Gaining an understanding of how various cell types cooperate to form tissues, organs, and organ systems is one of the main objectives of basic biology.

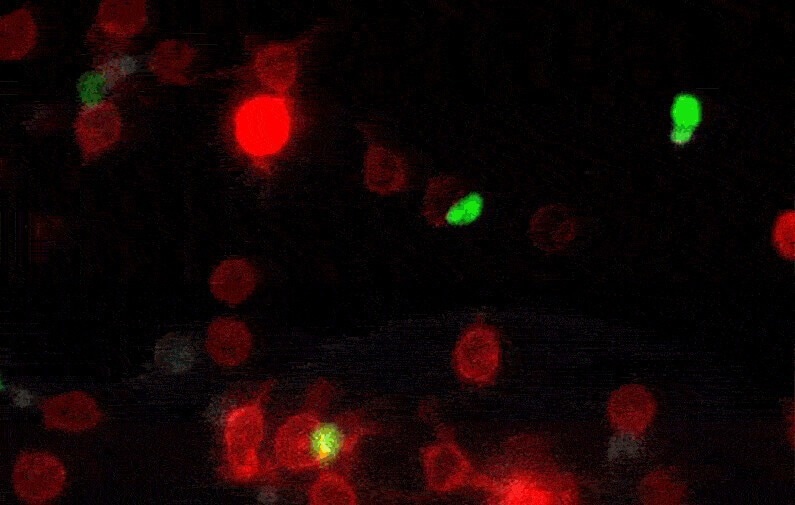

Immune cells interacting, tracked by the original LIPSTIC technology. Image Credit: The Rockefeller University

Immune cells interacting, tracked by the original LIPSTIC technology. Image Credit: The Rockefeller University

Recent attempts to record the many cell types found in every tissue in the human body are a good start, but they are only one piece of the jigsaw. How those cells communicate with each other is still a great mystery.

The elusive cellular interactome can now be tracked through a dynamic map, thanks to a tool called uLIPSTIC, which was recently described in a study published in Nature. Since 2018, the authors have been refining the technology, and the most recent version theoretically enables researchers to see any in vivo cell-to-cell interaction directly.

With uLIPSTIC we can ask how cells work together, how they communicate, and what messages they transfer. That’s where biology resides.”

Gabriel D. Victora, Laurie and Peter Grauer Associate Professor, The Rockefeller University

Kiss-and-run

Ever since the advent of single-cell mRNA sequencing, scientists have been frantically trying to piece together the details and explain how different cells come together to form tissue. There are already several approaches for cataloging cell-to-cell interactions, but they are all severely flawed.

Early efforts, which entailed direct observation under a microscope, failed to recover interacting cells for further research; subsequent attempts relied on improved imaging techniques that predicted how cells could interact based on their structure and proximity to others. True signal exchange and physical interactions between cell membranes were not captured by any method.

Enter LIPSTIC, an innovative strategy developed by the Victora lab that included identifying cellular structures that come into contact when two cells perform a momentary “kiss-and-run” before parting ways. The labels made sure that when a cell “kissed,” it would leave a lipstick-like mark, making it simple to identify and measure the physical interactions between cells.

The platform’s initial uses were limited. LIPSTIC was created by Victora and associated with the primary goal of documenting a very particular type of cell-to-cell interaction between T cells and B cells. However, other scientists started demanding that LIPSTIC be expanded to include additional cellular interactions.

Victoria added, “We could have tailored a LIPSTIC for every type of interaction. But why not try to make a universal version, instead?”

Mapping Every Interaction

When two cells come into contact in the original LIPSTIC model, a “donor” cell uses an enzyme derived from bacteria to attach a labeled peptide tag to the surface of the “acceptor” cell. This process is similar to putting lipstick on one cell and searching for a kiss print on another. To use that method, it was necessary to pinpoint the precise location of the “kiss,” identify the molecules the donor cell uses to communicate with recipient cells, and laboriously attach the tags to those molecules.

However, as time went on, the researchers found that submerging the cells in a large amount of the enzyme and its target would guarantee that every interaction a cell had with another would be recorded with the same level of efficiency.

Victora stated, “If you cram partner cells with enough enzyme and target, you can make any any cell pair capable of LISPTIC labeling without needing to know in advance what molecules these cells will use for their interaction.”

As a consequence, uLIPSTIC was created - a global platform unrestricted by knowledge of molecules, ligands, or receptors. Theoretically, researchers can now apply uLIPSTIC to any cell and observe actual cell-to-cell interactions without any preconceived assumptions about how the cell would behave in its surroundings.

To showcase the platform’s capabilities, the researchers demonstrated how uLIPSTIC could monitor how dendritic cells initiate the immune system’s defense against food allergies and tumors, going beyond LIPSTIC's limited repertoire of B cells and T cells.

The reception to uLIPSTIC has been great. We’re already getting a lot of inquiries from other labs about how they can adapt our system to their models.”

Sandra Nakandakari-Higa, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, The Rockefeller University

In an attempt to gain a deeper understanding of how cells combine to form tissue at the molecular level, the team eventually hopes to use uLIPSTIC to identify the receptor-ligand pairs essential to cellular interactions.

Eventually, the team hopes to use uLIPSTIC as a crucial tool in the endeavor to create complete atlases depicting how cells interact to make tissue—a cornerstone to the much-anticipated interactome.

Source:

Journal reference:

Nakandakari-Higa, S., et. al. (2024) Universal recording of immune cell interactions in vivo. Nature. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07134-4