In-cell engineering can be a powerful tool for synthesizing functional protein crystals with promising catalytic properties, show researchers at Tokyo Tech. Using genetically modified bacteria as an environmentally friendly synthesis platform, the researchers produced hybrid solid catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. These catalysts exhibit high activity, stability, and durability, highlighting the potential of the proposed innovative approach.

Image Credit: Tokyo Institute of Technology

Protein crystals, like regular crystals, are well-ordered molecular structures with diverse properties and a huge potential for customization. They can assemble naturally from materials found within cells, which not only greatly reduces the synthesis costs but also lessens their environmental impact.

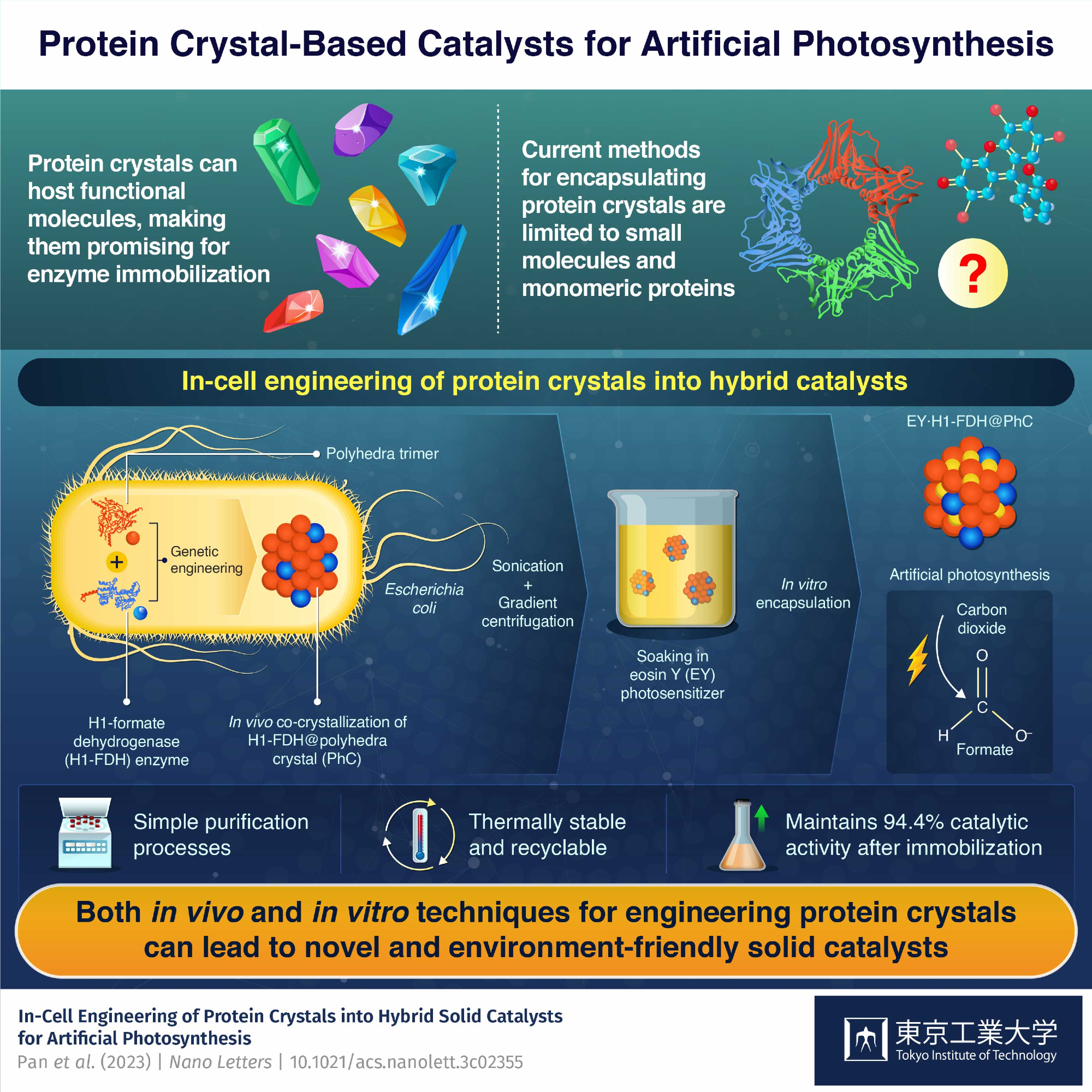

Although protein crystals are promising as catalysts because they can host various functional molecules, current techniques only enable the attachment of small molecules and simple proteins. Thus, it is imperative to find ways to produce protein crystals bearing both natural enzymes and synthetic functional molecules to tap their full potential for enzyme immobilization.

Against this backdrop, a team of researchers from Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) led by Professor Takafumi Ueno has developed an innovative strategy to produce hybrid solid catalysts based on protein crystals. As explained in their paper published in Nano Letters on 12 July 2023, their approach combines in-cell engineering and a simple in vitro process to produce catalysts for artificial photosynthesis.

The building block of the hybrid catalyst is a protein monomer derived from a virus that infects the Bombyx mori silkworm. The researchers introduced the gene that codes for this protein into Escherichia coli bacteria, where the produced monomers formed trimers that, in turn, spontaneously assembled into stable polyhedra crystals (PhCs) by binding to each other through their N-terminal α-helix (H1). Additionally, the researchers introduced a modified version of the formate dehydrogenase (FDH) gene from a species of yeast into the E. coli genome. This gene caused the bacteria to produce FDH enzymes with H1 terminals, leading to the formation of hybrid H1-FDH@PhC crystals within the cells.

The team extracted the hybrid crystals out of the E. coli bacteria through sonication and gradient centrifugation, and soaked them in a solution containing an artificial photosensitizer called eosin Y (EY). As a result, the protein monomers, which had been genetically modified such that their central channel could host an eosin Y molecule, facilitated the stable binding of EY to the hybrid crystal in large quantities.

Through this ingenious process, the team managed to produce highly active, recyclable, and thermally stable EY·H1-FDH@PhC catalysts that can convert carbon dioxide (CO2) into formate (HCOO−) upon exposure to light, mimicking photosynthesis. In addition, they maintained 94.4% of their catalytic activity after immobilization compared to that of the free enzyme. “The conversion efficiency of the proposed hybrid crystal was an order of magnitude higher than that of previously reported compounds for enzymatic artificial photosynthesis based on FDH,” highlights Prof. Ueno. “Moreover, the hybrid PhC remained in the solid protein assembly state after enduring both in vivo and in vitro engineering processes, demonstrating the remarkable crystallizing capacity and strong plasticity of PhCs as encapsulating scaffolds.”

Overall, this study showcases the potential of bioengineering in facilitating the synthesis of complex functional materials.

The combination of in vivo and in vitro techniques for the encapsulation of protein crystals will likely provide an effective and environmentally friendly strategy for research in the areas of nanomaterials and artificial photosynthesis.

Takafumi Ueno, Professor, Tokyo Institute of Technology