According to recent findings, the genome of single-celled plankton, called dinoflagellates, is arranged in an extremely unusual and strange manner. The study results set the foundations for further research into these vital aquatic species and significantly broaden the understanding of what a eukaryotic genome can look like.

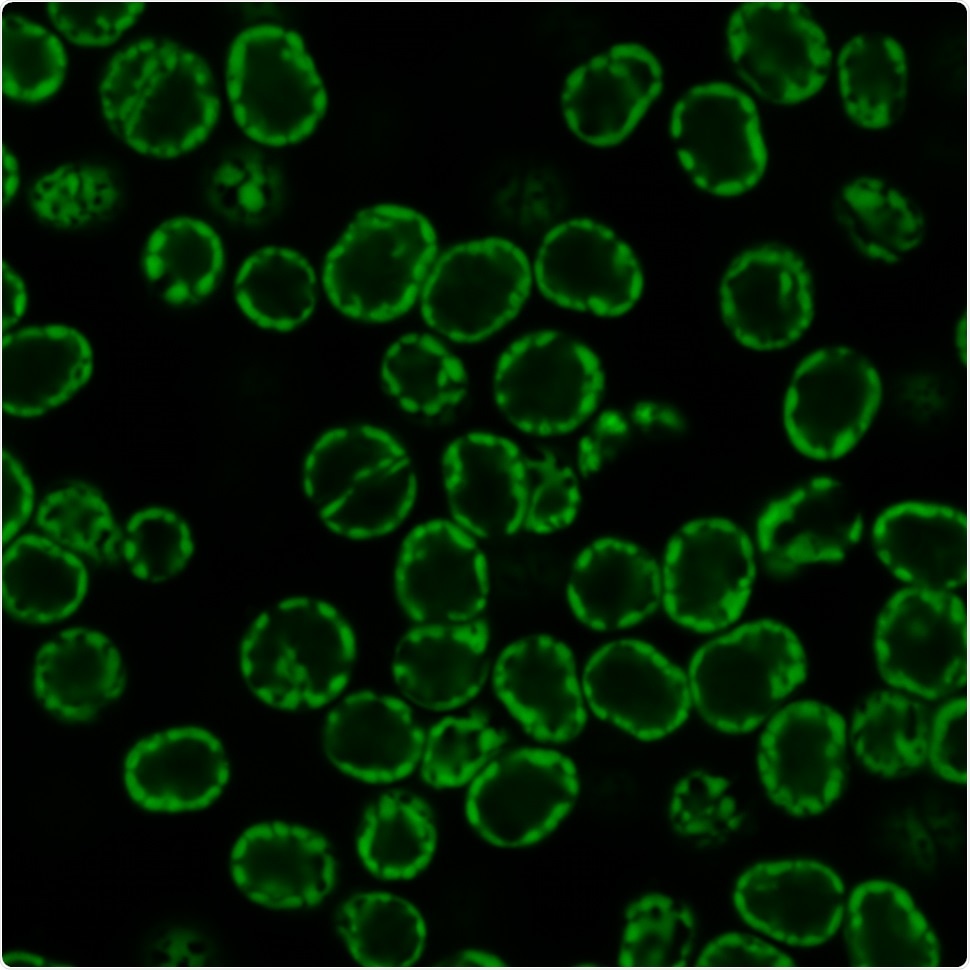

The international research team discovered that the genome of dinoflagellates is organized in a unique way compared to other eukaryotic genomes. Image Credit: © 2021 KAUST.

The genomic organization of the coral-symbiont dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum has been studied by a group of researchers from KAUST, the United States, and Germany. The genome of S. microadriaticum had already been sequenced and organized into scaffold fragments, but it lacked chromosome-level assembly.

The researchers used a method called Hi-C to identify associations in the chromatin of a dinoflagellate, which is a mixture of protein and DNA that forms a chromosome. Through the observation of these associations, they were able to determine how the scaffolds were linked together to form chromosomes, providing insights into the genome’s structural and spatial organization.

The fact that the genes in the genome appeared to be arranged in alternating unidirectional blocks was an eye-opening discovery.

That’s really, really different to what you see in other organisms.”

Octavio Salazar, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, Manuel Aranda’s Group, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

Gene orientation on a chromosome is normally random. However, in this case, genes were consistently oriented in a single direction and then the other, with the boundaries between blocks easily visible in the chromatin interaction data.

Nature can work in a completely different way than we thought.”

Octavio Salazar, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, Manuel Aranda’s Group, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

This organization is mirrored in the genome’s three-dimensional structure, which the researchers deduced as consisting of rod-shaped chromosomes that fold into structural domains at the boundaries where gene inhibits convergence.

Much more surprising was the fact that this arrangement seems to be transcriptionally dependent. The structural domains vanished when the researchers treated cells with a chemical that inhibits gene transcription.

This peculiar link is consistent with another strange fact regarding dinoflagellates: their genome exhibits very few transcription factors and they do not seem to react to environmental changes by modifying gene expression.

They can use gene dosage to regulate expression and adapt to the environment by gaining or losing chromosomes or possibly by epigenetic structural changes. All of these questions will be investigated by the researchers.

Another unanswered mystery is the cause of this unusual genome structure. Dinoflagellates contain relatively few histones, the proteins used by other eukaryotes to structure their DNA, and rather rely on viral proteins that were long ago embedded into their genome. The remarkable genome structure and genetic regulation may be a result of how these viral proteins function, although this is yet to be proven.

The genome of a dinoflagellate defies expectations and dogmas developed by observing other eukaryotes.

It shows that nature can work in a completely different way than we thought. There are so many possibilities for what could have happened as life evolved.”

Octavio Salazar, Study Lead Author and PhD Student, Manuel Aranda’s Group, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

Source:

Journal reference:

Nand, A., et al. (2021) Genetic and spatial organization of the unusual chromosomes of the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum. Nature Genetics. doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00841-y.