Disease tolerance and disease resistance are the two major defense strategies humans have evolved to protect themselves against pathogenic infection.

Disease. Image Credit: ffikretow/Shutterstock.com

Disease resistance focuses on protecting the host by killing invading pathogens, and for a long time, it was believed to be the only strategy we had to prevent infection. Disease tolerance protects against infection while refraining from exerting a negative effect on the pathogen load, in some cases, it may even have a positive impact.

This alternative strategy was first observed in plants and was not observed in humans until 2006. As we will detail below, the strategy relies on control mechanisms of tissue damage, which in turn rely on stress and damage responses. These responses are regulated by the innate and adaptive immune system and are responsible for establishing disease tolerance to infection. Pharmacological targeting of these mechanisms involved in tissue damage control induces disease tolerance, demonstrating the vital importance of this pathway.

Discovering disease tolerance in humans

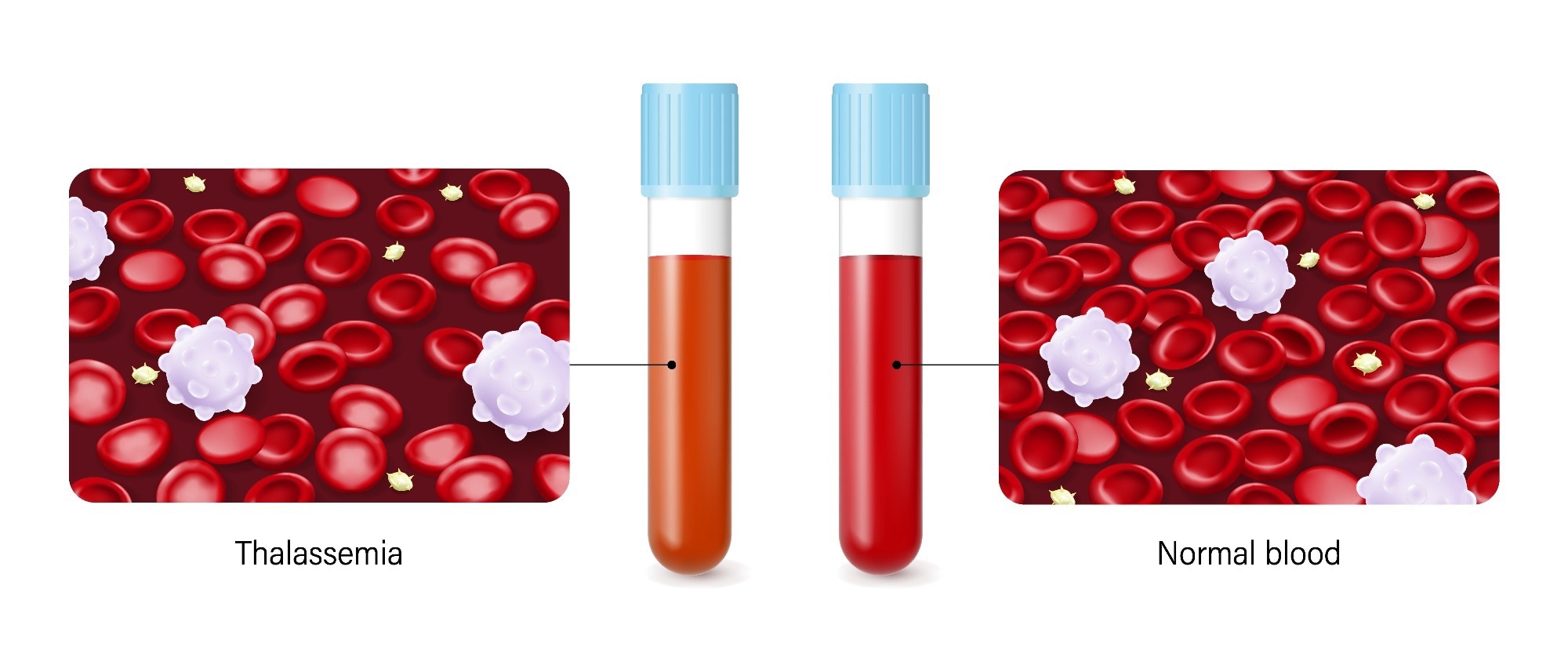

Until 2006, scientists had believed that disease tolerance was unique to plants. A study looking into the impact of alpha thalassemia, a blood disorder that reduces hemoglobin production, on the incidence of malaria in children in Kenya found that the disease induces a level of protection against the severe iron deficiency that is common in malaria.

