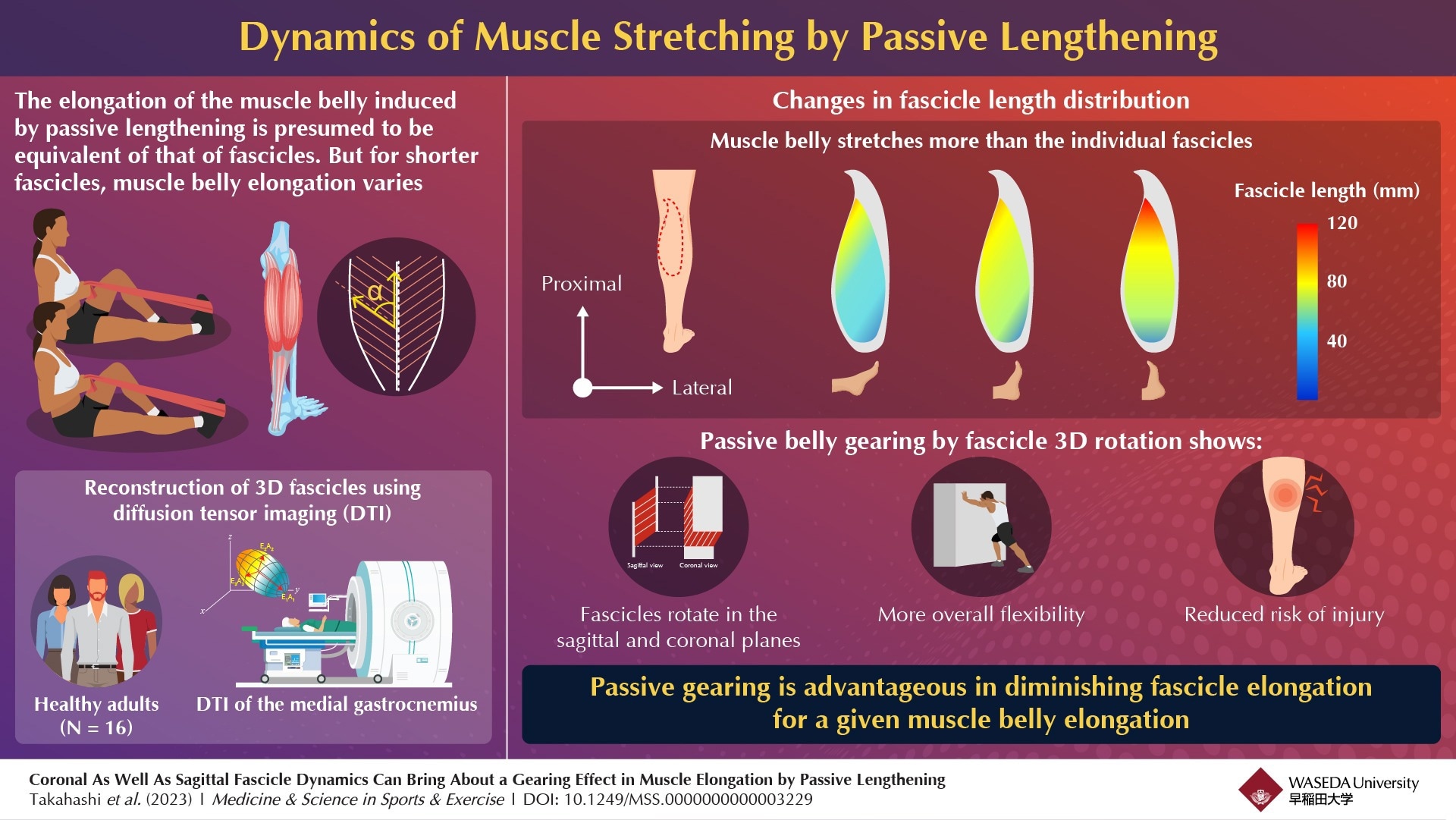

Muscle belly elongation due to passive lengthening is frequently presumed to be equivalent to that of fascicles. However, researchers have now revealed that since the muscle fascicle arrangement is three-dimensional, passive lengthening can lead to fascicle rotation in both the coronal and sagittal planes. This “gearing effect” helps prevent the fibers from overstretching and enhances overall flexibility.

Researchers from Waseda University explored the three-dimensional dynamics of muscle fascicles during stretching and found that passive gearing is beneficial for diminishing fascicle elongation for a given muscle belly. Image Credit: Dr. Yasuo Kawakami from Waseda University

Researchers from Waseda University explored the three-dimensional dynamics of muscle fascicles during stretching and found that passive gearing is beneficial for diminishing fascicle elongation for a given muscle belly. Image Credit: Dr. Yasuo Kawakami from Waseda University

Detailed insights into muscle and tendon movement mechanisms during stretching are essential to improve our overall mobility and flexibility. It is not only important for optimum athletic performance, but also crucial for preventing musculoskeletal injuries. When an individual stretches, 50% to 70% of the elongation is absorbed into the muscle belly, i.e., the fleshy part of the muscle containing most fibers.

However, in skeletal muscles with fascicles, the muscle fibers are shorter than the muscle belly and attach to the tendon at an angle. This angle between the fascicles and the tendon changes in response to the length of the muscle belly through a mechanism known as 'gearing'. However, despite advancements in tissue-imaging technologies, our understanding of these geometrical dynamics has been confined to a 2D perspective.

Against this backdrop, a team of researchers led by Dr. Yasuo Kawakami from Waseda University, including Dr. Katsuki Takahashi from Doshisha University, Dr. Hiroto Shiotani from Waseda University, Dr. Pavlos E. Evangelidis from the University of Exeter, and Dr. Natsuki Sado from the University of Tsukuba embarked on an innovative research project, the findings of which were published in Volume 55, Issue 11 of Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise® in November 2023. Their goal was to better understand the three-dimensional dynamics of fascicles during stretching, particularly in pennate muscles.

The team used diffusion tensor imaging to reconstruct the fascicles of 16 healthy adults in three dimensions. They specifically measured changes in fiber length and angles in both the sagittal and coronal planes during passive ankle dorsiflexion. Dr. Kawakami explains, “The effect is somewhat like what happens upon opening a book. As you open a book, the page angle changes – they fan out – but the pages themselves do not get longer.” Similar to this, as the muscle stretches, the fibers change their angle, allowing the muscle to extend, without any significant change in the length of each fiber.

This gearing mechanism not only contributes to the overall elongation of the muscle but reduces the elongation of individual fascicles at any given time, preventing them from overstretching and getting injured.

These findings challenge and extend our current understanding of how muscles work, and they underscore the value of diving into the finer details of familiar territory, as this can lead to unexpected and intriguing results.”

Dr. Yasuo Kawakami, Waseda University

Comprehensive knowledge of how muscles naturally adapt during stretching can help us develop better techniques and practices in sports training and physical therapy. Additionally, by understanding the limits and capabilities of muscle stretching, we can gain insights into how to train more effectively and safely. This can help prevent injuries and aid in the rehabilitation of muscle-related injuries.

Going forward, the team plans to extend their research to other muscles, each with their own unique structural characteristics to further enhance our understanding of human muscle movement.