Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, the CNRS, and the Collège de France researchers have employed paleogenomics to trace 10,000 years of human immune system evolution. They examined the genomes of over 2,800 individuals who lived in Europe over the past 10 millennia.

Explanatory diagram. Image Credit: © Gaspard Kerner, Institut Pasteur

Explanatory diagram. Image Credit: © Gaspard Kerner, Institut Pasteur

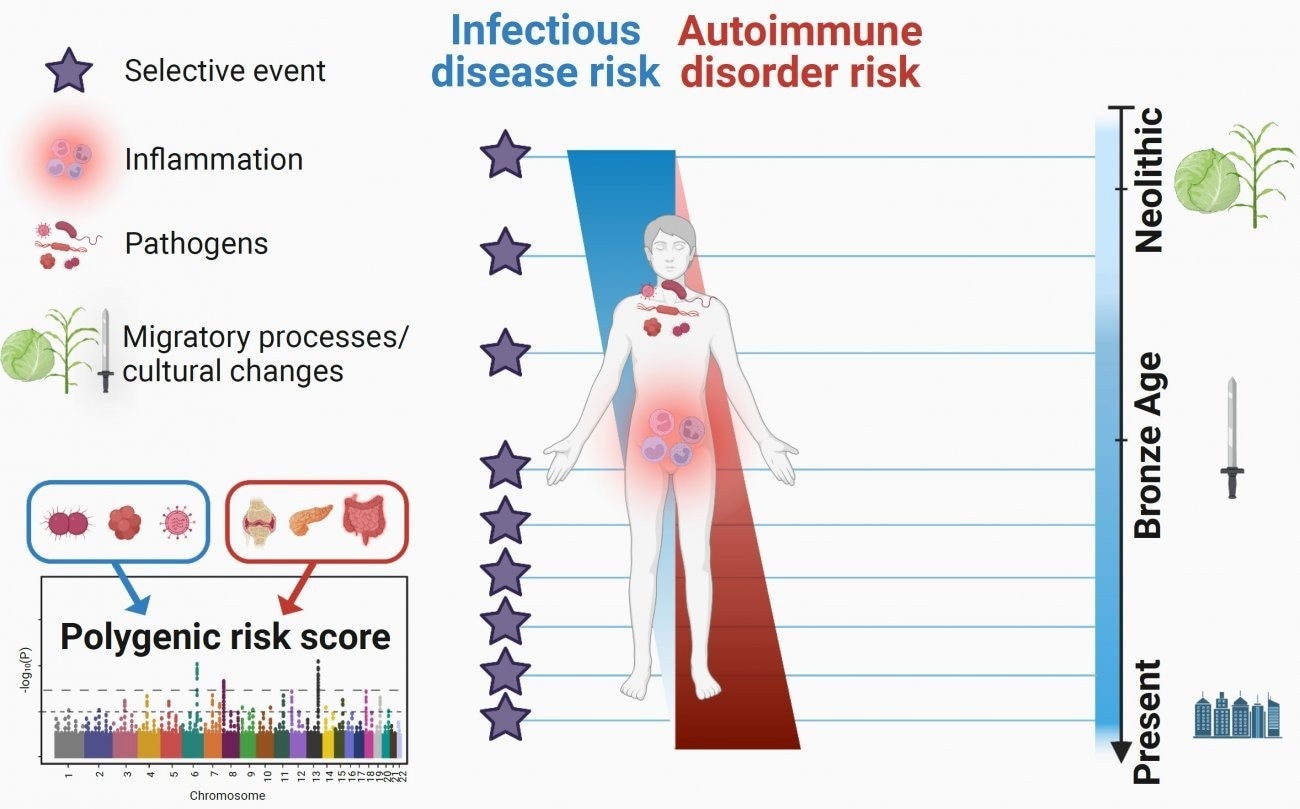

Researchers were able to pinpoint the increase in the frequency of most pathogen-defeating changes after the Bronze Age, approximately 4,500 years ago. The researchers also discovered that mutations that increase the likelihood of acquiring inflammatory disorders have become increasingly common during the last 10,000 years. On January 13th, 2023, these fascinating findings on the impacts of natural selection on immune genes were published in the journal Cell Genomics.

