Recent research titled “Diverse transcriptional regulation and functional effects revealed by CRISPR/Cas9-directed epigenetic editing” published in Oncotarget reports that the appropriate functioning of this mechanism is essential for tissue homeostasis and cell fate determination.

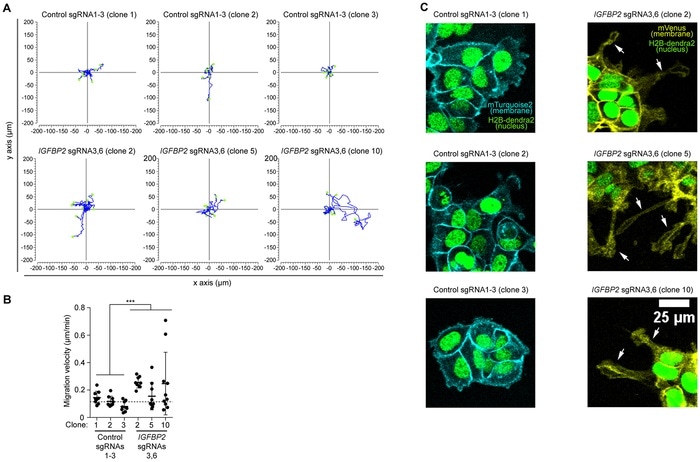

(A) Display of 9 independent migratory tracks from 3 pooled control sgRNAs 1-3 clones and 3 pooled IGFBP2 sgRNAs 3 and 6 clones. (B) Distribution of migration velocity from 3 pooled control sgRNAs 1-3 clones and 3 pooled IGFBP2 sgRNAs 3 and 6 clones. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3–9 independent positions. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for speed and displacement and the T-test for mitotic cell division analysis. p values ≤ 0.05, ≤ 0.01, or ≤ 0.001 are considered statistically significant and indicated by an asterisk (*, **, or ***, respectively). (C) Representative time-lapse images of 3 pooled control sgRNAs 1-3 clones and 3 pooled IGFBP2 sgRNAs 3 and 6 clones. White arrow indicates the appearance of cell protrusions (absent in the control conditions). Images show nuclear marker (H2B-dendra2) to follow cell divisions and migration and membrane markers (mTurquoise-2 and mVenus) to study cell morphology. Image Credit: Miguel Vizoso and Jacco van Rheenen.

In the current research, scientists took advantage of CRISPR/dCas9 technology suited for epigenetic editing through site-specific targeting of DNA methylation. They utilized it to characterize the transcriptional changes of the candidate gene and the functional effects on cell fate in various tumor settings.

Remarkably, this modification resulted in opposing expression profiles of the selected gene in various cancer cell models and impacted the expression of mesenchymal genes CDH1, VIM1, TGFB1, and apoptotic marker BCL2. Furthermore, methylation-induced changes in expression profiles were also followed by a phenotypic switch in cell migration and cell morphology.

“Increasing number of studies report that proteins do not work in isolation but are part of a complex network of biomolecules, that may differ at various settings (e.g., different tumor types [1, 2] or stages of tumor progression,” stated Dr Miguel Vizoso and Dr Jacco van Rheenen.

There are numerous examples of genes with opposing roles. DNA methylation might be one of those triggers of these opposing roles. For instance, the same DNA methylation mark could result in very different outcomes based on the allele tagged with this modification. The researchers analyzed if the same epigenetic modification can also organize molecular and phenotypic diversity in non-imprinted genes.

In the current research, the scientists concentrated on the insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2, a newly identified multitasked gene controlled by DNA methylation which is also reported to play a role both as a tumor-inducing and tumor-suppressing gene.

The different phenotypes when following single alterations in cancer driver genes might simply contemplate the different roles of these genes in separate signaling pathways; however, it might be also due to the differential gene expression patterns of these genes.

DNA methylation constitutes a vital process involved in transcriptomic regulation depending on the occupancy of CpG dinucleotides by 5′-methylcytosine chemical groups.

However, it is still not known if the consequence of DNA methylation on the expression of the target genes and cell fate is uniform irrespective of the cell type or can urge opposing phenotypes based on the tumor cell context. The lack of technologies to target DNA methylation in situ resulted in this remaining elusive for numerous years.

“Our study highlights the significance of exploring the effects of the epigenetic editing in different tumor settings by revealing the important consequences that this can have on transcriptomic regulation and tumor cell behavior,” remark Vizoso/van Rheenen on their Oncotarget research output.

Source:

Journal reference:

Vizoso, M & van Rheenen, J (2021) Diverse transcriptional regulation and functional effects revealed by CRISPR/Cas9-directed epigenetic editing. Oncotarget. doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.28037.