Researchers at UT Southwestern have uncovered a molecular path that allows cells to detect when their lipid supplies are running low, triggering a flurry of activity that avoids starvation. The discoveries, which were published in Nature, might lead to novel treatments for metabolic diseases and a number of other diseases in the future.

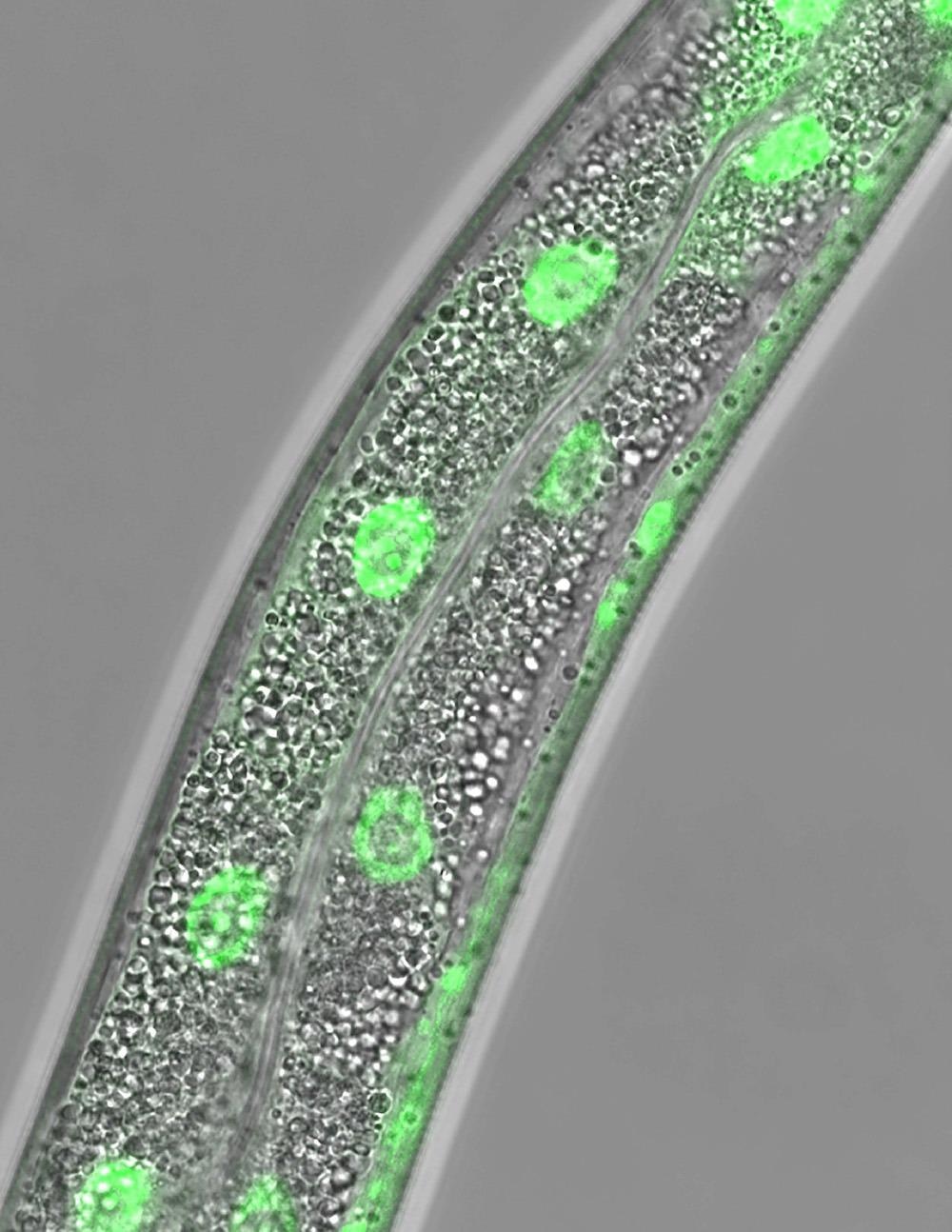

Micrograph of the soil-dwelling worm, C. elegans, shows the cellular location of the fluorescent protein, nuclear hormone receptor 49 or NHR-49. Adult animals have been deprived of food for 24 hours, which promotes the accumulation of NHR-49 within the nuclei of intestinal cells of the worm. Image Credit: UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Micrograph of the soil-dwelling worm, C. elegans, shows the cellular location of the fluorescent protein, nuclear hormone receptor 49 or NHR-49. Adult animals have been deprived of food for 24 hours, which promotes the accumulation of NHR-49 within the nuclei of intestinal cells of the worm. Image Credit: UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Lipids are critical for supplying energy and serving as components for membranes and other cellular structures. The mechanism we discovered appears to be a way for cells to universally gauge lipid levels without having to distinguish between the vast variety of different lipid types.”

Dr Peter Douglas, PhD, Study Leader and Assistant Professor, Molecular Biology, University of Texas Southwestern

Dr Douglas, a member of UT Southwestern’s Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine, noted that mammalian cells contain tens of thousands of chemically unique lipids, a class of molecules made up of hydrocarbon chains that are the body’s most energy-rich compounds.

The SREBP pathway, which helps cells control cholesterol levels by detecting a kind of lipid called sterols, was discovered in the 1990s by UT Southwestern Nobel Laureates Michael Brown, MD as well as Joseph Goldstein, MD, both being Professors of Molecular Genetics and Internal Medicine.

This is accomplished by SREBP pathway components directly binding sterol molecules. Dr Douglas believes that extra sensing systems exist in the cell to accommodate a large number of distinct lipid types.

The researchers deprived Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm species that acts as a popular lab model and shares many genes with humans, in order to find a method that cells may use to sense lipid levels in general.

When these animals were starved for 24 hours, the researchers discovered that a protein called nuclear hormone receptor 49 (NHR-49) migrated from the cytosol—the liquid component of cells—to the nucleus, where it triggered a cascade of gene activity that prompted the transport of other proteins to the cell surface to collect extracellular nutrients.

The researchers discovered that when C. elegans were well-nourished, a protein called RAB-11.1 kept NHR-49 in place. The late Alfred G. Gilman, MD, PhD, a Nobel Laureate and longstanding Chair of Pharmacology at UTSW who also worked as Dean of the Medical School, Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, and Provost, discovered the small G protein family. However, under starvation, RAB-11.1 released NHR-49, allowing it to enter the nuclear reactor.

Further research revealed that the absence of a lipid called geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate causes this release. Because cells can produce geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate from nearly any lipid, its presence acted as a universal signal for optimal lipid levels in cells, Dr Douglas added.

Other laboratories’ previous research has indicated that components of this pathway are involved in a variety of diseases and health concerns, like a metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, viral infections, neurological aging, and certain cancers, Dr Douglas stated.

Dr Douglas believes that manipulating this novel lipid-sensing route might lead to new therapies for these diseases.

Dr Douglas is a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar and a Southwestern Medical Foundation Scholar in Biomedical Research.

Source:

Journal reference:

Watterson, A., et al. (2022) Intracellular lipid surveillance by small G protein geranylgeranylation. Nature. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04729-7.