The ability of the human immune system to fight COVID-19, like any infection, is primarily dependent on its ability to multiply immune cells capable of eliminating the disease-causing SARS-CoV-2 virus. These cloned immune cells cannot be generated indefinitely, and a recent University of Washington study suggests that the body’s ability to produce these cloned cells declines considerably with age.

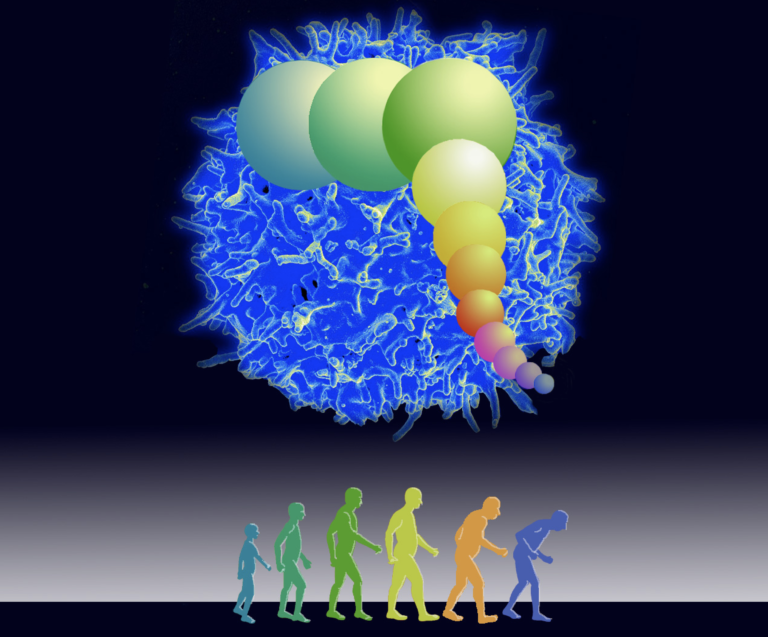

This illustration represents the core theory in a new modeling study led by the University of Washington: The circles represent the immune system’s aging, in which its ability to make new immunity cells remains constant until a person (represented by the human figures) reaches middle-age or older and then falls off significantly. The central blue figure represents an immune system T cell that attacks the virus. Image Credit: Michele Kellett and James Anderson/University of Washington.

This illustration represents the core theory in a new modeling study led by the University of Washington: The circles represent the immune system’s aging, in which its ability to make new immunity cells remains constant until a person (represented by the human figures) reaches middle-age or older and then falls off significantly. The central blue figure represents an immune system T cell that attacks the virus. Image Credit: Michele Kellett and James Anderson/University of Washington.

This genetically programmed limit on the immune system, according to a model developed by UW research professor James Anderson, maybe the answer to why COVID-19 has such a catastrophic effect on the elderly. Anderson is the primary author of an article showing this modeled relationship between aging, COVID-19, and mortality that was published in The Lancet eBioMedicine on March 31th, 2022.

When DNA split in cell division, the end cap—called a telomere—gets a little shorter with each division. After a series of replications of a cell, it gets too short and stops further division. Not all cells or all animals have this limit, but immune cells in humans have this cell life.”

James Anderson, Professor and Modeler of Biological Systems, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington

Despite this restriction, the average person’s immune system performs well until they reach the age of 50. This occurs when enough core immune cells, known as T cells, have shorter telomeres and are unable to clone themselves in large enough quantities through cellular division to attack and remove the COVID-19 virus, which has the property of significantly lowering immune cell numbers, Anderson said.

Telomere lengths, Anderson stressed, are inherited from the parents. As a result, there are some variances in these lengths across persons of all ages, as well as the age at which these lengths are primarily used up.

The “most exciting” conclusion of Anderson’s study is the gap between this theory of aging, which has a cutoff for when the immune system has run out of collective telomere length, and the assumption that humans all age uniformly throughout time.

Depending on your parents and very little on how you live, your longevity or, as our paper claims, your response to COVID-19 is a function of who you were when you were born, which is kind of a big deal.”

James Anderson, Professor and Modeler of Biological Systems, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington

The researchers used publicly accessible data on COVID-19 mortality from the Centers for Disease Control and the US Census Bureau, as well as telomere studies, many of which were reported by the co-authors during the last two decades, to create this model.

Anderson said that gathering telomere length data on a person or a certain population may benefit doctors in determining who was more affected. Researchers might then prioritize resources, like booster doses, based on which populations and individuals are more sensitive to COVID-19.

I’m a modeler and see things through mathematical equations that I am interpreting by working with biologists, but the biologists need to look at the information through the model to guide their research questions. The dream of a modeler is to be able to actually influence the great biologists into thinking like modelers. That’s more difficult.”

James Anderson, Professor and Modeler of Biological Systems, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington

Anderson’s concern with this model is that it may explain too much.

“There’s a lot of data supporting every parameter of the model and there is a nice logical train of thought for how you get from the data to the model. But it is so simple and so intuitively appealing that we should be suspicious of it too. As a scientist, my hope is that we begin to understand further the immune system and population responses as a part of natural selection,” Anderson concluded of the model’s power.

Source:

Journal reference:

Anderson, J. J., et al. (2022) Telomere-length dependent T-cell clonal expansion: A model linking ageing to COVID-19 T-cell lymphopenia and mortality. The Lancet eBioMedicine. doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103978.