Cheating mitochondria can exploit cellular mechanisms for dealing with the scarcity of food in a simple worm to persist, although this can decrease the wellbeing of the worm.

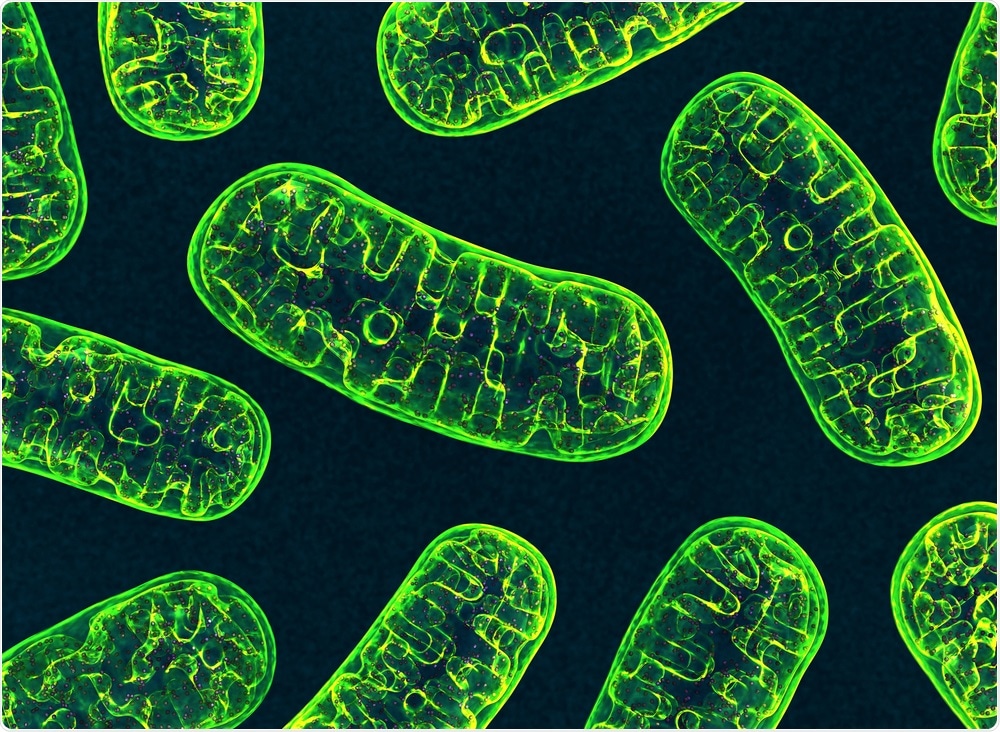

Image Credit: 3d_man/Shutterstock.com

Recently published in the eLife journal, these latest findings can provide a better understanding of the evolution of cooperative and cheating behaviors within different kinds of organisms.

Mitochondria are essentially the energy-producing units inside cells that probably evolved from microorganisms. These units have their own DNA, absorb resources from cells, and, in exchange, provide energy to the cell.

However, a few so-called “cheater mitochondria” have dangerous DNA modifications that may decrease their energy output and damages the organism. Scientists are still unclear as to why these cheater mitochondria persist in spite of causing harm to the larger organism.

Cooperation and cheating are widespread evolutionary strategies. While cheating confers an advantage to individual entities within a group, competition between groups favours cooperation.”

Bryan Gitschlag, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

Gitschlag and his collaborators examined the roundworm Caenorhabiditis elegans to observe how competing evolutionary pressures inside its cells and in its surrounding might allow the cheater mitochondria to persist.

The team quantified the levels of typical and cheater mitochondria in the cells of the worm. They identified that inside the cells, a protein known as DAF-16—which helps cells to endure stress—is required for the cheater mitochondria to grow in numbers.

When the worms encounter food scarcity, cheater mitochondria become more dangerous to their hosts, but only in those worms that lack the DAF-16 protein.

This shows that food scarcity can strengthen evolutionary selection against worms carrying cheater mitochondria, but DAF-16 protects them from it.”

Bryan Gitschlag, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

These results indicate that competing selection pressures inside an organism as well as its surrounding may offer a better understanding of why cooperation and selfishness usually exist side-by-side among populations.

The ability to cope with scarcity can promote group-level tolerance to cheating, inadvertently prolonging cheater persistence.”

Maulik Patel, Study Senior Author and Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

“As selfish mitochondrial genomes are implicated in numerous disorders, and cheating is a widespread evolutionary strategy, it will be interesting to apply our methods to study a broader collection of cheating variants and host species. This could allow us to better understand the development of mitochondrial disorders or the evolutionary principles underlying cooperation and cheating,” Patel concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Gitschlag, B. L., et al. (2020) Nutrient status shapes selfish mitochondrial genome dynamics across different levels of selection. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.56686.