Reviewed by Danielle Ellis, B.Sc.Jan 24 2024

In a recent study, the predator-prey connection between two species of lab-grown bacteria was reversed when one species was cultivated at a lower temperature. These results were published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology on January 23rd by Marie Vasse of MIVEGEC, France, and colleagues.

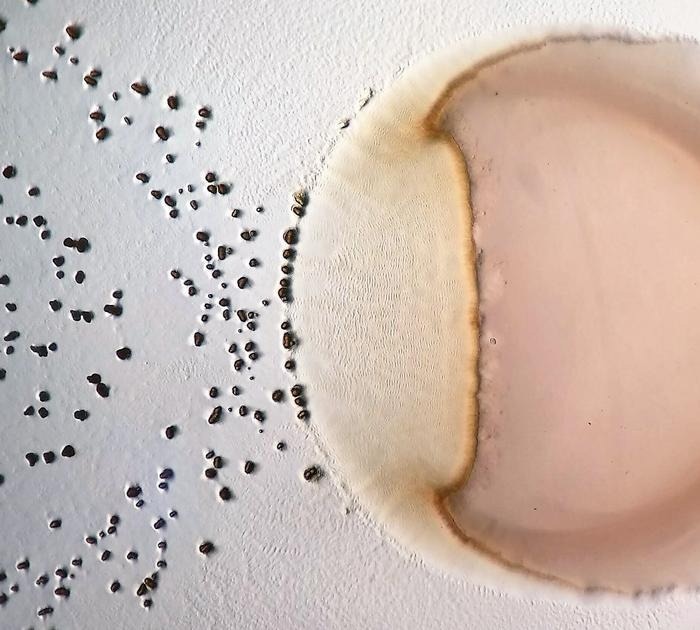

The predatory bacterium Myxococcus xanthus (left) slaughtering its prey (right). Black dots are predator aggregates called fruiting bodies and the rippling waves in the contact zone are characteristic of predatory interactions. Image Credit: Nicola Mayrhofer.

The predatory bacterium Myxococcus xanthus (left) slaughtering its prey (right). Black dots are predator aggregates called fruiting bodies and the rippling waves in the contact zone are characteristic of predatory interactions. Image Credit: Nicola Mayrhofer.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the ecological setting might affect predator-prey dynamics. For example, the degree of resemblance or contrast between a prey species' coloration and backdrop color might affect how quickly predators identify it.

Furthermore, predator-prey interactions can occasionally reverse, as in the case of two mutually feeding crab species, where a shift in the salinity of the surrounding environment reverses the dominant species. There are not many additional instances of this flipping occurring in reaction to ecological shifts that are not biological, though.

Certain bacteria feed on other bacteria, and the ecological setting can affect how effective a predator is. Building on this understanding, Vasse and associates carried out a number of lab tests to investigate the potential effects of temperature on the predator-prey dynamic involving the bacterial species Pseudomonas fluorescens and Myxococcus xanthus.

They discovered that M. xanthus behaved as the predator and killed many P. fluorescens when the latter was cultured in a plate at 32 ºC. The predator-prey dynamic changed, nevertheless, when P. fluorescens was cultivated at 22 ºC. P. fluorescens killed M. xanthus and used its nutrients to sustain itself.

To learn more about the mechanism by which growth at colder temperatures would have flipped the roles of predator and prey, the researchers ran additional tests. They focused on a non-protein material that P. fluorescens releases that is fatal to M. xanthus and whose synthesis seems to be temperature-dependent.

According to the researchers, their results imply that a variety of microbe-microbe killing processes that are not usually linked to predation, the eating of a dead organism by its killer may really cause it. The study highlights the significance of taking historical context into account when evaluating current predator-prey relationships.

They also point out that the temperature at which P. fluorescens grew prior to encountering M. xanthus may decide which would be the predator and which would be the prey when the two species meet later.

The results of this study and future research may contribute to the understanding of natural ecology and useful applications, such as maximizing the use of some microorganisms to control others.

The authors added, “We find it fascinating that a relatively small change in one ecological factor can determine who kills and eats whom in microbial predation. We suspect that microbe-microbe killing results in predation far more often than has previously been appreciated.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Vasse M, et.al., (2024). Killer prey: Ecology reverses bacterial predation. PLoS Biology. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002454