According to a study published in the Scientific Reports journal, the frequency of genetic variants linked to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has reduced progressively in the evolutionary human lineage from the Palaeolithic to the present day.

According to the study, some features like hyperactivity or impulsiveness could have been favorably selected for survival in ancestral environments dominated by a nomad lifestyle. Image Credit: Paula Esteller (CNAG-CRG/IBE, CSIC-UPF).

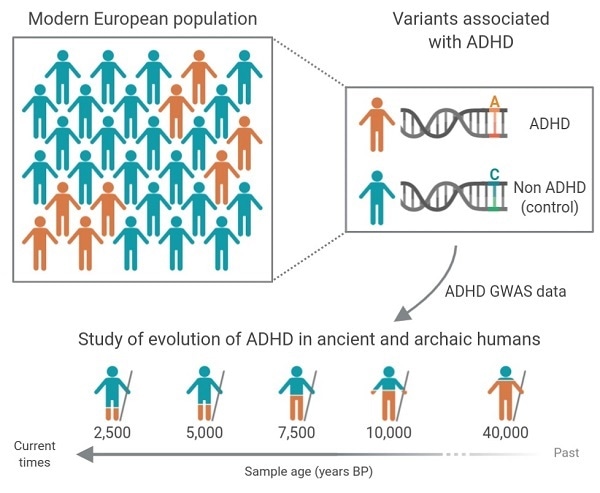

The unique genomic analysis compares many ADHD-related genetic variants explained in current European populations to evaluate its evolution in samples of Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and in samples of the human species (Homo sapiens)—both ancient and modern.

As per the conclusions, the low tendency seen in European populations could not be elucidated for the introgression of Neanderthal genomic segments in the human genome or the genetic mix with African populations.

The latest genomic study was headed by Professor Bru Cormand from the Faculty of Biology and the Institute of Biomedicine of the University of Barcelona (IBUB), the Research Institute Sant Joan de Déu (IRSJD) and the Rare Diseases Networking Biomedical Research Centre (CIBERER), and the researcher Oscar Lao, from the Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico (CNAG), which is part of the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG).

The research counts on the participation of research teams from the Aarhus University (Denmark) as well as the Upstate Medical University of New York (United States).

The first author is the CNAG-CRG researcher Paula Esteller, a present doctoral student at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE, CSIC-UPF).

ADHD: An adaptive value in the evolutionary lineage of humans?

ADHD is a modification of the neurodevelopment which can have a major impact on the life of the affected individuals. Common in today’s population, ADHD is characterized by attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness.

It has a prevalence of 5% in adolescents and children and can last up to adulthood.

From an evolutionary point of view, one would believe that anything harmful would vanish among the population.

To clarify this phenomenon, many natural hypotheses have been presented, mainly focused on the context of the transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, like the known Mismatch Theory.

According to this theory, cultural and technological changes that occurred over the last thousands of years would have allowed us to modify our environment in order to adopt it to our physiological needs in the short term. However, in the long term, these changes would have promoted an imbalance regarding the environment in which our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved.”

Study Authors, University of Barcelona

Hence, a number of traits like impulsiveness and hyperactivity, which are characteristic in ADHD-affected people, could have been selectively preferred in hereditary settings governed by a nomad lifestyle.

But the same kind of features would have turned out to be non-adaptive in other settings related to more recent times (mostly sedentary).

Why is it one of the most common disorders in children and adolescents?

Based on the research performed on 35,000 controls and 20,000 ADHD-affected people, the new study demonstrated that the genetic variants and alleles related to the ADHD disorder are likely to be present in genes.

Such genes are intolerant to mutations that result in loss of function, underscoring the existence of selective pressure on this phenotype.

According to the authors, the current high prevalence of ADHD could be an outcome of a favorable selection that occurred in the past. While being an unfavorable phenotype in the new environmental context, the prevalence would still continue to remain high because not much time has passed for it to disappear.

But due to the lack of available genomic data for ADHD, none of the theories has been empirically contrasted, to date.

Therefore, the analysis we conducted guarantee the presence of selective pressures that would have been acting for many years against the ADHD-associated variants. These results are compatible with the mismatch theory but they suggest negative selective pressures to have started before the transition between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic, about 10,000 years ago.”

Study Authors, University of Barcelona

Source:

Journal reference:

Esteller-Cucala, P., et al. (2020) Genomic analysis of the natural history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using Neanderthal and ancient Homo sapiens samples. Scientific Reports. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65322-4.