Reviewed by Danielle Ellis, B.Sc.Jun 19 2023

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) introduces a copy of its DNA into human immune cells as part of its life cycle. Some of these newly infected immune cells can subsequently enter an inactive, latent state for an extended length of time, which is known as HIV latency.

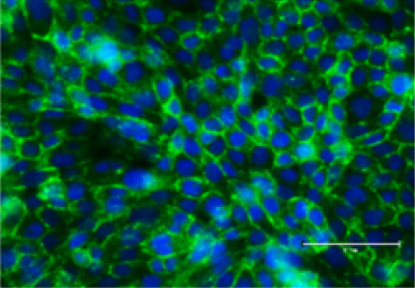

Microglia isolated from ART-suppressed, SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Image Credit: UNC School of Medicine

Microglia isolated from ART-suppressed, SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Image Credit: UNC School of Medicine

Although contemporary antiretroviral therapy (ART) can successfully prevent the virus from multiplying further, it cannot remove latent HIV. If treatment is ever interrupted, the virus might reactivate from dormancy and restart the development of HIV infection to AIDS.

Researchers from the UNC School of Medicine, the University of California San Diego, Emory University, and the University of Pennsylvania have been looking for where these latent cells are hidden in the body. Microglial cells, which are specialized immune cells with a decade-long lifespan in the brain, can serve as a persistent viral reservoir for latent HIV, according to new research published in The Journal of Clinical Investigations.

We now know that microglial cells serve as a persistent brain reservoir. This had been suspected in the past, but proof in humans was lacking. Our method for isolating viable brain cells provides a new framework for future studies on reservoirs of the central nervous system, and, ultimately, efforts towards the eradication of HIV.”

Yuyang Tang, Study First Author and Assistant Professor, Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, UNC School of Medicine

Yuyang Tang is also a member of the UNC HIV Cure Center

Latent HIV

HIV is a difficult virus to research. During infection, the virus primarily targets CD4+ lymphocytes, which are the major coordinators of the immune response. The virus kills enough CD4+ cells over time to develop immunodeficiency.

Earlier studies have demonstrated that latent HIV can lurk within a few of the body’s and bloodstream’s surviving CD4+ T cells. Other viral reservoirs, however, have been suspected of hiding within the central nervous system (CNS) of HIV patients receiving effective ART.

Unlike peripheral blood cells, accessing and analyzing brain tissues for the research of HIV reservoirs is incredibly difficult. Because these cells cannot be safely sampled in ART patients, the potential viral reservoir in the brain has remained a mystery for many years.

Extracting Pure Brain Tissue

To gain a better knowledge of how to extract and purify viable cells from primate brain tissue, the scientists first analyzed the brains of macaques infected with the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus closely linked to HIV, from Emory University’s Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Physical separation techniques and antibodies were utilized by the researchers to selectively extract cells expressing microglial surface markers. The very pure brain myeloid cells were then extracted and segregated from the CD4+ cells that were moving through the brain tissue.

Using these methods, researchers retrieved samples donated by HIV+ participants in the “The Last Gift” Study at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). As part of this one-of-a-kind and significant initiative, altruistic HIV+ patients on ART but suffering from other terminal illnesses will donate their bodies to the HIV research project.

The samples are from people living with HIV, who are on therapy but facing a fatal disease of some kind. They were willing to not just donate their bodies to science, but also participate in the research program in the months leading up to their death. It’s an extraordinary program that made this critical research possible.”

David Margolis, Study Co-Author and Sarah Kenan Distinguished Professor, Medicine, Microbiology & Immunology, and Epidemiology, University of California, San Diego

Future Projects

Researchers are investigating plans to target this type of reservoir now that they know latent HIV can seek refuge in microglial cells in the brain. Because latent HIV in the brain differs significantly from the virus in the periphery, experts believe it has evolved specific properties to replicate in the brain.

HIV is very smart. Over time, it has evolved to have epigenetic control of its expression, silencing the virus to hide in the brain from immune clearance. We are starting to unravel the unique mechanism that allows latency of HIV in brain microglia.”

Guochun Jiang, Study Senior Author and Assistant Professor, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, UNC School of Medicine

Guochun Jiang is also a member of the UNC HIV Cure Center.

One of the main signaling networks that governs HIV expression elsewhere in the body is NF-κB signaling. HIV enters latency in the peripheral blood when NF-κB signaling is “turned off.”

However, it appears that NF-κB signaling activity has little effect on latent HIV in the brain. Researchers are really not sure why, but if they figure it out, they will be one step closer to understanding how to selectively target and destroy the virus in the brain or peripheral blood. The researchers are attempting to discover the true magnitude of the latent HIV brain reservoir in addition to identifying the inner workings of the brain reservoir.

“It is very hard to know how big the reservoir is. The problem with trying to eradicate HIV is like trying to eradicate cancer. You want to be able to get it all, so it won’t come back,” concludes Margolis, who is also the Director of the UNC HIV Cure Center.

Source:

Journal reference:

Tang, Y., et al. (2023). Brain microglia serve as a persistent HIV reservoir despite durable antiretroviral therapy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi.org/10.1172/JCI167417.