A virus must go through the viral replication cycle in order to propagate throughout the body and cause disease. The UNC School of Medicine researchers studied that cycle in the hepatitis A virus (HAV) and found that replication necessitates certain interactions between the human protein ZCCHC14 and a family of enzymes termed TENT4 poly(A) polymerases.

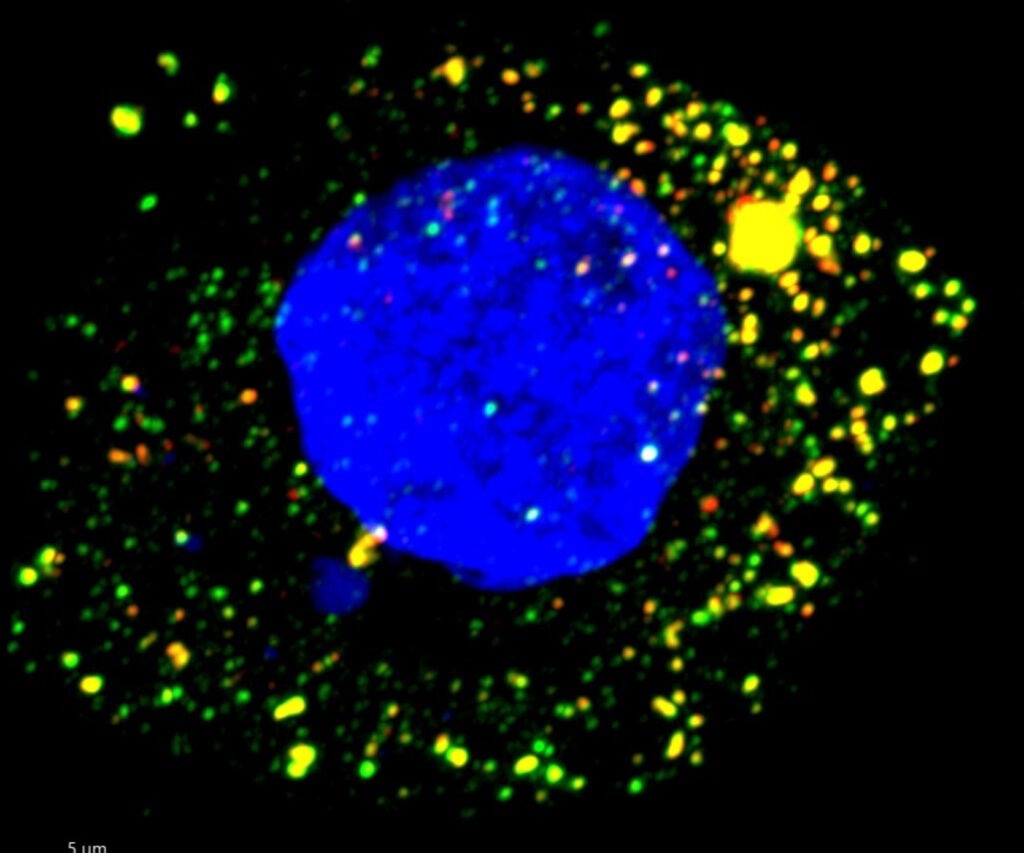

Fluorescence microscopy image of HAV-infected cultured human liver cell. viral RNA targeted by ZCCHC14 appears green, and the virus’s protein red. Image Credit: Maryna Kapustina, PhD.

Fluorescence microscopy image of HAV-infected cultured human liver cell. viral RNA targeted by ZCCHC14 appears green, and the virus’s protein red. Image Credit: Maryna Kapustina, PhD.

Additionally, researchers discovered that the oral drug RG7834 halted viral replication at a critical stage, preventing liver cell infection.

These findings are the first to show that a pharmacological therapy for HAV is successful in an animal model of the disease and were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Our research demonstrates that targeting this protein complex with an orally delivered, small-molecule therapeutic halts viral replication and reverses liver inflammation in a mouse model of hepatitis A, providing proof-of-principle for antiviral therapy and the means to stop the spread of hepatitis A in outbreak settings.”

