A fungal disease called valley fever is on the rise in the western United States. It typically manifests as flu-like symptoms, but it can potentially have fatal or extremely serious side effects. Researchers from the University of California San Diego and University of California, Berkeley have discovered seasonal patterns in reported cases of Valley fever in California, which have sharply increased over the past 20 years.

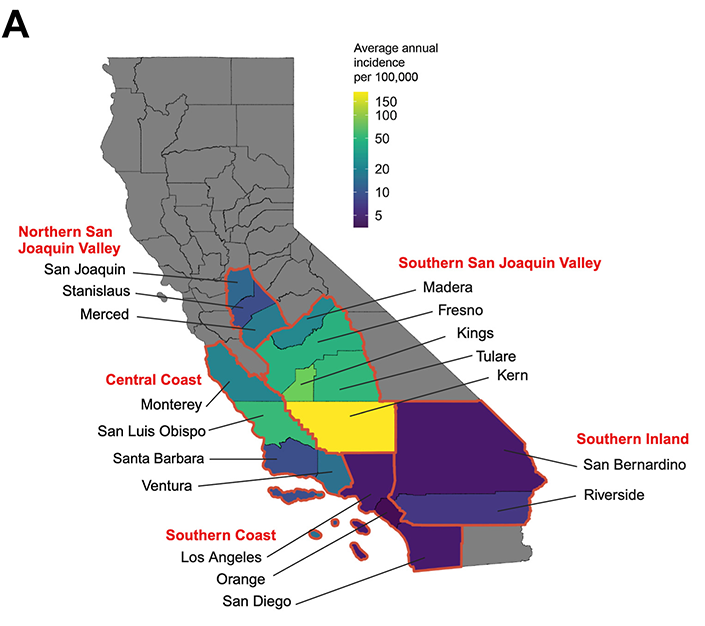

This map shows how the average incidence of Valley fever varies across different counties, with yellow and green representing higher incidence than blue and purple. Image Credit: UC San Diego Health Sciences

This map shows how the average incidence of Valley fever varies across different counties, with yellow and green representing higher incidence than blue and purple. Image Credit: UC San Diego Health Sciences

These patterns could aid individuals and public health officials in better preparing for future spikes in Valley fever cases. The results have significant ramifications for how infectious disease threats may increase as a result of climate change. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas published the findings.

The researchers worked closely with the California Department of Health (CDPH) to examine every instance of valley fever recorded in California between 2000 and 2021. By comparing these to seasonal climatic data, they found that the disease cycles seasonally throughout various California counties and is impacted by drought periods.

Although the majority of instances happened between September and November, the researchers discovered that different counties and years had different seasonal trends and timing.

Most seasonal infectious diseases show a peak in cases every year, so we were surprised to see that there were certain years during which few or no counties had a seasonal peak in Valley fever cases. This made us wonder what was driving these differences in seasonality between years, and based on the timing we observed, we hypothesized that drought might be playing a role.”

Alexandra Heaney, Ph.D., Assistant Professor and Study First Author, University of California, Berkeley

Although the peaks in the San Joaquin Valley started earlier, the researchers discovered that counties in the Central Coast and San Joaquin Valley regions had the most noticeable seasonal peaks on average.

“This is valuable information to time public health messaging aimed at educating the public about the symptoms of Valley fever and how to protect themselves,” added Heaney.

Spores from the soil-dwelling Coccidioides fungus are the source of valley fever. When the soil is disturbed by wind or human activity, pathogenic spores get aerosolized and people inhale them to contract Valley fever. Those who work outside or are regularly exposed to dust in the air are more likely to suffer from valley fever. The illness is not communicable.

Although valley fever has always been an issue in the American Southwest, the CDPH reports that cases have tripled between 2014 and 2018 and again between 2018 and 2022. However, valley fever is frequently misdiagnosed due to its relative rarity and similarity to other respiratory illnesses, such as COVID-19.

The fungus can spread to other bodily parts, including the skin, bones, and even the brain which can be fatal and seriously harm the respiratory system if left untreated.

Knowing when the Valley fever season starts and how intense it will be can help health care practitioners know when they should be on high alert for new cases. This is the first study to pin down exactly when disease risk is highest in all of California’s endemic counties, as well as places where the disease is newly emerging.”

Justin Remais, Ph.D., Professor and Study Corresponding Author, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley

The researchers noticed that seasonal surges in Valley fever cases are less severe during dry spells. Nevertheless, these heights are especially high when the rains come again. A possible explanation for this pattern is that heat-resistant Coccidioides spores are able to outlive their less resilient counterparts during droughts. The fungus can spread quickly when rains come back since there is less rivalry for moisture and nutrients.

According to a different theory, the connection between Valley fever and drought can stem from how the drought affects rodent hosts of the fungus Coccidioides. The fungus may be able to live and spread more readily in drought circumstances because rodent populations decrease during droughts and because deceased rodents are assumed to be a significant source of nutrients for the fungus.

This work is an important example of how infectious diseases are influenced by climate conditions. Even though droughts appear to decrease Valley fever cases in the short term, the net effect is an increase in cases over time, particularly as we experience more frequent and severe droughts due to climate change.”

Alexandra Heaney, Ph.D., Assistant Professor and Study First Author, University of California, Berkeley

When it is dry and dusty outside, people can help prevent Valley fever by staying indoors less and using dust-blocking face covers. The researchers stress the importance of conducting more extensive surveillance on the fungus known as Valley fever, which can be challenging to identify.

The group is currently broadening the scope of its research to encompass other American Valley fever hotspots.

Heaney said, “Arizona is much dustier than California and has very different climate dynamics, and about two thirds of cases in the United States occur in Arizona, so that is where we are looking next. Understanding where, when, and in what conditions Valley fever is most prevalent is critical for public health officials, physicians, and the public to take precautions during periods of increased risk.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Heaney, A. K., et al. (2024) Coccidioidomycosis seasonality in California: a longitudinal surveillance study of the climate determinants and spatiotemporal variability of seasonal dynamics, 2000–2021. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas. doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2024.100864.