Cellular immunotherapy, or adoptive cell therapy, is an innovative treatment approach that uses the cells of our immune system to fight cancer. The main goal of anti-cancer immunotherapy is to harness our immune system to recognize and destroy tumor cells. Using adoptive cell therapy, tumor-specific cytotoxic T-cells are administered to cancer patients to recognize, target, and destroy tumor cells.

Image Credit: Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics/Shutterstock.com

Immunity, cancer, and adoptive cell therapy

Cancer immunotherapies use immune system components to circumvent and reverse the cancer evasion strategies employed by tumors and boost immunity against cancerous cells. There are two main types of cancer immunotherapies: active and passive immunotherapies based on the stimulation of the host immunity. Active immunotherapy boosts the host defenses and can be classified as specific and non-specific.

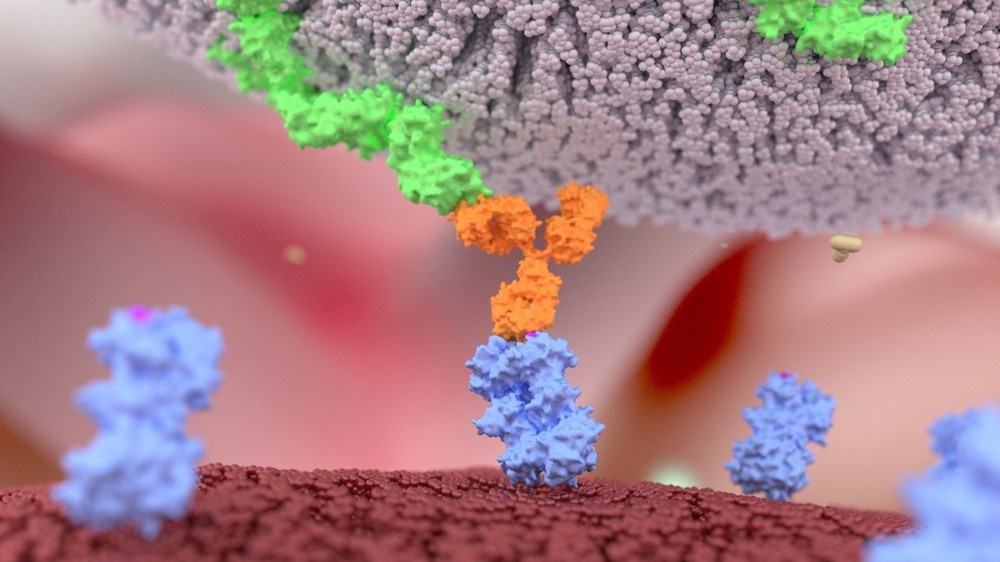

Prophylactic or therapeutic vaccines, specific immunotherapies, can induce the host immune system against a specific antigen, whereas non-specific immunotherapy is based on checkpoint inhibitors, cytokines, and immune adjuvants, increasing the host immunity. On the other hand, passive immunotherapy does not boost the host immunity and involves adoptive cell transfer, as well as the passive transfer of small molecules or tumor-targeting monoclonal antibodies.

Cellular immunotherapy is based on the administration of living cells to patients; this immunotherapy form could be active like dendritic cell vaccines, in that the cells can stimulate anti-tumor responses in patients, or the therapy could be passive, where the cells have intrinsic anti-tumor capabilities; this is known as "adoptive cell transfer" and involves the utilizing of allogeneic or autologous lymphocytes that can, or cannot, be modified.

Adoptive cell therapies involve the transfer of cells which have been primed in response to tumor antigens into the host; in most cases, these cells are autologous. However, there are current researches to use allogeneic cells as off-the-shelf products. In contrast to adoptive T-cell therapy, vaccines can prime the adaptive immunity to stimulate a response against tumors. In adoptive T-cell therapy, the effector cells are pre-primed via "in vivo" or "ex vivo" exposure to antigens.

One of the human immune system's main features is recognizing and eliminating infected or cancerous cells. Some cellular immunotherapies directly isolated immune cells and increased their numbers, while others genetically engineered immune cells to improve their cancer-targeting features using gene therapy.

Due to the specific ability of killer T-cells to bind to antigens on the surface of cancer cells, they play an important role in targeting cancerous cells. Adoptive cell therapy takes advantage of this unique ability and can be used in several ways, such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL), engineered T-cell receptor (TCR), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells.