Stanley M. Lemon, MD, Study Senior Author and Professor, Department of Medicine, Microbiology & Immunology, University of North Carolina Health Care

Lemon also be a member of the UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases.

The first inactivated HAV vaccine to be given to people was produced by a research team at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in the 1970s and 1980s, according to Lemon. After the vaccine was widely available in the mid-1990s, research on HAV slowed down. As vaccination rates soared in the 2000s, the number of cases decreased. The hepatitis B and C viruses, which differ greatly from HAV and also cause chronic disease, caught the interest of researchers.

“It’s like comparing apples to turnips. The only similarity is that they all cause inflammation of the liver,” Lemon stated. Hepatitis B and C viruses are not even members of the same viral family as HAV.

Despite the high efficacy of the HAV vaccination, hepatitis A outbreaks have increased since 2016. Lemon emphasized that not everyone receives vaccinations and that HAV can persist for a very long time in the environment, including on the hands, in food, and in water. Since 2016, the CDC reports that there have been more than 44,000 cases, 27,000 hospitalizations, and 400 fatalities in the United States.

Over the past few years, there have been a number of outbreaks, including one that killed 20 people and sickened 600 people in San Diego in 2017. This outbreak was mostly caused by homelessness and drug use. A minor outbreak associated with organic strawberries occurred in many states in 2022 and resulted in roughly a dozen hospitalizations.

In 2019, fresh blackberries were related to yet another epidemic. Tens of millions of HAV infections are placed annually around the world. Fever, stomach ache, jaundice, nausea, as well as loss of taste and appetite, are some of the symptoms. Once diseased, there is no cure.

Lemon and colleagues revealed in 2013 that the hepatitis A virus undergoes significant modifications within the human liver. As it exits liver cells, the virus targets bits of the cell membrane to disguise itself from antibodies that may have otherwise contained it before it spread far in the bloodstream.

This research, which was published in Nature, revealed how much is still unknown about the virus that was first identified 50 years ago and is thought to have been the source of disease as far back as ancient times.

A few years ago, scientists discovered that the hepatitis B virus needed TENT4A/B to replicate. In the meanwhile, tests conducted in Lemon’s lab identified ZCCHC14, a specific protein that interacts with zinc and binds to RNA, as being required by humans for HAV to reproduce.

This was the tipping point for this current study. We found ZCCHC14 binds very specifically to a certain part of HAV’s RNA, the molecule that contains the virus’s genetic information. And as a result of that binding, the virus is able to recruit TENT4 from the human cell.”

Stanley M. Lemon, MD, Study Senior Author and Professor, Department of Medicine, Microbiology & Immunology, University of North Carolina Health Care

TENT4 participates in an RNA modification pathway during cell growth in typical human biology. TENT4 is essentially taken over by HAV, which then utilizes it to reproduce its own genome.

According to this research, preventing TENT4 recruitment might prevent viral replication and reduce disease. The substance RG7834, which had previously been demonstrated to actively stop the Hepatitis B virus by targeting TENT4, was then put to the test in Lemon’s lab.

In the PNAS article, the researchers provided specific information on how oral RG7834 affects HAV in the liver and feces as well as how the virus’s capacity to produce liver damage is significantly reduced in mice that have been genetically engineered to acquire HAV infection and disease. According to research, the substance was secure at the dose employed in this study and within the immediate time period of the study.

This compound is a long way from human use. But it points the path to an effective way to treat a disease for which we have no treatment at all.”

Stanley M. Lemon, MD, Study Senior Author and Professor, Department of Medicine, Microbiology & Immunology, University of North Carolina Health Care

In a phase 1 study, Hoffmann-La Roche, a pharmaceutical firm, tested RG7834 on people to see whether it may treat chronic hepatitis B infections. However, animal tests indicated that it could be too hazardous for long-term usage.

“The treatment for Hepatitis A would be short term, and, more importantly, our group and others are working on compounds that would hit the same target without toxic effects,” Lemon concluded.