Following this, in 2007, disease ecologist Andrew Read and his colleague Lars Råberg at the University of Edinburgh discovered that genetic variations were present in some types of mice that enhanced their tolerance to Plasmodium chabaudi, a malaria-causing parasite. While the mice did not have a reduction in the number of parasites, demonstrating that the disease resistance mechanism was not to blame for this outcome, they were more tolerant to infection than the other mice.

Perhaps the most important paper that first cemented the idea of disease tolerance in animals was that of Ayres and Schneider who, in 2008, published their findings that genetic variations had a significant impact on the longevity of flies while no differences in pathogenic load were observable between those who lived long and those who perished. It was at this point that scientists realized that disease tolerance was not unique to plants as it was also observed in animals.

An overview of the disease tolerance defense strategy

The human immune system evolved to protect the body from the detrimental, and sometimes fatal, effects that invading pathogens have on host homeostasis. The innate and adaptive branches of the immune system work in harmony to initiate detect and target pathogens for containment, killing or expulsion.

When a person is considered to have developed resistance to a disease, it means that their immune system is enabled to reduce the load of the pathogen that causes the disease to preserve homeostasis and stave off the negative biological impact of the disease-causing pathogen.

Disease tolerance works alongside this immune-driven resistance by limiting the extent of dysfunction caused to parenchymal tissues during infection without damaging the pathogens. Relying on tissue damage control mechanisms, disease tolerance works by preventing the detrimental effects of pathogens on the body and on the immune-driven response.

A study looking into the impact of alpha thalassemia, a blood disorder that reduces hemoglobin production, on the incidence of malaria in children in Kenya found that the disease induces a level of protection against the severe iron deficiency that is common in malaria. Image Credit: Dee-sign/Shutterstock.com

A study looking into the impact of alpha thalassemia, a blood disorder that reduces hemoglobin production, on the incidence of malaria in children in Kenya found that the disease induces a level of protection against the severe iron deficiency that is common in malaria. Image Credit: Dee-sign/Shutterstock.com

Mechanisms of disease tolerance

When a pathogen invades our body, it is the immune system’s job to detect, target, and remove this pathogen (via killing it or expelling it) to prevent us from falling ill from the impact of the pathogen on the body’s homeostasis. Vaccines prepare the adaptive immune system to fight off certain kinds of pathogens, as does prior exposure to a pathogen, while the innate system that you were born with protects the body indiscriminately from all invading pathogens.

Antibiotics and antiviral drugs also help the body in its fight against pathogens. However, when we feel sick from a bacterial or viral infection, it is often due to the body’s own response against infectious pathogens. Inflammation and fever induced by the immune response make us feel unwell and the medicines we take (other than antibiotics and antiviral medicine) often target the effects of the immune system, not the pathogen.

Recently, scientists have realized that the body promotes health in the same way that we treat infections with medicine to fight symptoms of the immune response. Disease tolerance protects the body from the damage that would occur to it as a result of the infection. Rather than targeting the pathogen causing the illness, disease tolerance targets the body. In that way, pathogens can exist within our bodies without making us sick.

Tapping into disease tolerance to treat infections

Researchers are currently exploring ways to exploit disease tolerance mechanisms in order to develop new therapeutic approaches to treating infectious diseases. However, the mechanisms of disease tolerance are often unique to the pathogen causing the disease, and, therefore, much more research is needed to understand these unique mechanisms before disease tolerance can successfully be leveraged into therapeutic approaches.

Sources

- Martins, R. et al., 2019. Disease tolerance as an inherent component of immunity. Annual Review of Immunology, 37(1), pp.405–437. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30673535/

- McCarville, J.L. & Ayres, J.S., 2018. Disease tolerance: Concept and Mechanisms. Current Opinion in Immunology, 50, pp.88–93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5884632/

- Soares, M.P., Teixeira, L. & Moita, L.F., 2017. Disease tolerance and immunity in host protection against infection. Nature Reviews Immunology, 17(2), pp.83–96. https://www.nature.com/articles/nri.2016.136#citeas

Further Reading

Last Updated: Oct 14, 2022