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy

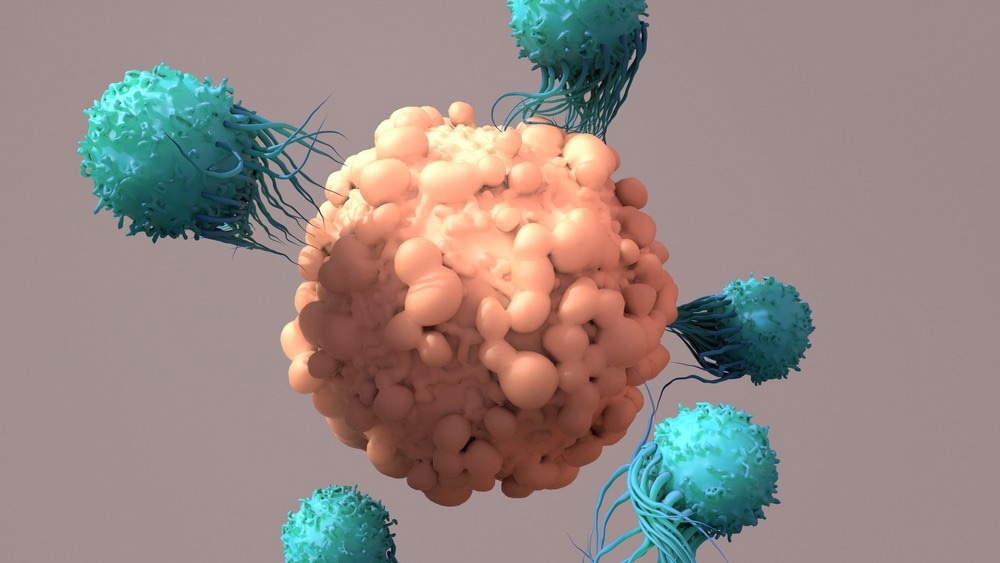

The T-cells in cancer patients can target their cancerous cells. The killer T-cells play a very important role in precisely recognizing and destroying cancerous cells. However, there is no guarantee that T-cells alone can eliminate tumors because of two factors: number and activation. For example, T-cells should exist in sufficient numbers and to be active. If T-cells are not activated, they cannot effectively destroy cancerous cells.

Adoptive cell therapy uses tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy to address these previous limitations. Naturally occurring T-cells, which have already infiltrated patient tumors, will be harvested. Then, they will be activated and expanded. Many of these activated T-cells are again infused into patients, where they can target and destroy cancerous cells.

Image Credit: Design_Cells/Shutterstock.com

Engineered T-Cell Receptor (TCR) Therapy

The T-cells of some cancer patients may not have been activated and/or expanded to sufficient numbers to eliminate cancerous cells effectively. In this case, engineered T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy could be helpful. In TCR therapy, T-cells will be taken from cancer patients, but instead of only activating and expanding the available anti-tumor T-cells, these T-cells will also be equipped/supported with new T-cell receptors that allow them to target particular cancer antigens, which could be considered as a personalized treatment approach for cancer.

CAR T-Cell Therapy

The previous TCR and TIL therapies could only seek out and eliminate/remove cancerous cells, which have their antigens presented by the major histocompatibility complex. However, this drawback could be overcome by equipping T-cells of the patients with synthetic receptors known as chimeric antigen receptors (CAR), allowing them to bind to cancerous cells even if their antigens aren't presented on the surface via a major histocompatibility complex, rendering more cancerous cells vulnerable to CAR T-cell attacks.

But, CAR T-cell recognizes antigens that themselves are naturally expressed on the cell surfaces, making the range of potential antigens smaller than with TCR.

Sources:

- Perica, Karlo, et al. "Adoptive T cell immunotherapy for cancer." Rambam Maimonides medical journal 6.1 (2015).

- Berraondo, Pedro, et al. "Cellular immunotherapies for cancer." Oncoimmunology 6.5 (2017): e1306619.

- Vigneron, Nathalie, and Benoît J. Van den Eynde. "Insights into the processing of MHC class I ligands gained from the study of human tumor epitopes." Cellular and molecular life sciences 68.9 (2011): 1503-1520.

- Schlom, Jeffrey, Philip M. Arlen, and James L. Gulley. "Cancer vaccines: moving beyond current paradigms." Clinical Cancer Research 13.13 (2007): 3776-3782.

- Hogquist, Kristin A., Troy A. Baldwin, and Stephen C. Jameson. "Central tolerance: learning self-control in the thymus." Nature Reviews Immunology 5.10 (2005): 772-782.

- Pardoll, Drew M. "The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy." Nature Reviews Cancer 12.4 (2012): 252-264.

- Gorelik, Leonid, and Richard A. Flavell. "Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-β signaling in T cells." Nature medicine 7.10 (2001): 1118-1122.

Further Reading