When pathogenic bacteria infect humans, the body’s immune system attempts to remove these invaders. One method to do this is to trigger an inflammatory response, which is a series of events comprising the activation of immune cells, the expression of protective proteins, and a process of controlled apoptosis when infected cells cannot be rescued.

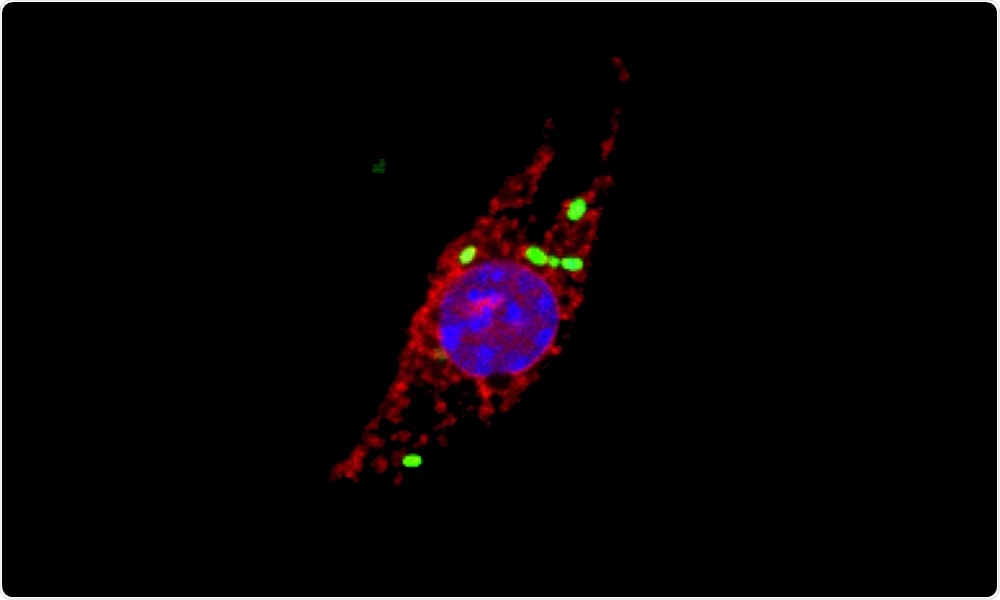

When immune cells called macrophages get infected by the intracellular pathogen Salmonella enterica (shown in green), cellular proteins of the cathepsin family (red, indicating cathepsin activity) localize to the nucleus (blue). Image Credit: Joel Selkrig/European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

Researchers, including members of European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL)’s Typas group, members of the team of EMBL alumnus Jeroen Krijgsveld at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) based in Heidelberg, and other colleagues, have performed an investigation on how the immune cells, known as macrophages, react to infection caused by the intracellular pathogen Salmonella enterica.

The researchers used a technique that was newly developed in their laboratories to detect, enrich, and measure all recently produced proteins from macrophages infected by Salmonella. The researchers marked the newly created proteins with a certain chemical label and detected them through a technique known as mass spectrometry. This technique enabled them to examine the whole set of cellular proteins.

Most significantly, the researchers quantified the protein levels in macrophages at different stages of infection and across different compartments of cells. The team’s study, published in the Nature Microbiology journal, demonstrates that tracking the dynamic changes both in the production and targeting of proteins can provide a better understanding of the mechanisms through which the cells react to microbes.

One of the unexpected study outcomes was that a popular class of proteins, known as cathepsins, migrates to a new site when the cells get infected by Salmonella. Cathepsins are proteases, that is, proteins that disintegrate other proteins.

Generally, cathepsins remain inside small subcellular structures called lysosomes and have earlier been implicated to promote cellular death, even though the mechanism or any association between the bacterial infection and process was not known.

The researchers have currently found that Salmonella causes the build-up of newly synthesized cathepsins in the nuclei of infected cells. Within the nucleus, the protein degrading activity of cathepsins is subsequently needed to trigger an inflammatory form of programmed cell death.

The latest research depicts the advantages of methodically following the dynamics of proteins during infection, which can reveal novel mechanisms and pathways used by the host to protect itself from the microbes.

Source:

Journal reference:

Selkrig, J., et al. (2020) Spatiotemporal proteomics uncovers cathepsin-dependent macrophage cell death during Salmonella infection. Nature Microbiology. doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0736-7.