooley, PhD, Study Senior Author and C.N.H. Long Professor, Genetics, School of Medicine, Yale University

However, it is still unknown how ring canals develop.

The researchers employed a live imaging strategy to better comprehend how they developed. They used fluorescent molecules to identify the numerous ring canal proteins in fruit flies, and then they used a microscope to monitor what those proteins performed over time in the germ cells of both males and females.

When we did this, we saw the first signs of a structure we call the germline midbody.”

Kari Price, Study Lead Author and Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Medicine, Yale University

A structure called the midbody develops during cell division, and one of its functions is to draw in the molecules required to separate cells at the process’ end. According to the study, the midbody that was exceptionally large appeared in fruit fly germ cells, lingered for 20 to 30 minutes, and then underwent radical remodeling to transform from a sphere into a ring instead of commencing full separation.

The stable ring canals that connected the sibling cells eventually developed from these midbody rings.

This transition from the midbody to the ring canal was also discovered by researchers in mice and freshwater polyps, indicating that it is an evolutionary trait that has persisted.

Cooley added, “To see this solid, little object turn into a ring—that had not been observed in intact living cells before. It was, to us, very striking; it was an ‘a-ha moment.’ And it would have been tough to discover this in anything other than fruit flies. This study is such a great example of how model systems like fruit flies are essential for understanding fundamental mechanisms of development.”

The new discovery, according to the researchers, not only represents a significant step towards understanding the function and development of ring canals but could also offer insight into diseases such as colorectal cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and some immunodeficiency syndromes that are associated with incomplete cell division.

The results could potentially aid studies into the origins of evolution.

Cooley further stated, “There are very primitive creatures that, when they divide, make colonies that are attached with persistent cellular bridges, much like what we see with germ cells. Maybe this way of keeping sibling cells connected in a colony or cluster is the beginning of how multicellular evolution occurred, and maybe germ cells are a reflection of that.”

In the future, researchers want to figure out what causes germ cells to stay attached.

Price concluded, “In this current study we saw that blocking an enzyme called Citron kinase delayed or prevented the midbody-to-ring canal transition. So we’re looking at Citron kinase more deeply to see what exactly it’s doing in these cells during division.”