The gut microbiome comprises the human gastrointestinal tract consisting of trillions of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea. The colon is known to hold the majority of microbiota with the highest level of host interaction, and with an increase in research in this area, there has been a compelling amount of evidence for the role gut microbiome has on mental health.

The gut microbiome. Image Credit: ART-ur/Shutterstock.com

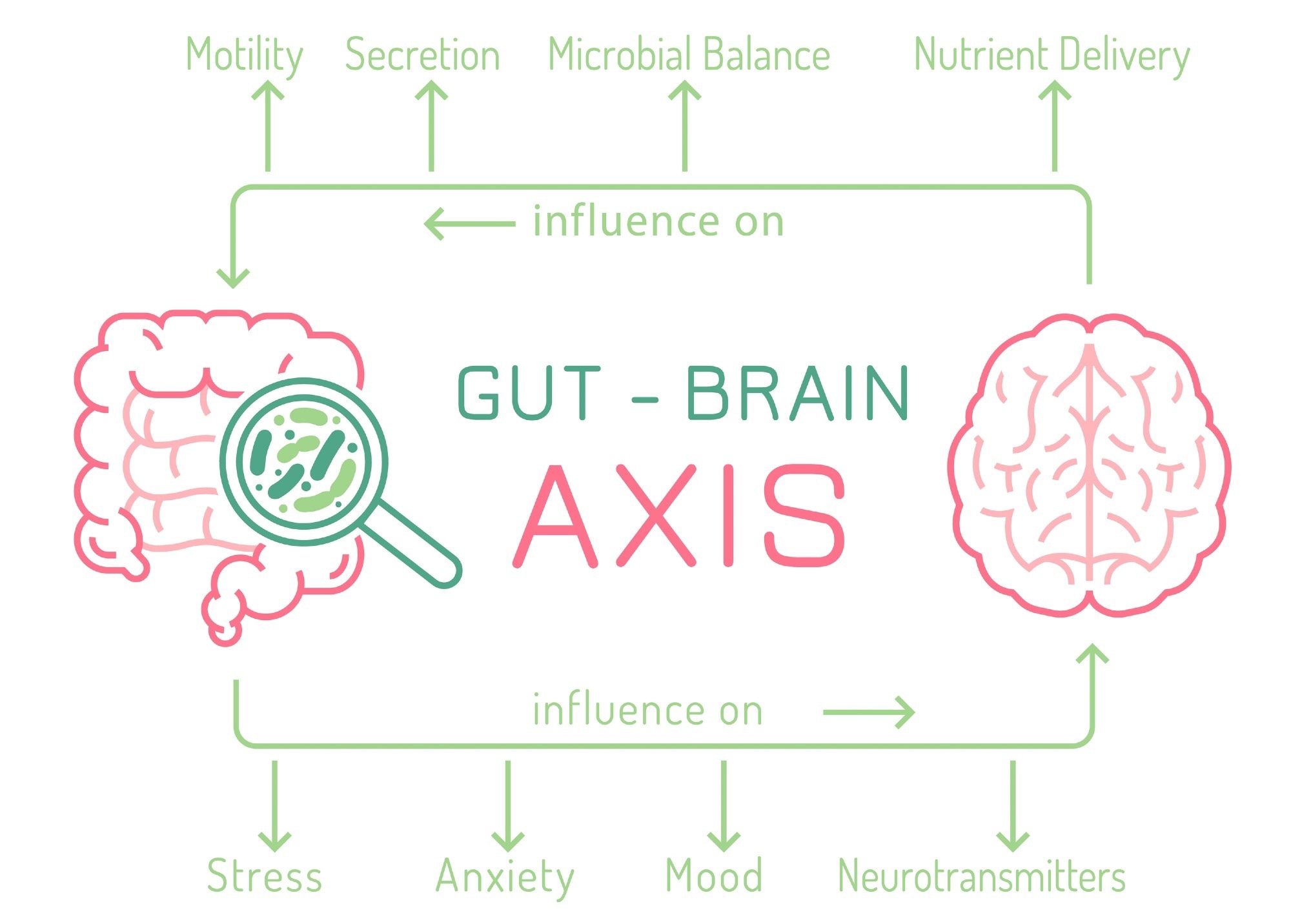

The gut microbiome is specific to individuals and can be influenced by many factors such as genetics, as well as environment, including growth, development, and location. The brain and gut have been noted to work bio-directionally, with one affecting the function of the other as well as influencing mental health issues, such as stress, depression, anxiety, and cognition.

