Reviewed by Dan Hutchins, M.PhilAug 23 2021

Researchers who earlier created a recipe for turning skin cells into primitive muscle-like cells that can be sustained indefinitely in the laboratory without losing the ability to become mature muscle have now unraveled how this recipe acts and the molecular changes it triggers inside cells.

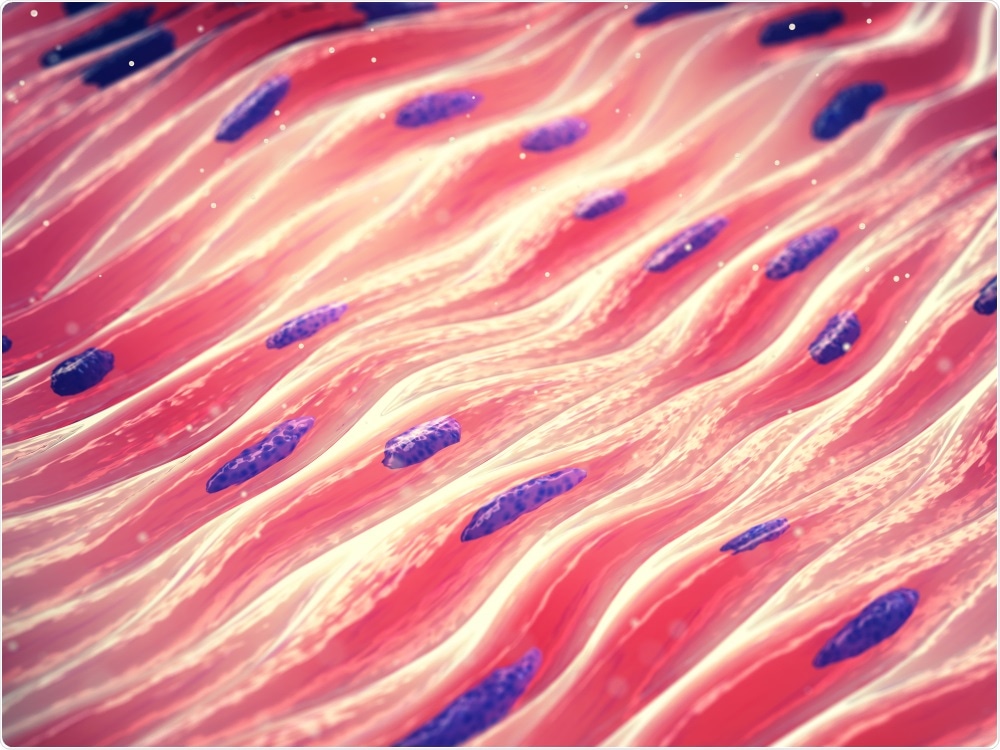

Muscle Cells. Image Credit: nobeastsofierce/Shutterstock.com

The study headed by researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and published in the Genes & Development journal could enable clinicians to create patient-matched muscle cells to help treat muscle injuries, aging-related muscle degeneration, or conditions like muscular dystrophy.

It is widely known that expression of a muscle regulatory gene called MyoD is adequate to directly convert skin cells into mature muscle cells, but mature muscle cells do not divide and self-renew, and hence cannot be propagated for clinical causes.

To address this shortcoming, we developed a system several years ago to convert skin cells into self-renewing muscle stem-like cells we coined induced myogenic progenitor cells or iMPCs. Our system uses MyoD in combination with three chemicals we previously identified as facilitators of cell plasticity in other contexts.”

Konrad Hochedlinger PhD, Study Senior Author and Principal Investigator, Center for Regenerative Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital

Hochedlinger is also a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

In the current research, Hochedlinger and his co-workers discovered the details on how this combination transforms skin cells into iMPCs. They uncovered that while MyoD expression alone drives skin cells to take on the identity of mature muscle cells, the addition of three chemicals causes the skin cells to obtain a more primitive stem cell-like state.

Significantly, iMPCs are molecularly greatly similar to muscle tissue stem cells. Moreover, muscle cells derived from iMPCs are more stable and mature than muscle cells developed with MyoD expression alone.

Mechanistically, we showed that MyoD and the chemicals aid in the removal of certain marks on DNA called DNA methylation. DNA methylation typically maintains the identity of specialized cells, and we showed that its removal is key for acquiring a muscle stem cell identity.”

Masaki Yagi, PhD, Study Lead Author and Research Fellow, Massachusetts General Hospital

Hochedlinger comments that the results may be used in other tissue types other than muscles that involve various regulatory genes. Joining the expression of these genes with the three chemicals utilized in this research could aid scientists to create various stem cell types that closely resemble different tissues in the body.

Source:

Journal reference:

Yagi, M., et al. (2021) Dissecting dual roles of MyoD during lineage conversion to mature myocytes and myogenic stem cells. Genes & Development. doi.org/10.1101/gad.348678.121.