At Uppsala University, a DNA sequence found in jawed vertebrates has been discovered and characterized by scientists. This includes sharks and humans, but it is absent in jawless vertebrates, like lampreys.

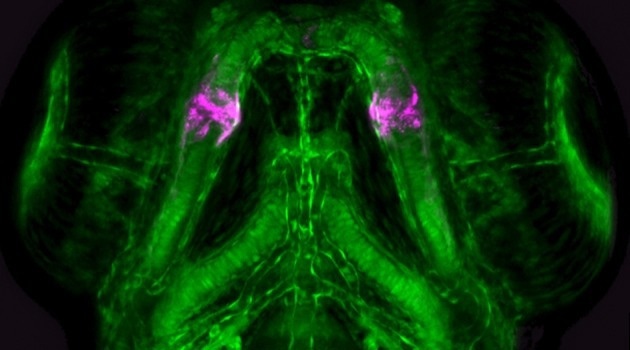

A regulatory DNA sequence preserved in jawed vertebrates labels the jaw joint cells (magenta) on the background of craniofacial cartilages and blood vessels (green) in the head of zebrafish larva. Image Credit: Laura Waldmann

A regulatory DNA sequence preserved in jawed vertebrates labels the jaw joint cells (magenta) on the background of craniofacial cartilages and blood vessels (green) in the head of zebrafish larva. Image Credit: Laura Waldmann

During embryo development, this DNA seems to be the significant factor in shaping the joint surfaces. The great majority of vertebrate species existing today, such as humans, belong to the jawed vertebrate group.

At the time of vertebrate evolution, the development of articulating jaws was known to be one of the most considerable evolutionary transitions that happened from jawless to jawed vertebrates, occurring at least 423 million years ago.

Initially, the lower and upper jaws were related to the primary jaw joint. But at the time of the evolution of mammals, this moved to the middle ear to improve hearing and was substituted by the secondary jaw joint, which is how humans have been constructed at present.

The main jaw joint has been developed at the time of embryonic development and has an activity that consists of sequence data for a particular protein—named transcription factor Nkx3.2.

For a long time, this protein played a significant role in the progress of this jaw joint. However, little was known before regarding how its gene activity is controlled in the jaw joint cells.

Activating genes

Normally, genes have been triggered with the help of DNA sequences, called enhancers, which do not consist of gene sequence information. Moreover, such “regulatory” DNA can add up to the activation of the gene just in a few cell types and could be conserved among various animal species.

We searched through the genome sequences of many different vertebrate species and only found the DNA sequence near the Nkx3.2 gene in jawed vertebrates—not in jawless ones.”

Tatjana Haitina, Study Lead and Researcher, Uppsala University

Haitina added, “When we injected these DNA sequences from jawed vertebrates into zebrafish embryos, they were all activated in the jaw joint cells. The fact that their ability to activate has been preserved for over 400 million years shows how important it is for jawed vertebrates.”

“In experiments where we deleted the newly discovered DNA sequence from the zebrafish genome using the CRISPR/Cas9 technique, we saw that the early activation of the Nkx3.2 gene was reduced, which caused defects in the jaw joint shape. It turned out that these defects were later repaired, suggesting that there is additional regulatory DNA somewhere in the genome that controls the activation of the Nkx3.2 gene and is waiting to be discovered,” added Jake Leyhr, a doctoral student in the research team.

The scientists hope that their breakthrough is a significant step towards ultimately comprehending the process behind the origins of vertebrate jaws.

The study was performed in partnership with SciLifeLab’s Genome Engineering Zebrafish and BioImage Informatics units.

Source:

Journal reference:

Leyhr, J., et al. (2022) A novel cis-regulatory element drives early expression of Nkx3.2 in the gnathostome primary jaw joint. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75749