Depression

Depression can be described as a mental illness, which includes a low emotional state, lack of confidence, as well as apathy, due to a mixture of genetics and the environment. This is significant as the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported major depressive disorder (MDD) as the highest contributor to the global disease burden, with approximately 350 million being affected by depression worldwide.

Research has found a connection between the brain and the gut microbiome with healthy microflora transmitting brain signals through pathways related to neurogenesis, transmission of neurons, activation of the microglia and behavioral control. This brain-related pathway has provided strong evidence of the role of the microbiome in mental health management.

Depression patients have also been found to have dysregulated brain function relating to neuroendocrine and neuroimmune pathways, which have been found to contribute to disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by abdominal pain and inconsistent bowel habits.

Patients with IBS have demonstrated a lower pain threshold to rectal distension, having an increased visceral sensation, as well as increased activity in the CNS pain matrix involving the thalamus, insula and anterior cingulate cortex. This can be correlated with patient disposition, with research findings including high comorbidity of having stress-related disorders comprising depression and anxiety.

Interestingly, the two-way communication system involving the brain and gut signaling can also indicate the role stress can have on gastrointestinal symptoms, with significant evidence being found in relating stress to the initiation, intense increase, and persistence of symptom flares found in the gut.

This microbiome-gut-brain axis has increased research interest into the dual relationship the brain and gut have with each other, with some thinkers even arguing the status of the gut as being ‘an organ of the mind’. With the microbiome possibly being responsible for mental health problems, this may change the way in which mental health is understood, with a higher level of overlap between mental health, psychiatry, and biomedical sciences.

The gut-brain axis. Image Credit: Double Brain/Shutterstock.com

Mediating Stress

Stress hormones such as corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) are released in response to stress in order to mediate these levels within the body through neurons of the hypothalamus. CRF can be produced in response to perceived stressors by the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, causing increased cortisol secretion in IBS patients.

However, sensitivity to stress may be altered in patients with IBS, evidenced by the high comorbidity of stress-related disorders such as depression and anxiety. This has led to research into inhibiting CRF receptors in order to improve bowel function in IBS patients; however, while preclinical trials have illustrated how CRF-1 antagonists reduced colonic motility as well as diarrhea in stressed rats, a double-blind study published in the journal, Nature, did not have optimistic results.

While mood disorders including anxiety, depression and even autism have been established to have associations with gastrointestinal functionality, as well as the correlation of a healthy gut with normal CNS function, there may be more research required to fully comprehend this relationship. This comprehension may aid in achieving effective management of both types of disorders.

Future Outlook

The gut microbiome holds a very significant role in mental health, with the microbiome-gut-brain axis having a dual relationship, both having an impact on the other. This can be significant for both mental health as well as gastrointestinal disorders as it may provide a higher level of biological targets for drug manufacturers. In turn, this would optimize the approach of targeting both mental health and gastrointestinal disorders, which may be revolutionary for a large population of sufferers.

Disorders such as IBS are complicated, with a lack of current understanding within research; however, improving the comprehension of gastrointestinal disorders and maintaining a healthy gut microbiome may potentially alleviate mental health. Additionally, understanding the connection between mental health disorders and gastrointestinal disorders may aid in reducing stress and stress-related comorbidities.

Sources

- Allison, S. CRF-1 antagonists fail to improve bowel function in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6, 441 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2009.113

- Appleton J. The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17(4):28-32.

- Clapp M, Aurora N, Herrera L, Bhatia M, Wilen E, Wakefield S. Gut Microbiota’s Effect on Mental Health: The Gut-Brain Axis. Clin Pract. 2017;7(4):987. doi:10.4081/cp.2017.987

- Limbana T, Khan F, Eskander N. Gut Microbiome and Depression: How Microbes Affect the Way We Think. Cureus. 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.9966

- Lucas G. Gut thinking: the gut microbiome and mental health beyond the head. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2018;29(2):1548250. doi:10.1080/16512235.2018.1548250

- O'Malley D. Neuroimmune Cross Talk in the Gut. Neuroendocrine and neuroimmune pathways contribute to the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2016;311(5):G934-G941. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00272.2016

Further Reading

Last Updated: Oct 14, 2022