The human immune system works hard to maintain an individual’s health and protect against viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungi, and cancerous cells. When the immune system is weakened, there is a risk for dangerous infections and illnesses and when they are overactive, there occurs the risk for autoimmune diseases and inflammation. Hence precise monitoring of the activity of the immune systems is significant for health.

Immune system illustration. Image Credit: Ilana Fox-Fisher/ Hebrew University of Jerusalem

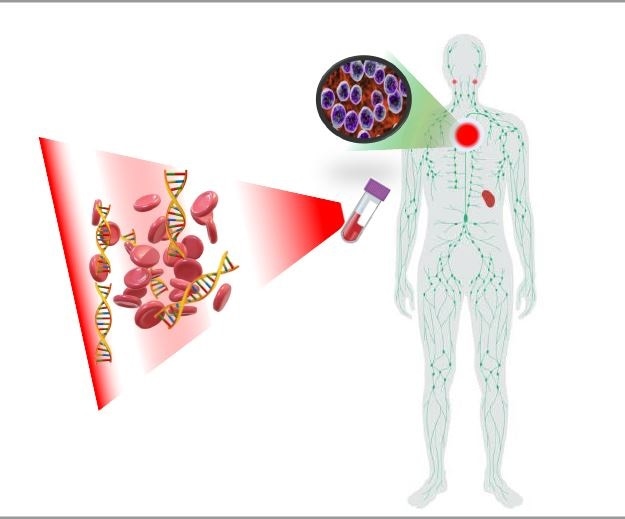

At present, the key means to analyze the immune system’s health is through a blood test that counts immune (white blood) cells. When the number of white blood cells is greater than normal it indicates the presence of an infection in the body that the immune system is combating.

But these blood tests probably fail to apprehend the immune system activity in the remote tissues of the body like those seen in lymph nodes, bone marrow, and other organs. In such cases, the patients should follow up with invasive measures like biopsies and cost-effective and harmful imaging approaches like MRIs and PET/CT scans. However, these advanced testing do not always detect the problem.

Recently a team of researchers headed by Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) MD/PhD student Ilana Fox-Fisher and Professor Yuval Dor at HU’s Institute for Medical Research-Israel Canada (IMRIC) devised a new technique to monitor remote immune mechanisms within those remote organs and tissues.

The research depends on two basic biological principles—cells that are deceased release fragments of DNA into the bloodstream and the DNA of every cell type contains a unique chemical pattern known as methylation. The study was published in the eLife journal.

On the basis of these principles, researchers could pinpoint the tissue from which the circulating fragments of DNA originated and deduce disease states. For instance, a patient fighting breast cancer will have elevated DNA fragments (deposited into the bloodstream after cell death) from breast cells and carry the methylation characteristics of breast cells, likewise cardiac DNA fragments during heart attacks.

These methylation markers allow us to monitor human immune cell dynamics, and provide important information that isn’t accessible in standard blood cell counts. This novel tool can illuminate healthy and pathologic immune processes taking place deep within tissues, which are not accessible at present.”

Yuval Dor, Professor, Institute for Medical Research-Israel Canada, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The scientists as part of their research pinpointed the specific DNA methylation patterns among inflammatory and immune cells types. This enabled them to identify DNA fragments deposited into the bloodstream when immune cells died.

A key finding is that immune-derived DNA fragments are not a simple reflection of circulating blood cells, but rather an accurate report of immune processes happening in the body. Our research suggests that, in principle, doctors could monitor remote but critical immune processes by measuring the immune battle’s casualties, that is, immune-derived DNA fragments circulating in patients’ blood.”

Ilana Fox-Fisher, Institute for Medical Research-Israel Canada, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The scientists analyzed their theory and discovered proof of concept by testing numerous medical conditions where the immune system is activated but standard blood cell counts are normal. The initial analysis was with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), a chronic allergic disease that affects kids and adults and is mostly hard to diagnose.

Until today, EoE diagnoses need invasive endoscopic biopsies as a majority of the patients’ blood counts show normal values. However, Dor’s group identified that the blood of EoE patients’ has abnormally high levels of DNA fragments from eosinophils (determined by their unique DNA methylation pattern).

Our new non-invasive blood test could go a long way in helping diagnosis and monitoring this disease.”

Ilana Fox-Fisher, Institute for Medical Research-Israel Canada, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The researchers also found success with lymphoma, a kind of cancer that generally does not turn up in blood tests. But the novel blood test identifies DNA fragments resulting from the immune system’s fight against lymphoma, without the need for bone marrow aspiration and further imaging.

Fox-Fisher is currently performing an investigation on individuals who were vaccinated against COVID-19 to identify if the levels of DNA released from antibody-producing B-cells increased after vaccination.

Fox-Fisher added, “We’re hopeful this new blood test will give clinicians a more accurate picture of the state of their patient’s health, beyond the standard blood counts which often do not tell the whole story and frequently necessitate invasive follow-up tests and biopsies.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Fox-Fisher, I., et al. (2021) Remote immune processes revealed by immune-derived circulating cell-free DNA. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.70520.