When a corpse is discovered, one of the foremost things a forensic pathologist would do is to predict the time of death.

There are many ways to perform this process, such as observing the insects’ activity and measuring the body temperature; however, these techniques do not invariably work for dead bodies found in water.

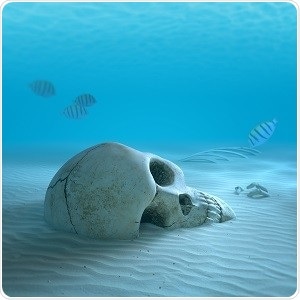

Examining certain proteins in bones could help determine how long they’ve been underwater, as in this illustration. Image Credit: Johan Swanepoel/Shutterstock.com.

Recently, scientists have reported a mouse study in ACS’ Journal of Proteome Research, demonstrating that specific proteins in bones could be utilized for this determination.

A precise estimate of the actual time of death can assist investigators to gain more understanding of what exactly happened to the individual and can help them recognize potential murder suspects if a crime was involved.

But it can be very difficult to find out the post-mortem submerged interval (PMSI), or the duration of time a corpse had remained underwater.

One method is to analyze the decomposition stage of many parts of the body, but factors like temperature, depth, tides, water salinity, scavengers, and the presence of bacteria can make PMSI estimation rather complicated.

But compared to soft tissues, bones are much stronger and lie deep inside the body, and hence the proteins present inside the bones could be protected from some of these impacts.

Therefore, Noemi Procopio and collaborators speculated whether tracking the levels of specific proteins in bones could expose the amount of time a mouse’s dead body remained underwater, and also whether various types of water mattered.

To find out more about this, the scientists placed the carcasses of fresh mice in bottles of chlorinated water, pond water, saltwater, and tap water. Following a PMSI of one or three weeks, the researchers collected the lower leg bones, or tibia, from the dead animals, obtained the proteins, and examined them by mass spectrometry.

The scientists noted that the duration of time since submersion had a higher impact on protein levels when compared to the different types of water. Specifically, a protein known as fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A reduced in the bone as PMSI increased.

Pond water contains a protein known as fetuin-A. This protein is more likely to go through chemical modification, referred to as deamidation, than in other kinds of water, which could help expose if a corpse was once immersed in pond water and later moved.

These and other promising biomarkers detected in the research could be handy for PMSI estimation in different aquatic settings, concluded the scientists.