J.B.S. Haldane, a geneticist, associated the maintenance or persistence of the mutation responsible for red blood cell aberrations often reported in Africa in the 1950s with the protection these anomalies gave against malaria, an endemic infection that takes millions of lives.

According to this view, infections are among the most powerful selective forces that humans face. Following that, several population genetics results indicate the notion. But important issues remained, particularly concerning the specific epochs during which the selective pressures imposed by infections on human populations were greatest and their effect on the present-day risk of developing inflammatory or autoimmune disorders.

To resolve these issues, researchers from the Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, CNRS, and Collège de France collaborated with the Imagine Institute and The Rockefeller University (United States) on a paleogenomics approach.

This discipline has resulted in significant discoveries regarding the history and development of humans and human diseases, as evidenced by the decision to give the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo.

The scientists examined the variability of the genomes of over 2,800 individuals who lived in Europe during the last 10 millennia, spanning the Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Middle Ages, and modern times, in research led by the Institut Pasteur and published on January 13th, 2023, in the journal Cell Genomics.

The researchers first identified mutations that quickly increased in frequency in Europe by recreating the evolution of hundreds of thousands of genetic mutations over time, demonstrating that they were helpful. These “positive” natural selection mutations are mostly found in 89 genes that are enriched in functions related to the innate immune response, particularly the OAS genes, which are responsible for antiviral activity, and the gene responsible for the ABO blood group system.

Interestingly, the majority of these positive selection events, which show a genetic adaptation to the pathogenic environment, began very recently, around 4,500 years ago, at the onset of the Bronze Age. The scientists attribute this “acceleration” in adaptation to human population growth during this time period and/or to significant selective pressures applied by pathogens during the Bronze Age, which were most likely linked to the spread of serious infectious diseases like plague.

At the same time, the researchers examined the opposite scenario, that is, mutations whose frequency has decreased dramatically during the last ten millennia. Because they raise the risk of disease, these mutations are most likely susceptible to “negative” selection. They observed that, once again, these selection events began mostly in the Bronze Age.

Many of these harmful mutations were also found in genes related to the innate immune response, such as TYK2, LPB, TLR3, and IL23R, and have been shown in experiments to have a negative influence on infectious disease risk. The findings highlight the importance of using an evolutionary approach in research on genetic susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Furthermore, the researchers investigated the notion that pathogen selection in the past favored genes imparting resistance to infectious diseases, but that same alleles have since raised the likelihood of autoimmune or inflammatory disorders. They looked at the few thousand mutations that have been linked to increased susceptibility to tuberculosis, hepatitis, HIV, or COVID-19, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or inflammatory bowel disease.

Looking at the evolution of these mutations over time, they discovered that those associated with an increased risk of inflammatory disorders, such as Crohn’s disease, became more common over the last 10,000 years, while those linked to a higher risk of developing infectious diseases became less common.

“These results suggest that the risk of inflammatory disorders has increased in Europeans since the Neolithic period because of a positive selection of mutations improving resistance to infectious diseases,” details Lluis Quintana-Murci, director of the study and Head of the Human Evolutionary Genetics Unit (Institut Pasteur/CNRS Evolutionary Genomics, Modeling, and Health Unit/Université Paris Cité).

The study’s findings, which drew on the vast potential of paleogenomics, show that natural selection has targeted human immunity genes in Europe over the last ten millennia, particularly since the beginning of the Bronze Age, contributing to current disparities in the risk of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Source:

Journal reference:

Kerner, G., et al. (2023) Genetic adaptation to pathogens and increased risk of inflammatory disorders in post-Neolithic Europe. Cell Genomics. doi.org/10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100248.